Published September 2025 as part of the proceedings of the first Alpaca conference on Algorithmic Patterns in the Creative Arts, according to the Creative Commons Attribution license. Copyright remains with the authors.

doi:10.5281/zenodo.17084396

(authors are ordered alphabetically)

Our new collaborator arrived in a long rectangular box, stretching the table. Under the guidance of our instructor, we carefully assembled the machine, attaching the two long antennae—features that gave it an animal-like appearance—as they protruded behind the frame, swaying and facing us. These would guide two yarns of different colors, holding them in place to be driven across an array of hooks by a carriage that looks like a cassette player fused to an electric iron. With each turn, the carriage is driven across by hand; the hooks protrude or retract, determining the pattern of the interwoven yarns, row by row, while triggering a satisfying series of precise clicks. The casing, of a gentle, institutional beige color typical of the 70s, was opened in part, with a microcontroller dangling from it. This old machine had been given a new brain! This allowed us to bypass the need for inserting black-and-white pattern cards, and instead send digital instructions directly from a computer, to be transformed into a knitted textile mesh.” (Course participant)

In the fall of 2024, a group of PhD students from the University of Zürich (UZH) and MA students of the Zürich University of the Arts (ZHdK) joined a course somewhat grandiosely titled Weaving Sustainable Digital Future Stories. Course participants were invited to navigate the intersections between textile crafts; the cultural act and digital patterns of writing; urgent questions of sustainability; and the transformative possibilities of digitalization.

“Weaving sustainable digital future stories” originated from a dialogue between sustainability.discourses,1 a computational social science project at UZH, and the ZHdK MA Transdisciplinary Studies in the Arts.2 sustainability.discourses was a project aimed at extracting and understanding discourse on urban sustainability in Zürich from large volumes of media data. Ludwig Lederer, one of the eventual course designers, was invited to visit the project for half a year as a transdisciplinary artist in residency.

The resulting conversations on the practice of distant reading inherent to many computational approaches in working with text, where digital streams of text are processed in a way distinct from the context they were both written in and meant to be consumed, started coalescing around a set of concepts and key metaphors. Did the project look for patterns “woven” in the “fabric” of discourse around sustainability? How did the digital nature of the data studied to understand sustainability discourses shape the way digitalization itself was treated in its relation to sustainability?

We decided that the best way to approach these questions would be in a lab setting, with students with both arts and research backgrounds. Ludwig Lederer, Mario Angst, Nicole Frei and Irene Vögeli developed a lab program to translate techniques of discourse mapping towards tangible objects processed on textiles. Sustainability, storytelling and digitalization would mark three broad conceptual markers defining the course. To tie them together, we returned to one of the most prevalent metaphors we had gravitated toward in discussions - weaving or textile crafts more generally, which would ground the lab materially.

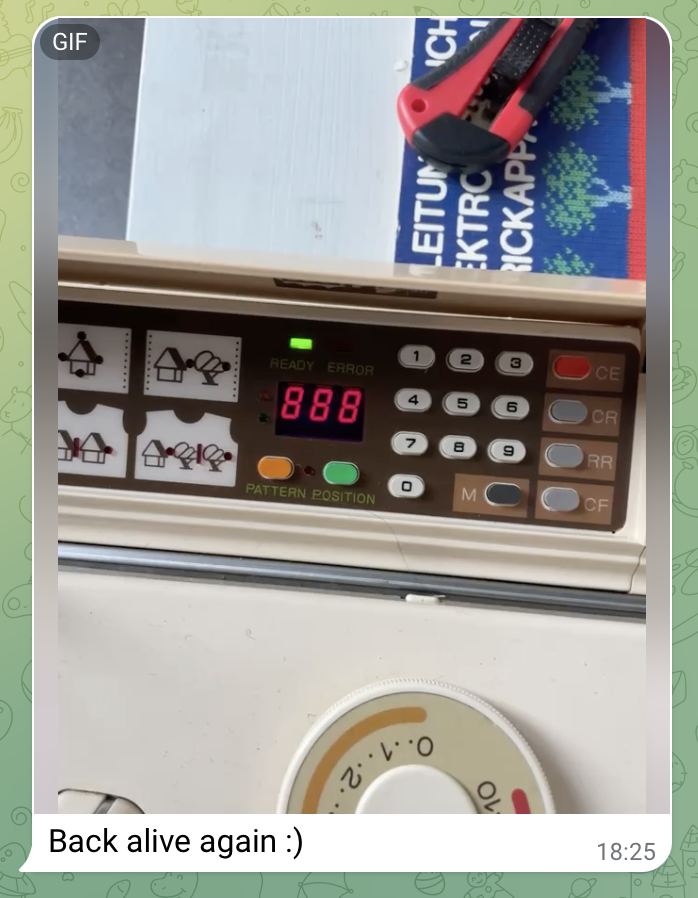

What we did not realize when planning the course itself, was that we would acquire a participant in the course, whose pattern-making capacities would in many ways come to profoundly influence the projects of course participants. That participant was a Brother KH-910 knitting machine, likely produced at the end of the 1970s. By sharing our knowledge from our different background disciplines, of whom one is a Fashion Designer, we saw the potential of connecting our topics and make it tangible in a practical way by working with an electronic knitting machine. The Brother KH910 marks a transition from analogue to electronic knitting machines. Unlike the older punch card models, it does not rely on mechanical punch card control but instead uses an electronic control panel with an integrated pattern memory. Patterns can be digitally entered, stored, and modified via the LED display, while the machine electronically selects the needles. The actual knitting process, however, remains hand-operated, as the carriage must still be moved manually. In this sense, the KH910 is an early hybrid solution, combining digital pattern control with traditional hand operation, paving the way for later computer-compatible models.

The machine made its way to us from Germany, where we found it on a classifieds ad. While exploring the space drawn up by textile crafts, sustainability and digitalization we had come across the AYAB (all yarns are beautiful)3 project, which provides software and instructions to control machines from the Brother KH-9xx range of knitting machines from a computer (through an Arduino microcontroller and custom shield). In many ways, it fit the space our course aimed to move in perfectly - the AYAB project’s way of revitalizing past machinery through open-sourced collaboration illustrated an often unkept sustainability promise of digitalization.

After some trial and error and even a small smoke cloud from a short circuit, we gradually restored the machine and became familiar with its workings. With the support of tutorial videos4 and manuals56, we set it up for the lab, introduced course participants to its use, and developed open-source software to make it easier to create two-color images that could be transferred to the machine for knitting.78

In subtle and not so subtle ways, the presence, possibilities and limitations of the hacked knitting machine shaped outcomes and work conducted within the course. In the following, we present a selection of three works by participants of the Weaving Sustainable Digital Future Stories lab. All works explored the possibilities of textile pattern-making at the intersection of digitalization and sustainability.

Inspired by the seminar’s theme of “weaving sustainable future stories”, we became interested in how ecological systems intertwine beyond human grasp.

“In nature nothing exists alone.”9

This quote from Rachel Carson became an undercurrent throughout our process. Everything in our world is interconnected, interwoven, a layered mesh that unfolds across scales of time and space beyond comprehension to the sentient mind. The attempt to grasp these hyperconnected realities requires a deliberate alteration of perception.

How could we communicate our not-yet fully explored concept via the

medium of knitted yarn and pattern, especially when limited to two

colors? We decided to augment this limited binary spectrum by knitting

with properties of conductivity and non-conductivity as well. One thread

was a neutral yarn, and the other was a special conductive thread. When

the knitted fabric is touched or squeezed, the interaction

short-circuits some of the conductive rows, reducing the overall

resistance of the textile. The textile would function as a resistor,

which we then incorporated into a voltage divider circuit. Touching and

interacting with the fabric meant changing the resistance, and hence the

voltage output of our contraption. We attached an ESP-32

module to read this output and to modulate the speed of an audio

sequence played from the ESP DAC pin. Initially, the audio

was played at a frequency too low to be understood as speech. To reveal

its meaning, the piece needs a human interlocutor: through interaction,

the manipulation of the fabric, the frequency shifts, rising into a

perceptible range and the spoken words become intelligible.

Figure 4: Left – Schematic drawing of the voltage divider circuit incorporating the conductive fabric. Right – Interaction with the woven cloth.

The work seeks to demonstrate the necessity of altering representations of time and space to perceive hyperobjects, interconnected events and realities that otherwise escape our limited senses. It challenges the viewer to confront the limitations of human perception when exposed to information streams beyond perceptible scopes and ranges.

Conceptually, the piece reflects on the presence of everything that normally escapes our perception: things too fast, too slow, too small, or too big to understand, also referred to as hyperobjects in ecological thinking.

“We have only to speed up our sense of time to see how strange life forms are. They arise, flicker, and vanish.”10

Sybille Krämer speaks of the performative materiality of media: the way material forms are not just carriers of information, but shape the very conditions of knowledge and meaning.11 This moment of coming-into-understanding is not merely a technical feedback loop, but also a performative and medial experience in which touch becomes a method for inquiry, exploring a form of storytelling that is not linear or didactic.

Media do not only symbolize; they make sensible by enabling aisthesis, the tension between event and perception. In our piece, information becomes accessible only through embodied interaction, a deliberate shift in perspective. The act of touching the material changes not just electrical voltage, but the very conditions of perception: the fabric becomes sensor, interface, and carrier of meaning, but only within the mode of a situated, bodily experience.

In Mapuche culture—a First Nation originating from the territory now called Chile—there are numerous symbols used to convey a wide range of messages: from social status and communal territorial identity to gender distinctions. These symbols are primarily expressed through textiles, an ancestral practice deeply rooted in Mapuche identity and, along with silverwork, one of the few cultural forms that have historically been acknowledged as “art” by the dominant society.12 Textiles have long served as surfaces where knowledge, memory, and rakiduam (Mapuche wisdom) are inscribed, creating a living language. Despite the disruptions caused by colonial violence and extractivist models that limited the transmission of this knowledge, weaving has persisted and is today undergoing processes of revitalization that speak to its role as a form of resistance. In this sense, weaving is not only a material technique but also a system of signs. The Mapudungun term wirin—which can be understood as line, trace, design, or even writing—reflects how woven motifs carry stories and meanings.13 Many weavers recount that the creation of designs and symbols can also emerge through pewma (dreams), a spiritual way of learning and receiving knowledge fundamental to Mapuche textile practice.14

In the 1980s, one of the consequences of the neoliberal model imposed by Chile’s military dictatorship was the massive privatization of Indigenous lands. Many of these lands were acquired by foreign forestry conglomerates, mostly from the Global North. From that point on, intensive land exploitation replaced native forests with monocultures of exotic species such as eucalyptus and Radiata pine (Pinus radiata), selected for their fast growth, adaptability, and commercial yield. This transformation not only caused deep and often irreversible ecological damage, but also dispossessed communities of fertile territories, displacing them to marginal lands. The way these trees are planted—in dense, straight, homogeneous rows—stands in stark contrast to the unpredictable, diverse growth of native forests. What was once a living and complex ecosystem has been replaced by an artificial, rigid, and repetitive landscape.

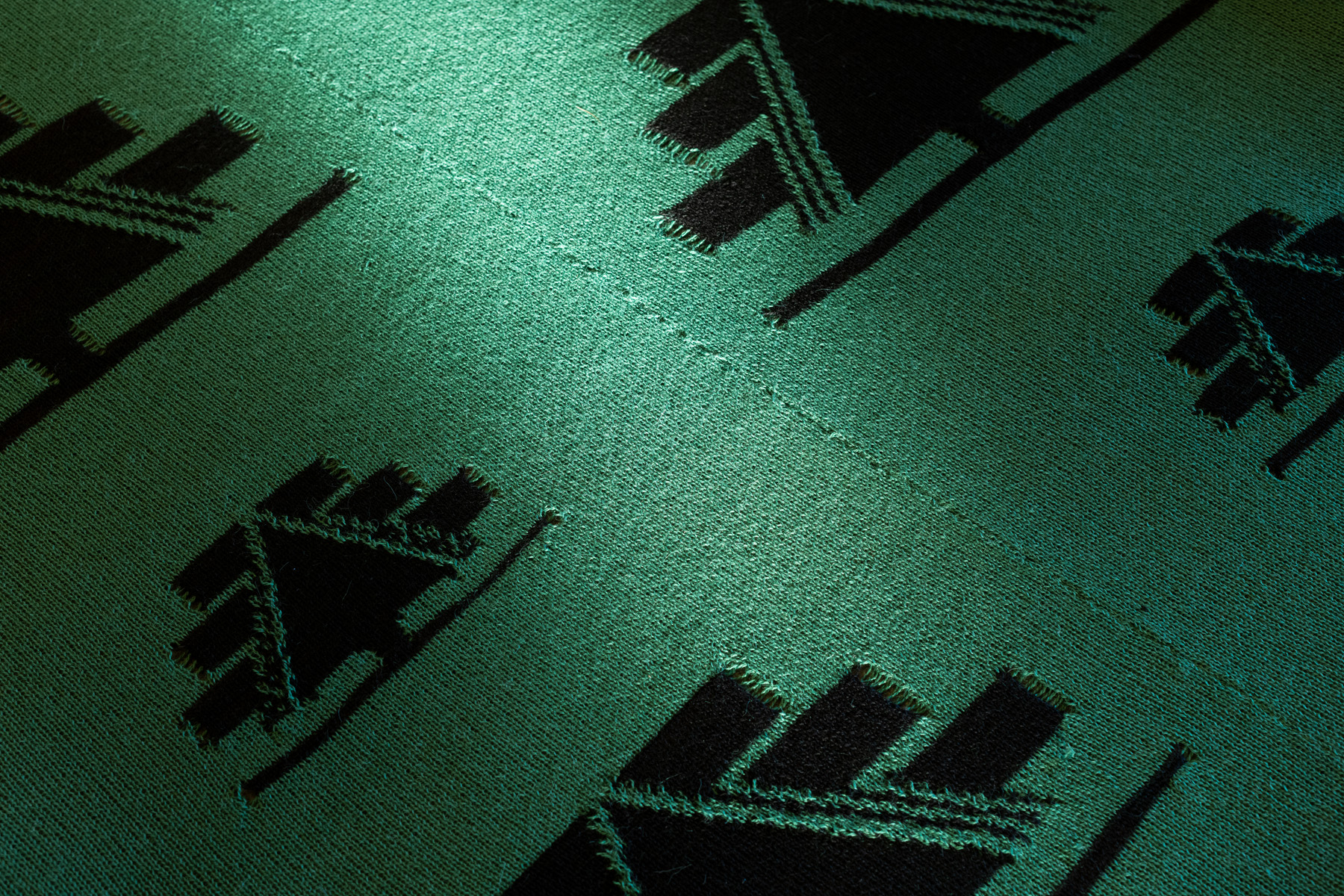

This project translates the traditional Mapuche witral weaving technique into a hacked, electric knitting machine, aiming to visually reproduce that artificial landscape: repetitive, green, linear. The pattern used is the symbol of the tree (Aliwen in Mapudungun), which, according to my research, does not refer to a specific species but rather to the general idea of a “tree.” To create the design, I used images from the Portal de Contenidos Epewtun,15 a Chilean website providing a bank of images from different Indigenous nations of the Chilean territory in editable Illustrator and .jpg formats.

After downloading the image of the tree, I adapted the format by repeating the symbol four times, alternating two sizes—one larger, one smaller—using Photoshop. To reach the desired width for the textile, I arranged the design in two columns, inverting the sizes from the first piece. Several tests were required to adapt the file for the program to reproduce it correctly, until arriving at the final version, thanks to the guidance and patience of Nicole Frei, one of the mentors at the Lab Weaving Sustainable Digital Future Stories. Once both pieces were ready, I hand-stitched them together in the center and added a thick grey fabric to the back to keep the textile extended.

The Mapuche textile technique is not only about design but also a profound understanding of the surrounding environment. Weavers collect plants for dyeing, shear animals for wool, wash, spin, dye, and dry the fibers, and then prepare them for the witral loom. In addition to weaving, symbols can be expressed through dyeing and knot systems, creating forms that hold meaning for the wearer and the community. The body that weaves changes as well: working with the witral involves time, precision, and a physical-spiritual connection to the act of weaving. In contrast, working with the machine is faster and more efficient. This experience confronted me with the differences between both modes of making, leading me to reflect on the role of textile art as a critical tool. Thus, this work is not just a woven piece: it is a visual and embodied statement on the tension between tradition and industrial production, between nature and monoculture, between territory and displacement. In this context, weaving also becomes a political act.

These days, I’m surrounded by labels on products claiming to be eco-friendly. While I think it’s a good idea to have such labels, I often wonder: who is actually issuing them? Often, it’s the companies themselves. In that case, the label becomes just another part of the advertising. It subtly steers you toward the “right” choice of what to buy. I find that strange. The meaning behind these labels feels hollow—symbols that appear soothing but say very little, stamped onto food and consumer goods. The green deal. Buy yourself a piece of the fight against climate change.

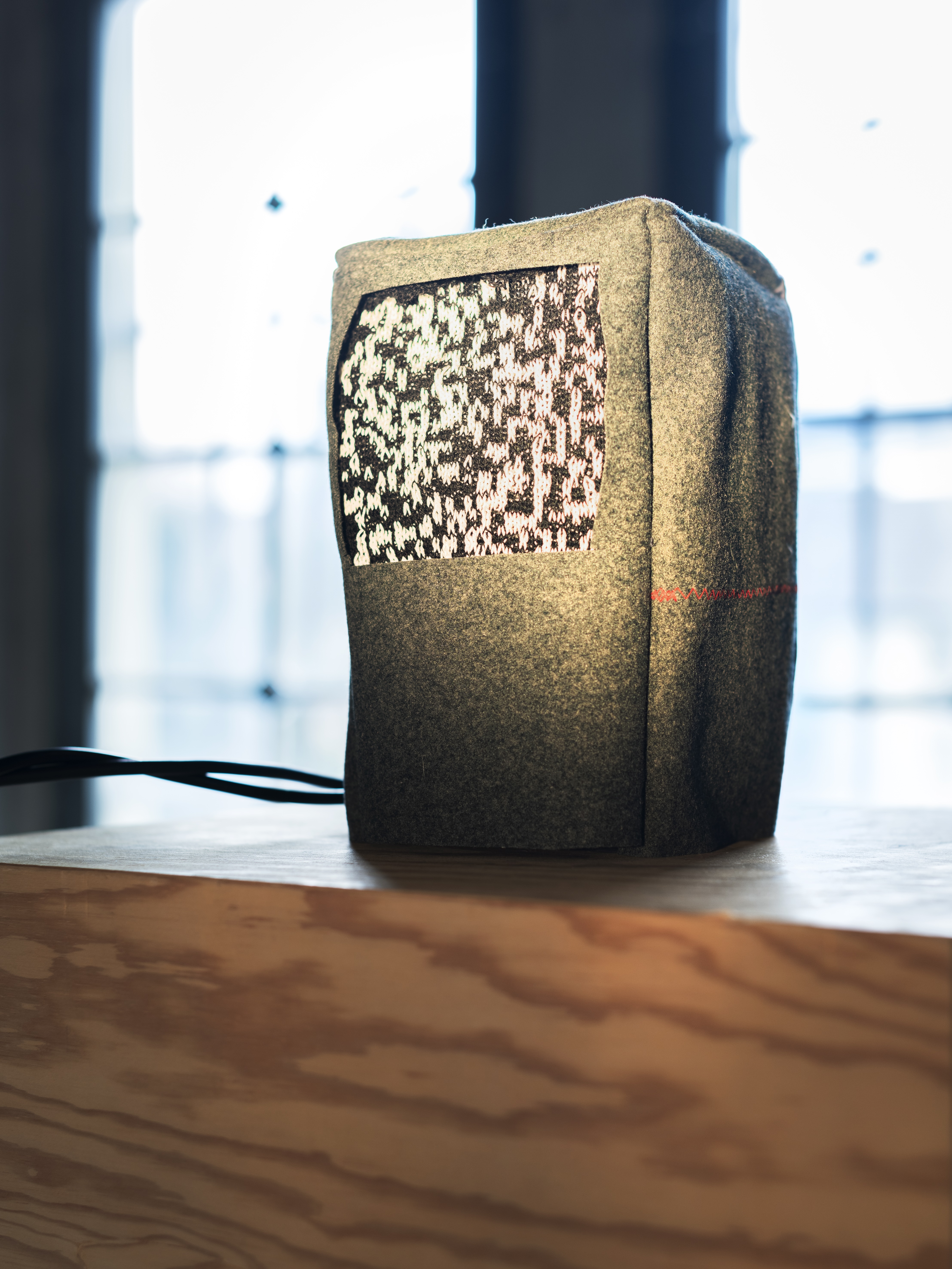

These symbols rarely prompt deeper questions like: Where did this product come from? Is it truly sustainable? Instead, they do the thinking for you. They offer a kind of moral pass—a way to consume without guilt. Over time, they became meaningless to me. So, instead of crafting these green labels full of supposed meaning, I decided to create something deliberately devoid of information. I came up with the idea of knitting screen noise—random dot patterns like those seen on an analog screen when there’s no signal. So it became a journey of translating information into non information via the knitting machine and make it available on other levels of perception than just the eye sight. I loved the pattern making with the knitting machine and dealing with its quirks together in our group. It was somehow a nice collaborative experience. The knitting itself felt rather strange and less social. It was harder to have a conversation while knitting because of the thread pushing and pulling which you have to do manually and requires quite some force. Then I combined my patterns with old felt-pieces and created “screen savers” to place over loudspeakers. The speakers played a sound composition made of white noise and blips—sounds I had previously used in an acoustic guidance system while working on stage with a blind person. So in a way there where two levels of transformation happening in my work White Noise. One was the Transformation from pictograms depicting ecofriendly production (Information) to noise (Non-Information). Also there was the transformation from an accoustic guidance system to a non guidance system.

I hope White Noise creates a space where there’s time to reflect. A place to mourn, just a little, the overwhelming scale of the climate crisis. And perhaps, to reach a quieter state of acceptance—which can be the ground for taking further steps. We have plenty of information and our knowledge is getting bigger and bigger every day in every direction. Highly specialised skills applied in highly specialised fields. Sadly on the big scale it does not seem to help us to do the right thing as a society as a whole to save nature and resources for further generations. Maybe what we did in our course together, helped building little bridges between disciplines, where underneath there is an oppening space, ready to be filled with collaboration between all kinds of fields and disciplines.

Across the course of Weaving Sustainable Digital Future Stories, the metaphor of weaving proved to be more than a thematic anchor. It became a structuring principle that shaped our thinking on multiple levels: materially, conceptually, and methodologically. The hacked Brother KH-910 knitting machine was not just a tool, but an active participant whose material presence, constraints, and capabilities influenced what could be imagined and realized. It acted as a catalyst, a conceptual interface, and a companion that opened space for reflection, critique, and alternative ways of knowing. As a hybrid between the analogue and the digital, the KH-910 exemplifies how historical technologies can be reactivated to bridge handcraft and technical processes, renewing their relevance for contemporary inquiry.

In each project, the act of textile making became a way of telling stories and navigating complexity. Whether engaging with ecological interdependencies, Indigenous systems of knowledge, or the sensory limits of perception, the technique of knitting emerged as a practice of assembling meaning.

The transdisciplinary setting of the lab, drawing from the arts and computational social science research, enabled a form of inquiry that was both situated and experimental. Making became a method of thinking and a way of staging new relationships between humans, machines, and materials. Revived through the open-source AYAB project, the KH-910 machine connected analogue pasts with digital futures. It reminded us that digitalization is not only about efficiency or abstraction, but also about reactivation, repair, and embodied experience.

Each contribution used the machine to explore tensions between visibility and obscurity, and between control and unpredictability. The three projects examined textile crafts as a method of sensing and thinking differently. In Nature Nothing Exists Alone translated ecological entanglements into a tactile interface where meaning could emerge only through embodied interaction. This Is Not a Forest recontextualized traditional Mapuche weaving symbols within a mechanized process, reflecting on the impact of monocultures and the displacement of Indigenous knowledge systems. White Noise used knitted surfaces devoid of symbolic content to create space for mourning and quiet reflection in response to the commodification of sustainability.

The project points toward the potential for building community that extends traditional knitting circles by intertwining embodied craft knowledge with digital practices, positioning it within a contemporary context in which nearly every facet of society is shaped by digital technologies. One key benefit offered by interacting with historical machinery to tell stories about the future in a community context is a reframing of hegemonic narratives around digitalization. Repurposing old machinery through digital means can put into question deeply ingrained stories about both digitalization’s relation to obsolescence and its inevitability, which is otherwise hard to achieve.

The lab’s approach could be adapted and scaled within community contexts and educational environments. The heterogeneity of user groups, ranging from artists and designers to programmers and makers, underlines the machine’s capacity to operate as a bridge between different domains of knowledge. For example, programmers unfamiliar with textiles and textile practitioners unacquainted with coding expanded their knowledge by learning from one another.

To work beyond the machine is to trace connections not only across yarns, but also across cultures, temporalities, and epistemologies. The KH-910 helped to initiate these explorations through its capacity to engage with materials, through its ability to provoke thought and to open new perspectives. Together, the projects formed a collective exploration of sustainable digital futures. These are futures shaped not by speed or simplicity but by layers of reflection, resistance, and relation. In this process, the lab did not offer solutions but created openings. Each work became a thread in a larger fabric of inquiry.

Mario Angst, Neitah Noemi Müller, and Viviane Walker. “Automated Extraction of Discourse Networks from Large Volumes of Media Data.” Network Science 13 (2025): e4. https://doi.org/10.1017/nws.2025.4.↩︎

Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK). “Transdisciplinary Studies.” 2025. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://www.zhdk.ch/en/degree-programmes/transdisciplinarystudies.↩︎

AYAB Project. “AYAB – All Yarns Are Beautiful.” 2017. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://www.ayab-knitting.com.↩︎

KnitFactoryImpl. Intro to Brother 910 Standard Gauge Knitting Machine feat. Rachel. YouTube video, 2025. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-2-l4-icr_c. ↩︎

AllYarnsAreBeautiful. AYAB Manual, Version 1.0. 2024. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://manual.ayab-knitting.com/1.0/.↩︎

Machine-Knitting.net. “How to Fix a Brother KH930 Knitting Machine with ‘Won’t Turn On’ or ‘No Power’ Fault.” n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://www.machine-knitting.net/machineknittingnet/how-to-fix-a-brother-kh930-knitting-machine-with-wont-turn-on-or-no-power-fault/.↩︎

ayab.discourses.ch, “Web application to make images suitable for two-color knitting on Brother KH-910 machines”, n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://ayab.discourses.ch.↩︎

Mario Angst. “rayab-web.” GitHub repository. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://github.com/marioangst/rayab-web.↩︎

Rachel Carson. Silent Spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1962.↩︎

Timothy Morton. Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.↩︎

Sybille Krämer. Medium, Messenger, Transmission: An Approach to Media Philosophy. Translated by Anthony Enns. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015.↩︎

Carmen Valentina Paillahueque. Notas preliminares sobre arte mapuche desde la colección del MAPA. Publicación no. 9. Santiago: Museo de Arte Popular Americano MAPA, Facultad de Artes, Universidad de Chile, 2021.↩︎

María Alvarado. “Ñimin, Trarün, Wirin: Tres procedimientos expresivos en el universo textil mapuche.” Lengua y Literatura Mapuche 6 (1994): 9–14. Temuco: Universidad de La Frontera.↩︎

Angélica Willson. Textilería mapuche, arte de mujeres. Santiago: Ediciones CEDEM – Colección Artes y Oficios, 1992.↩︎

Portal de Contenidos Epewtun. Epewtun. 2024. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://www.epewtun.cl/.↩︎