Published September 2025 as part of the proceedings of the first Alpaca conference on Algorithmic Patterns in the Creative Arts, according to the Creative Commons Attribution license. Copyright remains with the authors.

doi:10.5281/zenodo.17084386

“I have suggested to change the gramophone from a reproductive instrument to a productive one so that on a record without prior acoustic information, the acoustic information, the acoustic phenomenon itself originates by engraving the necessary Ritchriftreihen (etched grooves).” 1

In 1923, Bauhaus master László Moholy-Nagy proposed the above idea. At the time, it was just a provocation. However, nearly a century later, we have realized the idea with the help of mature computational technologies under a name of A record without prior acoustic information (2012-). 2 3 4 5

Instead of using the vibrations of original sound, we visualy draw a patterns of groove with a conventional vector graphics application (e.g., Inkscape, Adobe Illustrator).

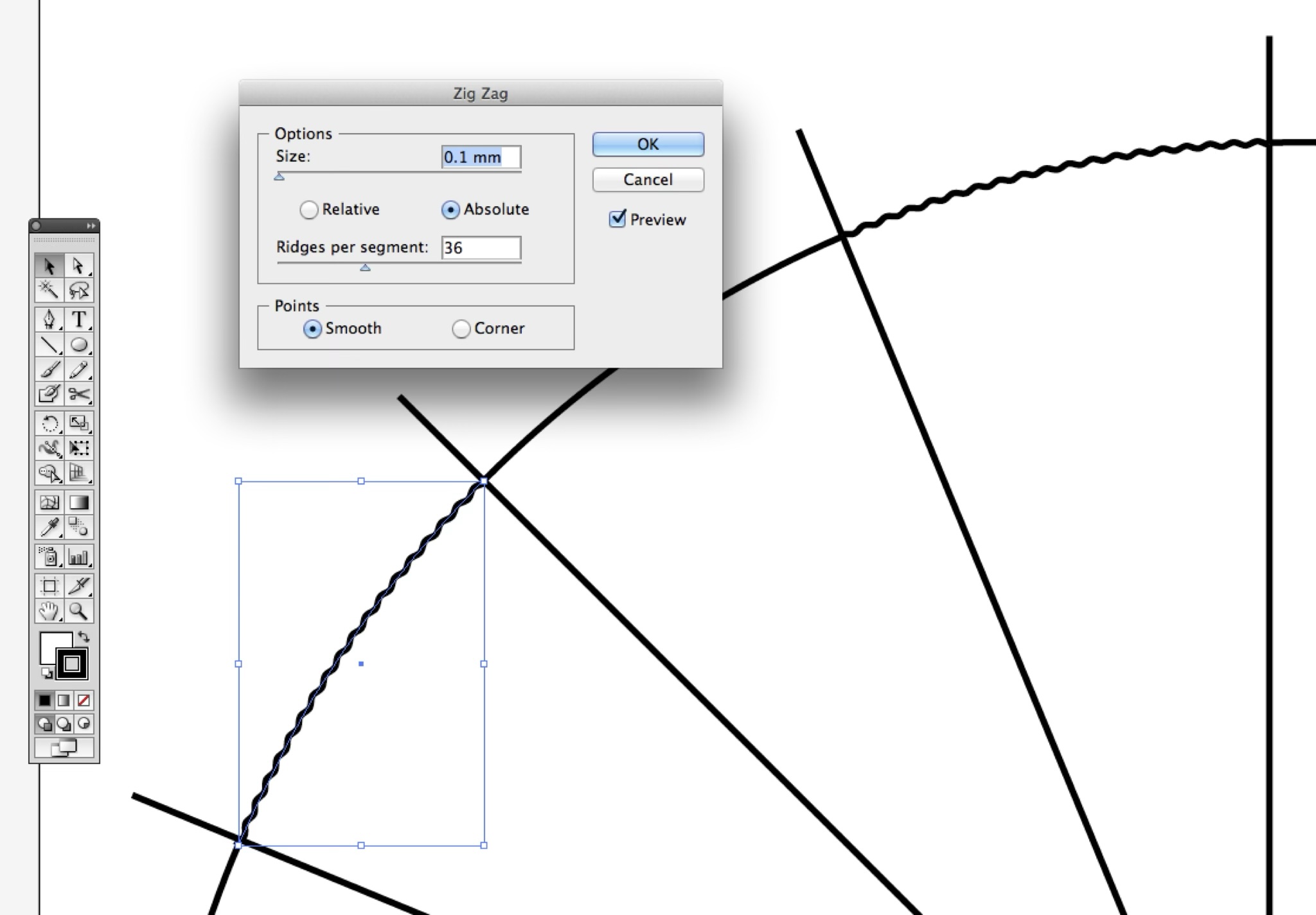

In Adobe Illustrator, the amplitude of the waveform is defined by the size of the zigzag, while its frequency is determined by the number of ridges per segment, according to the following algorithm:

\[ F = {Z \over 2} * { 360 \over A} *{RPM \over 60} \]

F = Frequency (Hz) Z = Number of Zig Zag A = Angle of Arc (0-360°) RPM = Revolutions Per Minute (33.3, 45, or 78)

In Inkscape, we developed an extension to enable this zigzag effect 6

Unlike standard cutting machines, we use laser cutters or plotters to engrave grooves. These grooves are cut horizontally into diverse materials—acrylic, wood, paper, metal, and porcelain—in a non-scalable, artisanal manner, instead of being produced in a scalable, mass-production process on vinyl using a stamper. The results can be played on ordinary turntables.

In early 1960’s, a Czech artist Milan Knizak started to create music from defective, worn, damaged or broken LP’s. He began sticking tape on top of records, painting over them, burning them, cutting them up and gluing different parts of records back together, etc. to achieve the widest possible variety of sounds’ in a name of Broken Music 7.

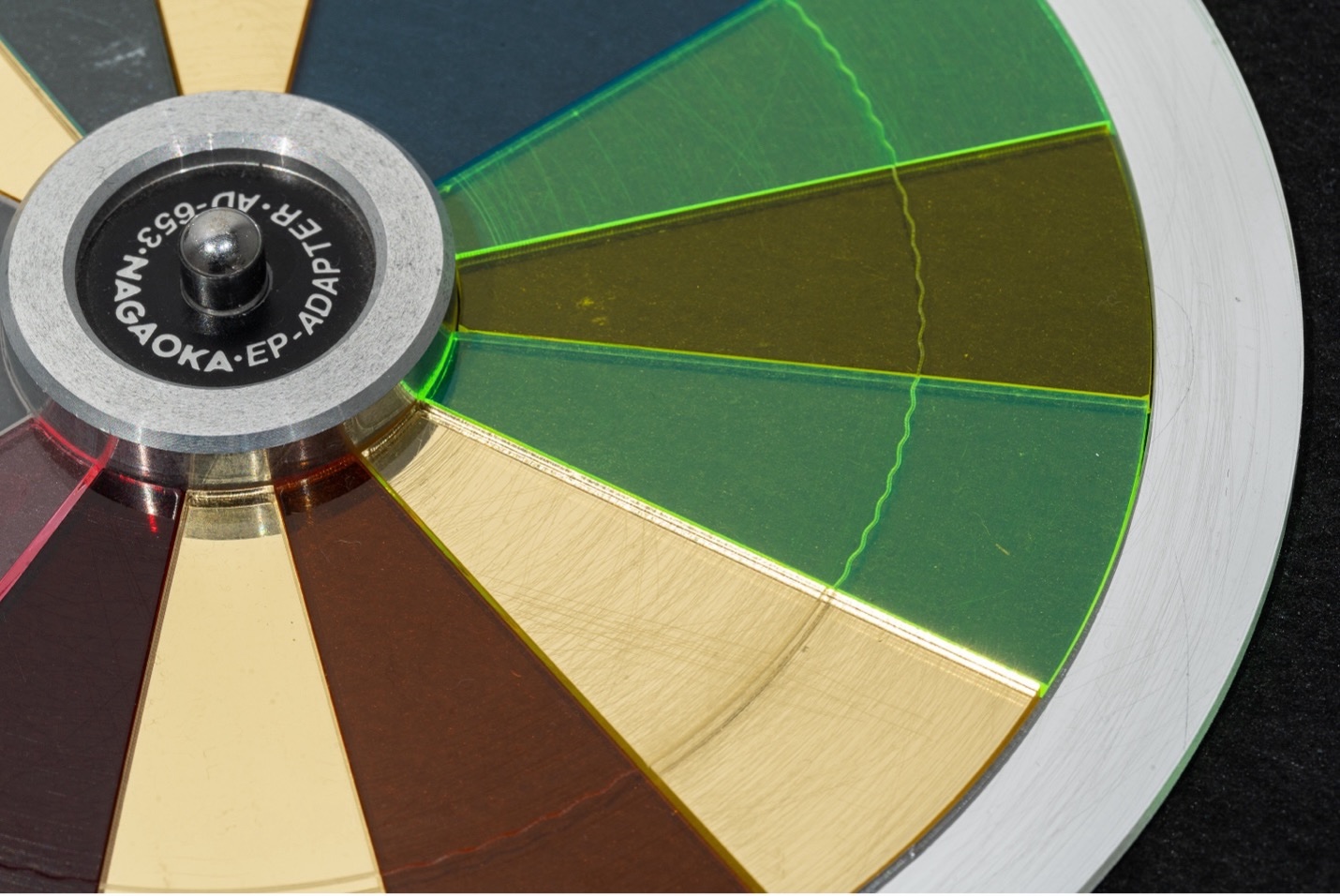

Fragmented Music (2014) is a work of A record without prior acoustic information which got influenced from Broken Music in part. Instead of directly damage existing vinyl records, we engrave different patterns of groove in the form of arcs of various angles onto differently colored acrylic plates with a laser cutter.

Each color corresponds to a specific number of zigzags (i.e., frequencies, ranging approximately from 60 to 120 Hz at 33 RPM). Gold segments represent silence with its smooth curved lines, and a silver outer ring prevents centrifugal scattering. The groove endpoints of each arc are centered for connectivity. To prevent needle skipping between arcs, the laser focus is blurred to increase groove width.

Using two sets of the work, one can physically rearrange the series of arcs into looping sequences to spin one after another with a standard analog DJ setup (i.e., turntables and a mixer).

Sound 1: Fragmented Music performed by L?K?O at Dommune (2022) (Note: Later parts of the performance include additional music and effects.).

As described at the beginning, the foundation of the work is an algorithm that produces arbitrary frequencies through a zigzag pattern resembling a sine wave, determined by the angle of the arcs and the RPM of the turntable.

In this system, each colored segment represents either a frequency or silence, and the entire series of arcs functions as a loop. As the turntable continues to spin, manipulating the order of the colored segments generates different sequences, akin to rhythmic patterns.

Even without drawing actual groove patterns, skipping the needle to the edge of the arcs causes rich variations of sonic emptiness that resonate with works such as Maria Chavez’s Plays (Stefan Goldmann’s ‘Ghost Hemiola’). Deviations from a sequence of grooves unfold into shifting rhythmic textures arising from the gaps between arcs at different angles.

In the discussion “The Future of Music and Recorded Music” 8, Japanese composer Masahiro Miwa described our project as follows:

“In my view, it’s like hacking recording media to demonstrate sound synthesis. Typically, sound synthesis is done with electronic circuits or similar means, but in this case, it results in being engraved on the medium of records. So, it’s intervening directly with the recording media and demonstrates the process.”

In this context, our work—including Fragmented Music—can be considered as a kind of sound synthesis device akin to analog synthesizer.

On the other hand, Japanese sound studies scholar Katsushi Nakagawa observed our work as:

“I would like to draw attention to the fact that these records produce sounds that seem to be nothing but electronic tones. […] When played back on a record player, these records engraved with mechanical and physical irregularities but devoid of any electronic processing of the sound, start emitting thick, rhythmic electronic-like bass tones. It’s a curious sight or auditory experience. We can’t help but feel a strange sensation as if we have been tricked.” 9

Here Nakagawa highlights that audiences are not listening to an “original sound” but rather perceiving an acoustic production system. What they perceive is not a faithful reproduction of an original sound but an acoustic artifact shaped by mechanical inscription.

Given this, and Fragmented Music’s ability to generate alternative rhythmic relationships by reconfiguring patterns, the work may be better described as a hybrid musical instrument—combining a non-electric synthesizer and a step sequencer—disguised as a record on a turntable.

A French Philosopher Jacques Attali noted as

“In music, the instrument often predates the expression it authorizes, which explains why a new invention has the nature of noise” 10

If accurate, the series of grooves in Fragmented Music may represent an alternative history of music—one in which recording and playback technologies are repurposed to create, rather than reproduce, sound by engraving groove patterns, originally drawn as images in software, onto the surfaces of acrylic fragments.

This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (Grants JP23H00591 and JP23K17267)

Moholy-Nagy, László. New Plasticism in Music: Possibilities of the Gramophone. In Broken Music. Artists. Recordworks, edited by Ursula Block and Michael Glasmeier, Berlin: Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD and gelbe MUSIK, 1989.↩︎

Jo, Kazuhiro and Ando, Mitsuhito. Cutting record-a record without (or with) prior acoustic information. In Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression. 2013, pp. 283-286, 2013.↩︎

Jo, Kazuhiro. The role of mechanical reproduction in (what was formerly known as) the record in the age of personal fabrication. Leonardo Music Journal 24,pp. 65-67, 2014.↩︎

Jo, Kazuhiro. Making a Paper Record - a record without prior acoustic information. International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression 2022 workshop, 2022. https://nime.pubpub.org/pub/7z30mwzm↩︎

Jo, Kazuhiro. Examining the Notion of Recording: “A record without prior acoustic information” (2012–), “Mary Had a Little Lamb” (2019), “We Were Away a Year Ago” (2023), and “Fermenting Sound (tentative)” (2024–). In Proceedings of Speculative Sound Synthesis Symposium 2024, 2024. https://speculative.iem.at/symposium/docs/proceedings/jo/↩︎

Miyashita, Keita(koma-koma). inkscape-zigzag. https://github.com/koma-koma/inkscape-zigzag↩︎

Block, René, et al. Broken music: artists’ recordworks. Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD, 1989.↩︎

Jo, Kazuhiro, Miwa, Masahiro, and Matsui, Shigeru. The Future of Music and Musicology. Journal of the Institute of Advanced Media Arts and Sciences 5: pp. 98-101, 2014.(In Japanese)↩︎

Nakagawa, Katsushi. What Is Sound Art. Nakanishiya Shuppan, p.178, 2024. (In Japanese)↩︎

Attali, Jacques. Noise: The political economy of music. Manchester University Press, 1985.↩︎