Published September 2025 as part of the proceedings of the first Alpaca conference on Algorithmic Patterns in the Creative Arts, according to the Creative Commons Attribution license. Copyright remains with the authors.

doi:10.5281/zenodo.17084380

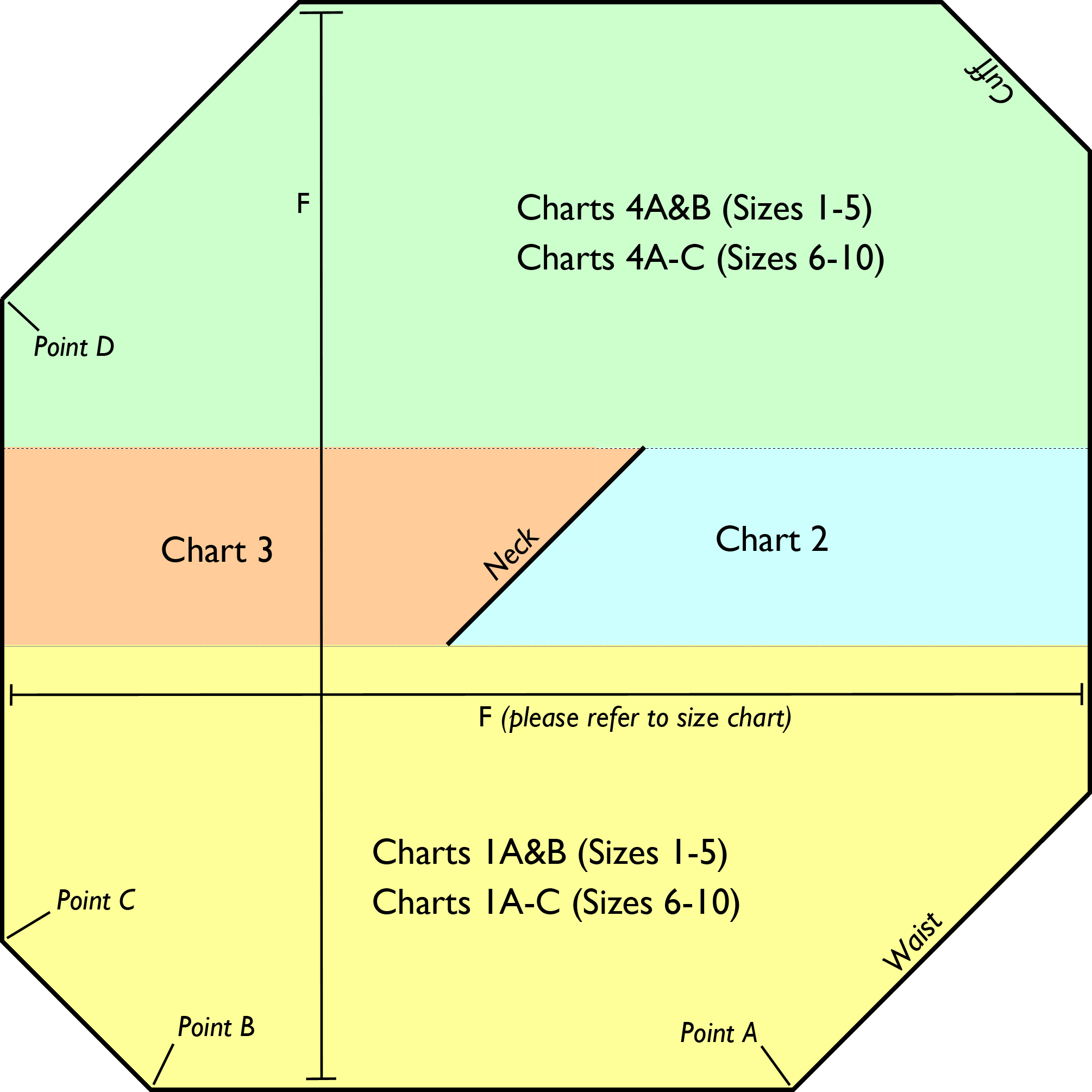

Algorithmic Knitting Design 1 is a long-term project initiated in 2020 by composer, interdisciplinary maker, designer and voice artist Stephanie Pan 2 integrating fashion design, knitting, and algorithmic computing. Through this project Stephanie develops knitting patterns for apparel and (home) accessories for handknitters, incorporating digital aesthetics into their texture patterns. Alongside Stephanie, the team includes composer/interdisciplinary artist/researcher Stelios Manousakis, PhD 3, composer/software developer Jan Trützschler von Falkenstein, PhD 4, and computational architect Weihaw Wang, founder of Sawara Architects. 5 There are currently 10 published patterns available. Approximately 3-4 patterns are published per year, with the intention to continue this work and further develop the project.

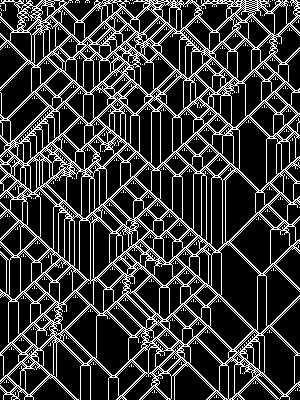

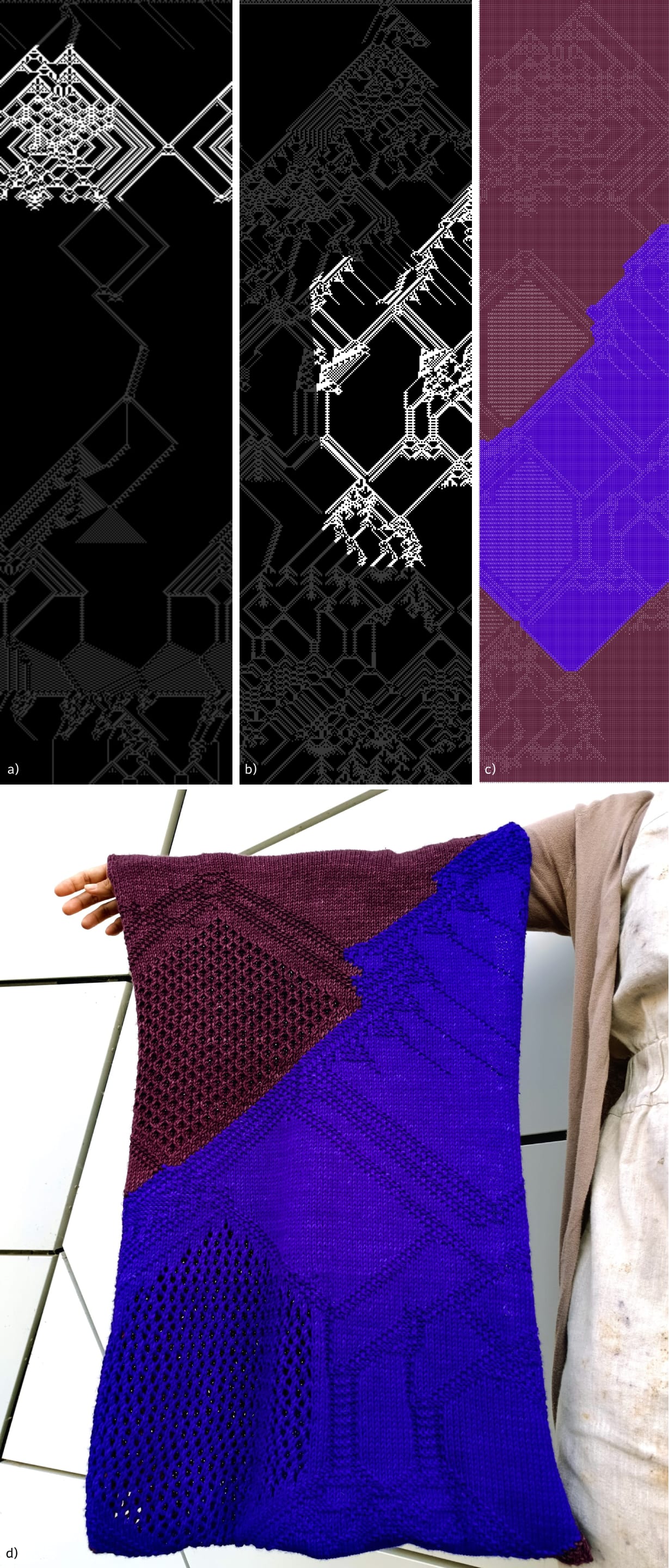

The design process involves translating algorithms into various knitting techniques such as knit-and-purl textures, fairisle colorwork, intarsia, a new version of ‘marlisle’ 6 developed by Stephanie, and lacework, with further research into cable textures. So far, designs have focused on Cellular Automata (CA) as a means for generating texture and colorwork patterns. As Holden and Holden (2021, 443) note, owing to the grid-based nature of this algorithm, “many fiber arts provide natural ways of depicting cellular automata”. 7

Algorithmic Knitting Design seeks to: a) present traditional handicrafts, and specifically knitting, as applied science and mathematics; b) take a major step in updating the aesthetics, sensibilities and possibilities of hand-knitting through digital technology; c) democratize and extend the boundaries of ‘high art’ by offering artistic blueprints as accessible knitting patterns to a broad, vast and varied audience typically different from a contemporary art audience. This approach, i.e. providing the instructions for others to create an artwork, is similar to Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings. 8

Knitting has remained a vital, relevant handicraft and tool through over 3 millennia. Requiring only access to yarn/string and knitting needles, knitting combines portability with practicality, as well as being a pleasurable and soothing manner to clothe and protect oneself from the elements (once adequate proficiency has been achieved). Continuing to help evolve this practice is essential to enduringly recontextualize an age-old craft, with millions of current practitioners worldwide, in current reality. The project centers the knitter in its approach and takes their perspective as a starting point in its priorities.

Knitting patterns can be thought of in similar terms to computer code - more specifically, low-level assembly language - as written instructions that can be read to produce a specified outcome. Textile design and computation are intrinsically connected through a shared genealogy, exemplified by punchcard technology developed by Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1803 to control the Jacquard Loom. Punchcards were adopted by Charles Babbage in 1837 as a mechanism for storing data and math operations for his Analytical Engine and used subsequently by Ada Lovelace in 1843 to create the first computer program - a methodology that remained fundamental to computing until the 1960s. 9 While this connection may be clear within scientific and research communities, it is generally forgotten or even unknown to general public and the crafting community at large. Algorithmic Knitting Design aims to revisit and revive this link between computing and fiber arts, examining how computational advances - and in particular algorithmic thinking - can help us redefine the traditional art of knitting within a contemporary aesthetic.

Recently, there has been a growing interest by scientists and researchers in exploring how knitting can inform scientific research. Janelle Shane’s experiments with Machine Learning 10 and the research of mathematician and physicist Dr. Elisabetta Matsumoto and her colleagues at Georgia Tech 11 12 13 are examples of research through knitting design, investigating how old applied knowledge can inform and evolve new knowledge and theoretical thinking.

Within the realm of fashion and wearable design, a number of fashion designers are integrating new technologies into their work, most notably Iris van Herpen. 14 Knitwear is an inherent part of the commercial fashion design sector, and there are many designers using digital design techniques for knitwear within their collections. Independent specialists in knitwear include Fabienne Serriere and her CA design work as KnitYak 15, and Sebastian Kox aka monobrau’s glitchwear. 16 Tech-driven experiments in knitwear are almost exclusively limited to machine knitting that allow for high levels of intricacy, complexity, automation, and rapid fabrication. In practically all such cases, the product is fully fabricated and the patterns are not available. This creates a closed proprietary loop concealing the blueprint of the design - an understandable approach given both the commercial nature of the industry and the complexity involved in computational design.

In textile art applications, it is fairly common practice for large scale textile works to include community contributions and shared creation by and with crafting communities, and are often part of a communal feminist practice. This is also true in more tech-driven instances, e.g. Margaret Wertheim’s Coral Reef Project 17, Pei Ying Lin’s Studies of Interbeing – Trance 1.1 – Knit a Spike Protein 18. The resulting work of the crafters ultimately belong to the artwork, with patterns shared with individuals being parts of a whole, rather than a standalone piece.

Access to available contemporary, digital design patterns for self-fabrication for the handcrafter is severely lacking, with limited offerings to computational, digital approaches. One such example is atacac’s Sharewear platform which contains downloadable sewing patterns generated with 3D modelling and similar digital tools. 19 20. In the last 25 years, a handful of knitwear designers and researchers have been investigating the utilization of CA to create publicly available handknitting patterns. Of note are Debbie New’s designs, likely the first published applications of CA in knitting 21 22, a shawl pattern by well-established knitwear designer Norah Gaughan 23, and designs by Lana Holden based on a special type of CA she developed for knitting. 24 25 However, these applications remain limited in scope.

In contrast to the closed loop of fashion, Algorithmic Knitting Design develops knittable patterns with high fashion aesthetics that are publicly accessible to all knitters. Designs are inspired by the Belgian and Japanese minimalist approach to form and construction, and by digital aesthetics for texture and colorwork patterns. The project opens up the field of handknitting through technology and offers a new proposal for evolving it, allowing knitters to become active participants in executing / fabricating algorithmic designs with a contemporary aesthetic, without requiring them to know how to code. The project taps into a field of traditional arts with built-in crossover potential to algorithmic thinking and skilled practitioners who have the ability to understand, interpret and execute complex forms and patterns.

Approaching this project with the feminist concept ‘the personal is

political’ 26, the need to bring these two worlds

together, algorithms and knitting, comes from two major

motivations:

* The desire to challenge notions and understandings of what is

‘scientific’ or ‘technological’ versus what is not, and specifically to

posit knitting as a form of applied science from the perspective of the

knitter, as opposed to an academic approach. * A personal desire to wear

and create complex and challenging knit apparel that is contemporary and

takes into account digital aesthetics.

Algorithmic Knitting Design approaches the integration of technology and handicraft as research for design: a craft-centric examination of what science can mean to traditional craft. It aims to contribute to the two-way discourse between algorithmic thinking and knitting from this antithetical point of view that emerges from the perspective of the knitter, rather than of the scientist.

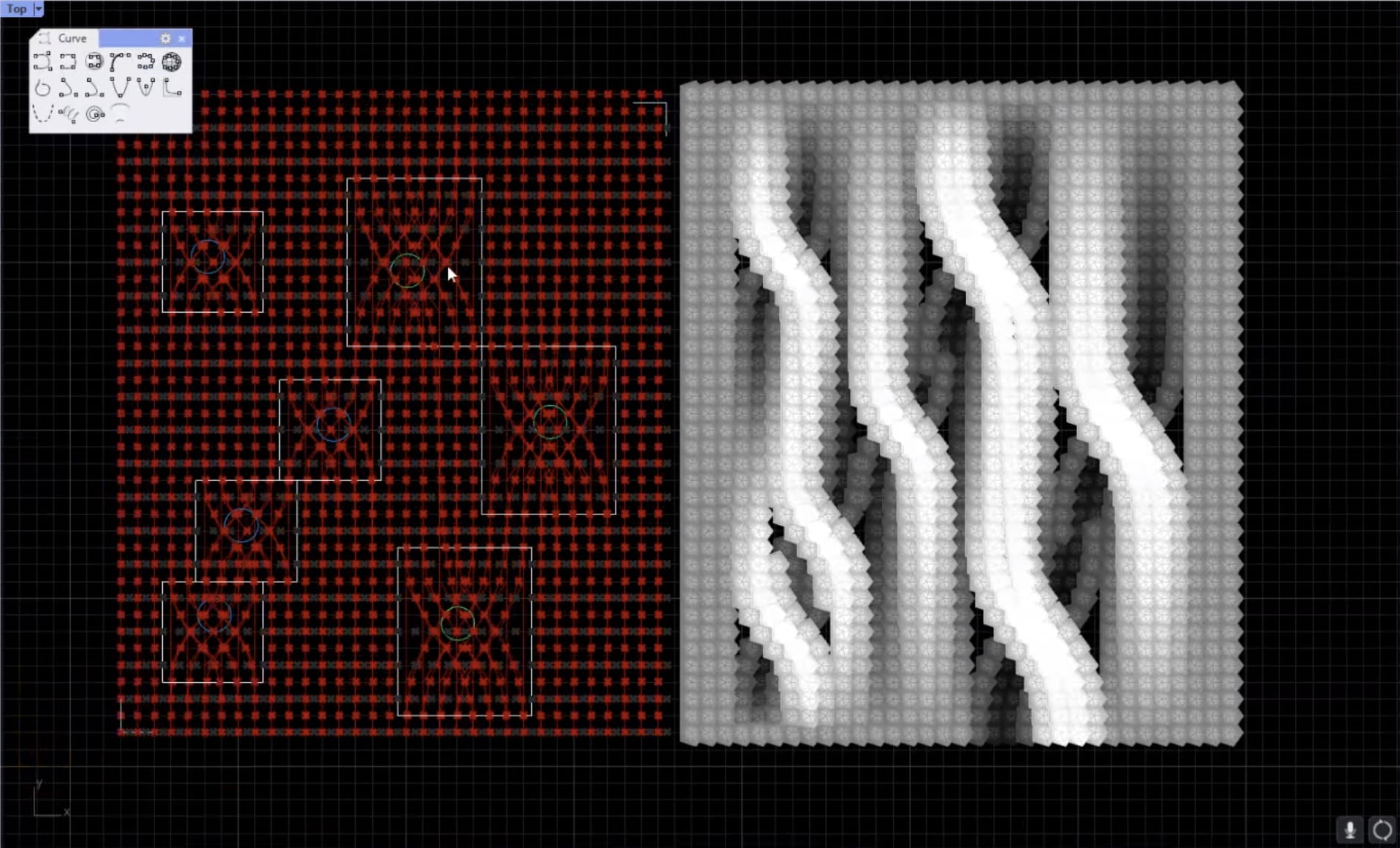

Stephanie and Stelios initially established a workflow for designing knitwear and developing knitting patterns based on open source software for algorithmic design, in conjunction with knitwear designing software Stitch Fiddle. 27 Proof-of-concept tests involved Mirek Wojtowicz’s Cellular Automata simulator Mirek’s Celebration, or MCell. 28 This was soon replaced by Stelios’ development of a Cellular Automata parametric and algorithmic design environment in the SuperCollider programming language 29, using Yota Morimoto’s port of Wojtowicz’s CA code. 30 31 The process has further been streamlined by Jan’s conversion of Stelios’s implementation into a standalone app, Knitting Factory. 32 This enables Stephanie to design autonomously using this app together with Stitch Fiddle.

The knitting design process currently involves the following steps.

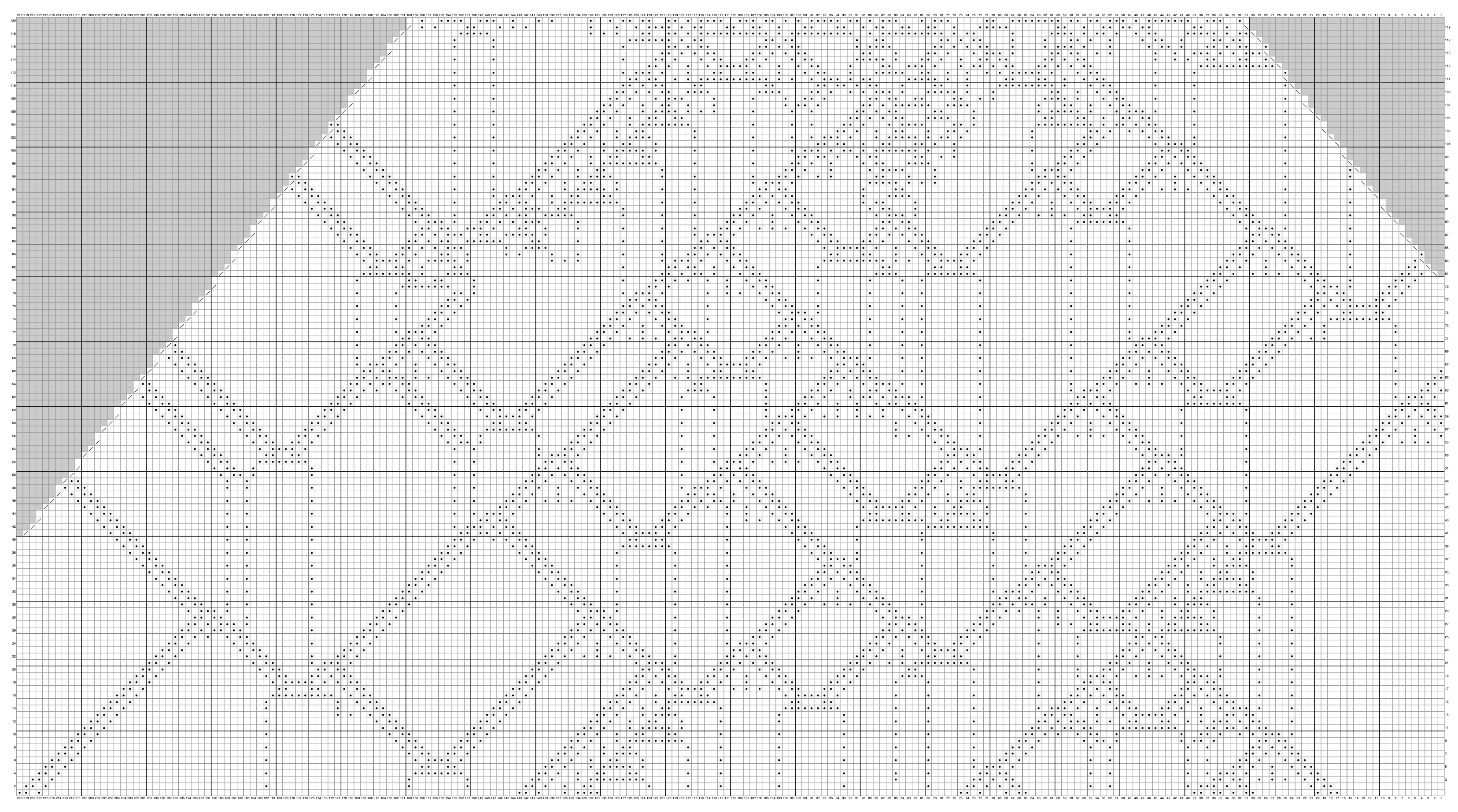

The binary nature of the 1-D cellular automata algorithms we have been focusing on so far have some limitations: Their output lends itself very well to knitting techniques that are similarly binary in nature— knit-and-purl textures, fairisle colorwork, intarsia and to a certain extent, marlisle. Different CA rules lend themselves better to different techniques. Iterations with large swaths of 0’s translate well to knit-and-purl textures, intarsia, and marlisle, but are problematic for fairisle, requiring long chains of ‘catching floats’. 37 Vertical lines must be adjusted to appear correctly in knit-and-purl textures. 38 Highly chaotic textures generally translate best in fairisle colorwork.

However, when translating to non-binary knitting techniques, such as lacework and cable textures, much more creative, manual and labor-intensive interpretation of the CA output is necessary. CA lacework requires manually translating the image file in Stitch Fiddle cell-by-cell and stitch-by-stitch requiring at a minimum 3 types of stitches (of which 2 are interdependent), and more realistically at least 7 different types of stitches (5 of which are interdependent). Charts run between approximately 60-200 stitches per row times 100-400 rows in total, or upwards of 80,000 stitches, depending on the item (lower end is for smaller cowls, higher end is for largest sizes of garments). The other challenge with lacework is that it is fairly unpredictable and the charts are not very indicative of the knitted result, and thus require much more prototyping (i.e. handknitting samples/swatches) which is labor-intensive and time consuming.

For all knitting techniques, there is the overarching challenge of balancing complexity with executability and enjoyment. Finding ways to incorporate sections of ‘mindless knitting’, i.e. repeating patterns such as stockinette, moss stitch, rib stitch, etc. into the patterns are generally good ways to increase executability and balance required focus and practical portability, as charts are generally very large, and generally most readable when printed.

Current research with Stelios includes exploring L-systems for generating lacework, but still ultimately runs into similar challenges as cellular automata. The largest challenges are: developing an algorithm that can account for the interdependency of lace stitches, and still output something visually aesthetic; the time- and labor- intensive nature of prototyping in handknitting; outputting a readable chart for publication – Stitch Fiddle is only equipped to translate images into colorwork knitting charts, not interpret symbols from imported files. While this is easy enough to manage when translating the chart for knit-and-purl textures as well as intarsia, the workflow breaks down for more complex techniques such as lacework and cables. Research into cable textures is being done with Weihaw, developing a visualization software for designing with cables. Similar to lacework, cable knitting charts offer little insight into the actual end result of the knitted fabric. Weihaw’s software will allow for visual placement of cables, after which point it will output a knittable chart with the appropriate cable stitches and world sizes. Further future plans include a potential residency at the Making With… cluster of the Department of Industrial Design at TU Eindhoven 39, through Dr. Kristina Andersen, where they have a textile lab, including a Kniterate digital knitting machine, which would make prototyping and experimenting with techniques much more efficient.

The project ultimately aims to take a major step in updating current expectations and aesthetics in the knitting community by challenging knitters’ understanding of their own craft. It balances contemporary high fashion aesthetics with practicality and wearability, and large, non-repeating patterns with executability. Algorithmic Knitting Design asks an open-ended question: if we start to understand ourselves, knitters, as scientists, as extraordinary physical computers, what happens to our approach to the craft, our ideas on what we can do and accomplish, and what new challenges can we take on?

https://algorithmicknitting.com/↩︎

https://stephaniepan.com/↩︎

https://modularbrains.net/↩︎

https://falkenst.com/↩︎

https://www.sawara.co.uk/↩︎

Marlisle is a new technique developed and coined by Anna Maltz that allows for colorwork worked both flat and in the round.↩︎

Holden, Joshua, and Lana Holden. “A survey of cellular automata in fiber arts.” Handbook of the Mathematics of the Arts and Sciences (2021): 443-465.↩︎

See examples of LeWitt’s Wall Drawings here: https://massmoca.org/sol-lewitt/↩︎

Harlizius-Klück, Ellen. “Weaving as binary art and the algebra of patterns.” Textile 15, no. 2 (2017): 176-19↩︎

Thompson, Clive. “Skyknit: Knitting Patterns Produced by a Neural Net.” Boing Boing, March 12 (2018). https://boingboing.net/2018/03/12/skyknit-knitting-patterns.html.↩︎

Roberts, Siobhan. “‘Knitting Is Coding’ and Yarn Is Programmable in This Physics Lab.” New York Times, May 17 (2019). https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/17/science/math-physics-knitting-matsumoto.html.↩︎

Markande, Shashank G., and Elisabetta A. Matsumoto. “Knotty knits are tangles on tori.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.01497 (2020).↩︎

Singal, Krishma, Michael S. Dimitriyev, Sarah E. Gonzalez, A. Patrick Cachine, Sam Quinn, and Elisabetta A. Matsumoto. “Programming mechanics in knitted materials, stitch by stitch.” Nature Communications 15, no. 1 (2024): 2622.↩︎

https://www.irisvanherpen.com/↩︎

https://web.archive.org/web/20211001154947/http://knityak.com/↩︎

https://monobrau.com/↩︎

Wertheim, Margaret. “Corals, crochet and the cosmos: how hyperbolic geometry pervades the universe.” The Conversation. January 27 (2016).↩︎

https://soitrance.peiyinglin.net/knittogether/↩︎

https://shop.atacac.com/collections/sharewear↩︎

https://www.insider-trends.com/why-does-swedish-clothing-brand-atacac-give-its-patterns-away-for-free/↩︎

New, Debbie. “Celluar automaton knitting.” Knitter’s Mag 49 (1997): 82-83.↩︎

New, Debbie. “Unexpected knitting”. Schoolhouse Press, Stevens Point, 2003.↩︎

Gaughan, Norah. Knitting nature: 39 designs inspired by patterns in nature. Abrams, 2021.↩︎

Holden, Lana. “Knit Stranded Cellular Automata.” Sockupied, no. 10 (Spring 2014).↩︎

Holden, Lana. “Automata Socks.” Sockupied, no. 11 (Spring 2014).↩︎

‘The personal is political’ is a phrase first popularized in second wave feminism in the late 1960s. It asserts that everyday struggles traditionally regarded as private or trivial within patriarchal structures (dissatisfaction with family values, nuclear families, women as homemakers) are systemic and structural and as such must be addressed more broadly than within the private realm. The phrase was popularized by the publication of feminist activist Carol Hanisch’s 1969 essay, “The Personal Is Political.”↩︎

https://www.stitchfiddle.com/↩︎

The software was recently updated into a web application that can be found here: https://mcell.ca/↩︎

https://scsynth.org/↩︎

Morimoto, Yota. “Hacking cellular automata: an approach to sound synthesis.” In Proc. SuperCollider Symp., Berlin. 2010.↩︎

Morimoto’s SuperCollider classes are available at: https://github.com/yotamorimoto/sc_c↩︎

See a screen recording from a December 2024 version of Knitting Factory at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UGaFKKoED1k↩︎

Gauge in knitting refers to the number of stitches and rows of knitting are required to achieve a standardized swatch of knitting, generally a 4” x 4” / 10cm x 10cm square. It is effectively the calibration system for knitters to reproduce published patterns accurately.↩︎

Wannamaker, Robert. “Mathematics and Design in the Music of Iannis Xenakis.” Xenakis Matters (2012): 127-41.↩︎

Testknitters are effectively beta testers who receive advanced access to the pattern and additional incentives in exchange for testing and giving feedback on the pattern during the testing period.↩︎

https://www.ravelry.com/designers/stephanie-pan↩︎

In fairisle knitting, the knitter knits with at least 2 different colored yarns at the same time, knitting with one color while ‘carrying’ the other color at the back of the work, switching colors as they knit. When large swaths of a single color are used, this requires the knitter to ‘catch’ the other color between stitches every few stitches to avoid very long ‘floats’ or lengths of unknitted yarn at the back of the work which can snag, break and impact the elasticity of the object being knit. This is often seen as an unpleasant necessity in fairisle knitting.↩︎

A continuous vertical column of a single purl stitch between knit stitches will effectively vanish due to the nature of the stitches. In order to preserve a vertical line in the knitted item, every other row must be knitted instead of purled in the vertical line to be effectively exposed↩︎

https://www.tue.nl/en/research/research-groups/making-with↩︎