Published September 2025 as part of the proceedings of the first Alpaca conference on Algorithmic Patterns in the Creative Arts, according to the Creative Commons Attribution license. Copyright remains with the authors.

doi:10.5281/zenodo.17084382

As an artist, quilter, and programmer, I’ve long been inspired by the North American tradition of patchwork quilting. While developing a media art project rooted in these traditional patterns, I was unable to find a comprehensive digital dataset of quilt patterns—so I built one myself. Since these block-based designs aren’t standardized or centrally archived, I created my own translation of the patterns I studied into encoded number formats. I identified and transcribed twenty-four base patterns, each represented as a nested table of numbered blocks in Lua. This dataset became the foundation for a series of creative projects that explore the intersection of traditional textile practices and generative digital art. By reframing quilting as a system of encoded design, this work transforms a tactile, cultural practice into a foundation for generative, code-based exploration.

In North America, a wide range of longstanding quilting traditions have evolved and been passed down through matriarchal quilting communities. These traditions differ in materials, techniques, and aesthetics, with older generations passing knowledge through collaborative gatherings such as quilting bees. Patterns and processes are preserved not only through practice, but through the physical and social act of making.1 In recent decades, techniques or patterns are also shared through books, websites, and video tutorials.

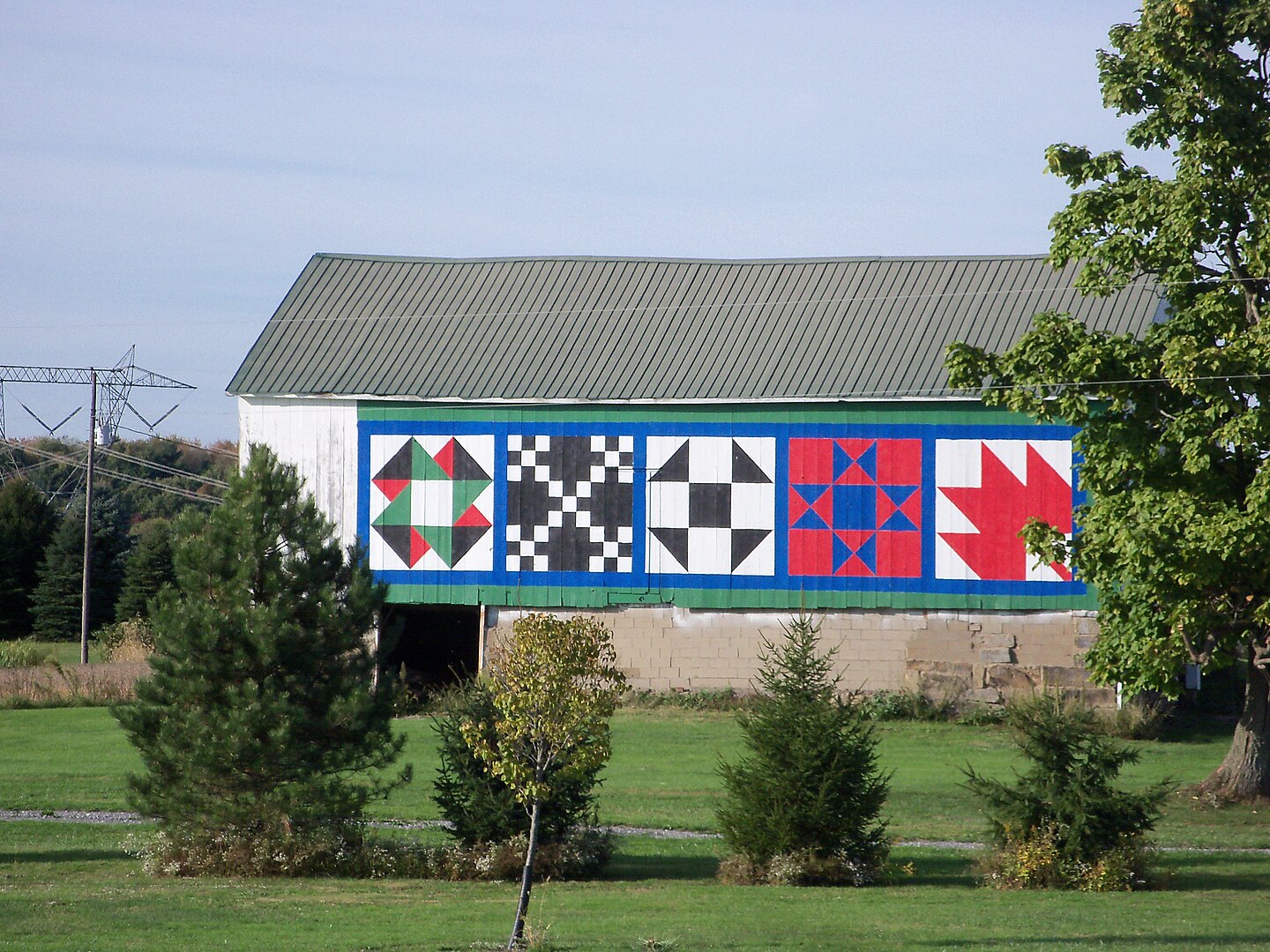

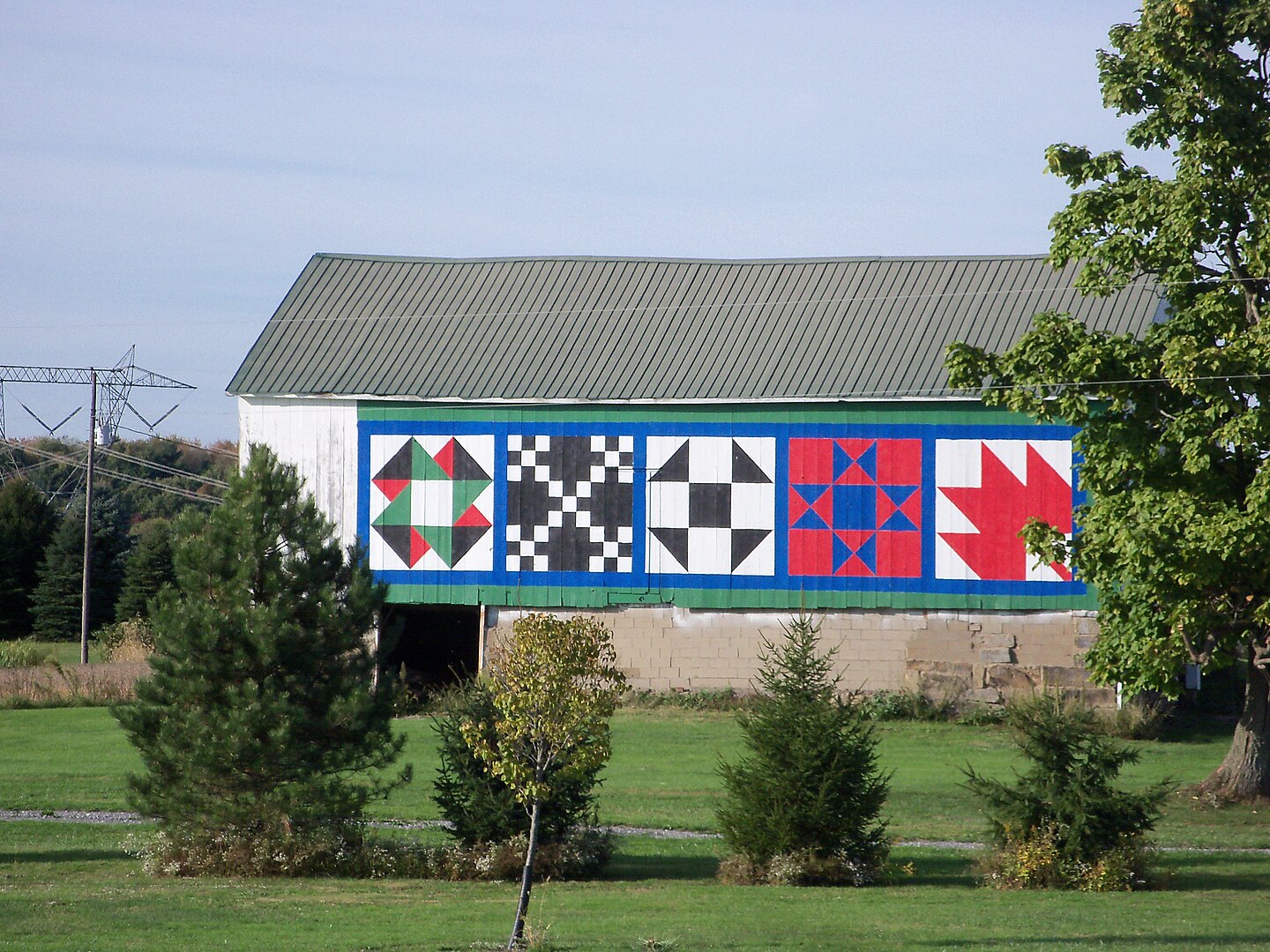

Long before I learned to program, I learned to sew. My mother, an artist who attended art school, taught me embroidery. Her embroidered work was influenced by the Amish quilts from our region of Pennsylvania.

I learned to sew clothing, and even started a small business making remixed clothes in college. I soon began quilting using discarded clothing and materials found in thrift stores or left behind on college campuses. Over time, newspapers, tyvek envelopes, and other found media started to make their way into these experimental quilts.

I’ve always admired the beauty of the Gee’s Bend quilts from Alabama—their work has been a guiding star for what a quilt can be.2 Like some of these quilters, I gravitated toward an improvised “lazy” assembling technique where fabric pieces are assembled intuitively, without measuring. In quilting, attaching fabric parts into blocks is called piecing, and one of the most basic pieced designs is the Log Cabin quilt: a pattern built from strips of fabric arranged in intersecting, often concentric blocks.

There are many variations on the Log Cabin, including the larger Housetop pattern, which typically consists of a single large block. In the Amish community near where I grew up, many quilts follow recognizably distinct formats—like Bars, Center Square, or Diamond-in-a-Square—each rich with geometric logic.3

As an artist, quilter and programmer, I’ve created a number of projects including games and interactive pieces that take quilting as both subject and structure.

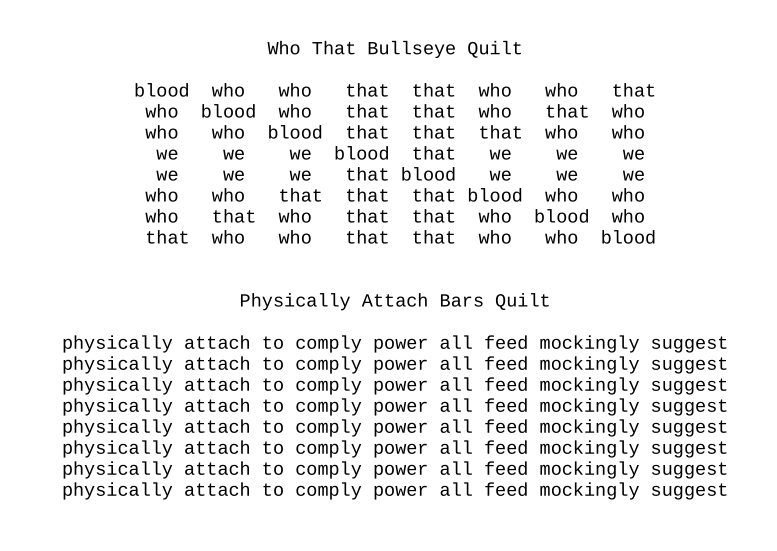

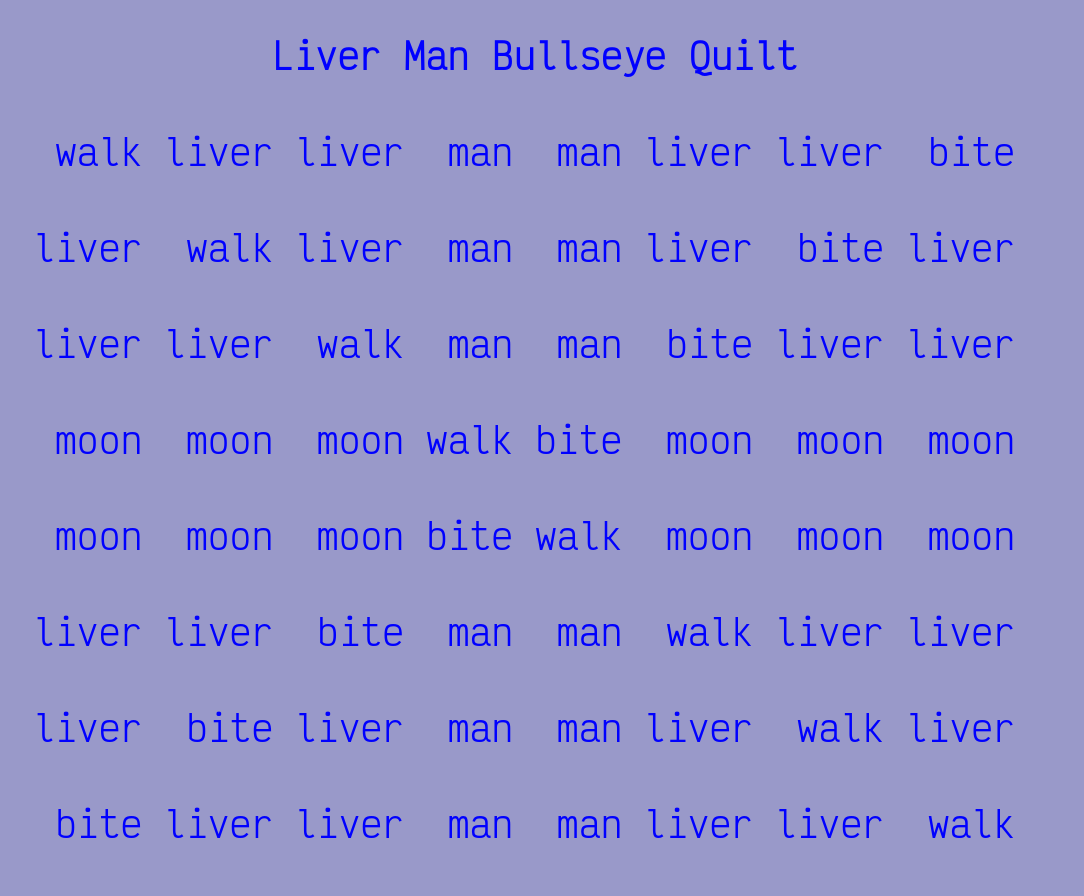

In November last year I participated in NaNoGenMo (National Novel Generating Month), a community event started by artist-programmer Darius Kazemi that invites participants to generate a 50,000-word “novel” through code.4 My approach was to generate visual poems in the form of quilts. I wanted to place words into a grid based on quilt structures, treating them as both design systems and poetic forms.

Because I couldn’t find a usable encoded dataset of quilt patterns, I decided to build my own. I developed a simplified system of 8×8 block-based patterns. These weren’t drawn from a rigorous academic taxonomy—they were personal selections, loosely defined by aesthetics and intuition:

The pattern categories I created include:

Some example encodings from the quilt table:

{ --housetop

{7,7,7,7,7,7,7,7},

{7,6,6,6,6,6,6,8},

{7,6,5,5,5,5,1,8},

{7,6,5,4,4,4,1,8},

{7,6,5,4,2,3,1,8},

{7,6,5,4,3,3,1,8},

{7,6,1,1,1,1,1,8},

{7,8,8,8,8,8,8,8}

},

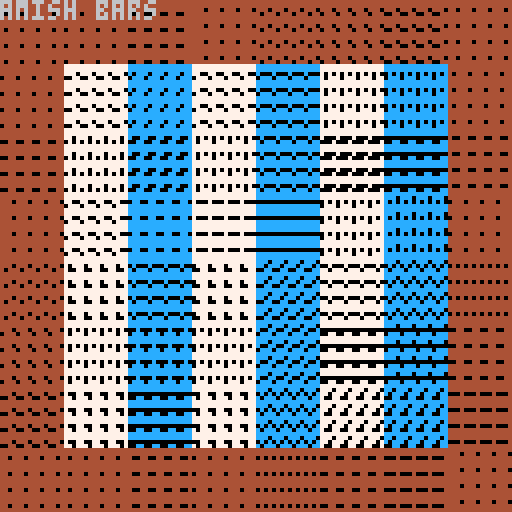

{ --bars

{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8},

{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8},

{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8},

{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8},

{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8},

{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8},

{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8},

{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8}

},

{ --bullseye

{4,1,1,2,2,1,1,5},

{1,4,1,2,2,1,5,1},

{1,1,4,2,2,5,1,1},

{3,3,3,4,5,3,3,3},

{3,3,3,5,4,3,3,3},

{1,1,5,2,2,4,1,1},

{1,5,1,2,2,1,4,1},

{5,1,1,2,2,1,1,4}

}In an early version of the poetry generator, I tested outputting color text and colored block backgrounds. This created the effect of color blocks with differently colored words. But I found I preferred the monochrome visual poems. For each generated poem a quilt pattern is randomly chosen. Then 8 source words are drawn from a selected category, which become the blocks of the piece. These are laid out programmatically according to the encoded design. Each poem is also given a title based on the selected words. In keeping with the spirit of NaNoGenMo I generated a “book” of poems, though I have also created smaller chapbook zines.5

This code was re-used, with minor variance where the randomness was seeded with the date, to create Daily Quilt Poem, a website that generates a new quilt poem each day.6 The library Fengari-web was used to interface the Lua code with Javascript in the browser.7 I chose a simple monospace font and colors for the title, background and text color in order to bring attention to the form of the poem and words rather than emulate blocks of color.

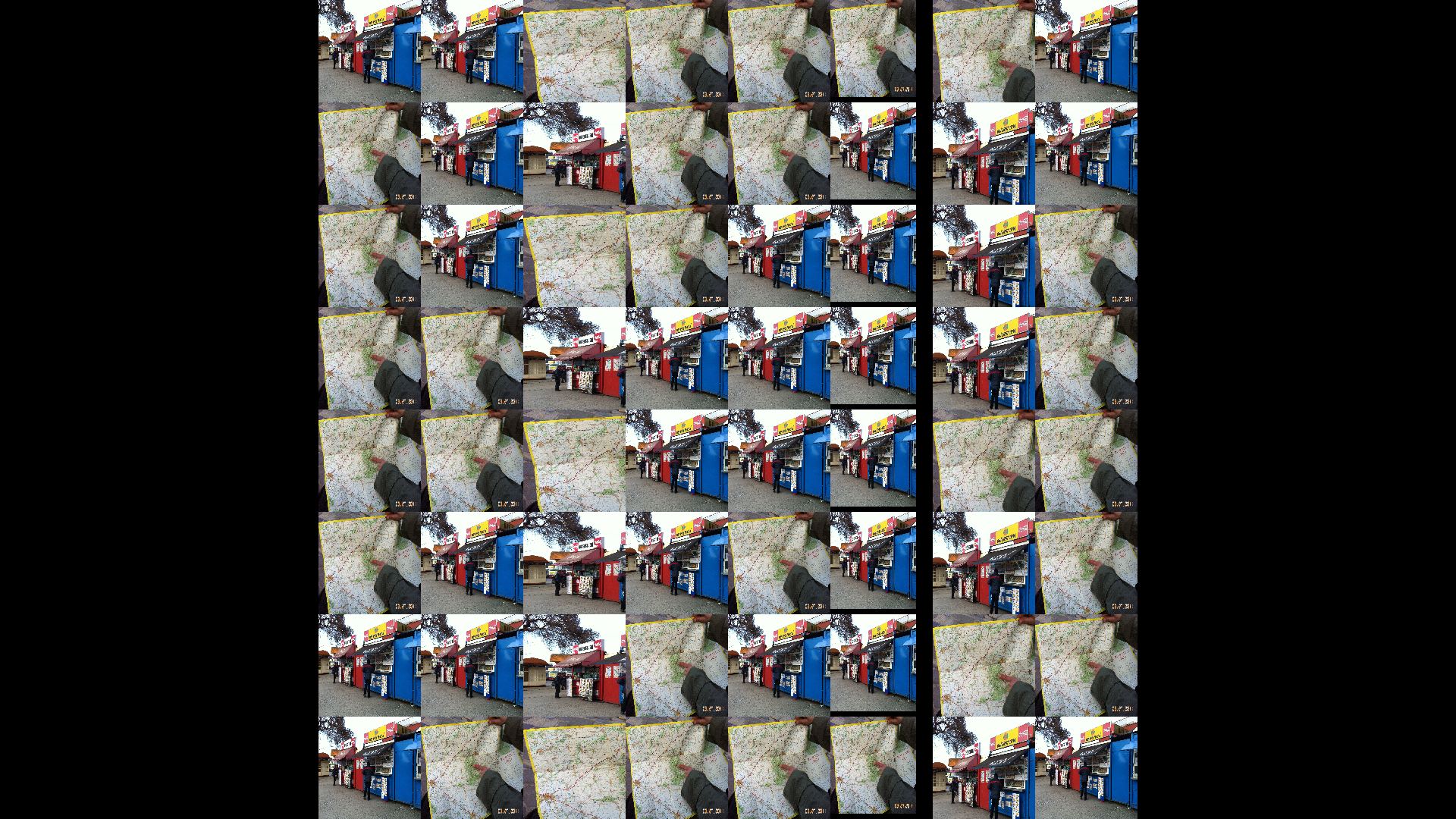

A few months later, I began another project—this time using my pattern dataset to generate photo-based “quilts”. I created two variations using the Lua-based framework Love2D, generally used in the creation of 2D games but flexible enough for creative coding projects.8

Both variations of my quilt photography project start with an archive of my own photography. Each photo quilt generated selects 8 photos to become the building blocks. In the first version, the output is static: 8 cropped square photo-blocks pieced into a pattern. In the second version, I animate the quilt—each block scans across a photo, creating a moving textile of image and structure. The result has a subtle, looping motion that evokes early video art, reminiscent in some ways of Nam June Paik.

In a third variation, I used the Pico-8 fantasy console—an intentionally constrained game engine with an integrated code editor and 16-color palette. This engine also uses a version of the Lua language. I imported my quilt dataset. The program selects eight colors at random, and then generates quilts using the encoded patterns. Each quilt fills the screen for one second before cycling to the next. While limited by resolution and memory, the Pico-8’s constraints encouraged a playful, reimagined approach to the form of a digital quilt.

All three projects use the same hand-encoded quilt pattern dataset, each exploring a different mode of recombination: text, photo, and color.9 While the tools and formats vary, each begins with the same idea—randomly selecting a vernacular quilt pattern, then assembling something new from its structure. Where traditional quilting appears to be a strict patterning system, there are generally many variations within the form. This is a natural result of human improvisation and experimentation. Rotating blocks, enlarging them, introducing spacing, and countless other techniques yield new approaches and patterns.

One challenge within my data encoding and the programs written was a question of how to account for this natural approach to pattern variants. In these initial works I chose a brute force technique where I added a number of variation patterns within the encoded dataset, but other approaches could be considered where new patches, colors, transpositions or rotations are programmatically added.

After my research and work began I was led to the practices of research scientist Mackenzie Leake and her patchwork quilt design tool PatchProv.10 This program allows quilters to digitally prototype and iterate on improvised patchwork quilt designs. Other programs by Leake include ScrapMap for selecting colors and assigning them to traditional quilt block patterns.11 These are inspiring design tools that point to additional generative and computational quilting tools to be developed further.

I see the work I’ve created so far as just the beginning. There’s more work to do: converting to other useful data formats, collecting additional patterns, expanding the dataset, encoding in larger formats and more detailed than the constrained 8×8 grid, and working with triangles and strips rather than solely blocks. I am also in process exploring methods using generative digital quilt pattern files in the creation of new textile works.

My hope is that others may build on these works—whether with my nascent quilt pattern dataset or by creating their own—and that these experiments can open up new ways to think with and through quilting. At its core, this work is about honoring craft while extending it into generative and digital spaces. It’s also a way for me to deepen my own understanding of quilting’s long history and help carry its patterns forward into new forms.

Staub-Wachsmuth, Brigitte. Patchwork & Quilting. Stackpole Books, 1989.↩︎

The Quilts of Gee’s Bend: A Slideshow. 1 Oct. 2015, https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2015/quilts-gees-bend-slideshow.↩︎

Bishop, Robert, and Elizabeth Safanda, editors. A Gallery of Amish Quilts: Design Diversity from a Plain People. Dutton, 1976.↩︎

NaNoGenMo. https://nanogenmo.github.io/. Accessed 9 June 2025.↩︎

Tusman, Lee. Lee2sman/Generative-Quilt-Poems. 2024. 1 Feb. 2025. GitHub, https://github.com/lee2sman/generative-quilt-poems.↩︎

Daily Quilt Poem. https://leetusman.com/everyday/293/. Accessed 9 June 2025.↩︎

Fengari-Lua/Fengari-Web. 2017. Fengari, 27 May 2025. GitHub, https://github.com/fengari-lua/fengari-web.↩︎

LÖVE - Free 2D Game Engine. https://www.love2d.org/. Accessed 9 June 2025.↩︎

Tusman, Lee. Lee2sman/Quilt-Pattern-Data. 2025. 10 June 2025. GitHub, https://github.com/lee2sman/quilt-pattern-data.↩︎

Leake, Mackenzie, et al. “PatchProv: Supporting Improvisational Design Practices for Modern Quilting.” Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems [Yokohama Japan], 2021, pp. 1–17. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445601.↩︎

Leake, Mackenzie, and Ross Daly. “ScrapMap: Interactive Color Layout for Scrap Quilting.” Proceedings of the 37th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology [Pittsburgh PA USA], 2024, pp. 1–17. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1145/3654777.3676404.↩︎