Published September 2025 as part of the proceedings of the first Alpaca conference on Algorithmic Patterns in the Creative Arts, according to the Creative Commons Attribution license. Copyright remains with the authors.

doi:10.5281/zenodo.17084398

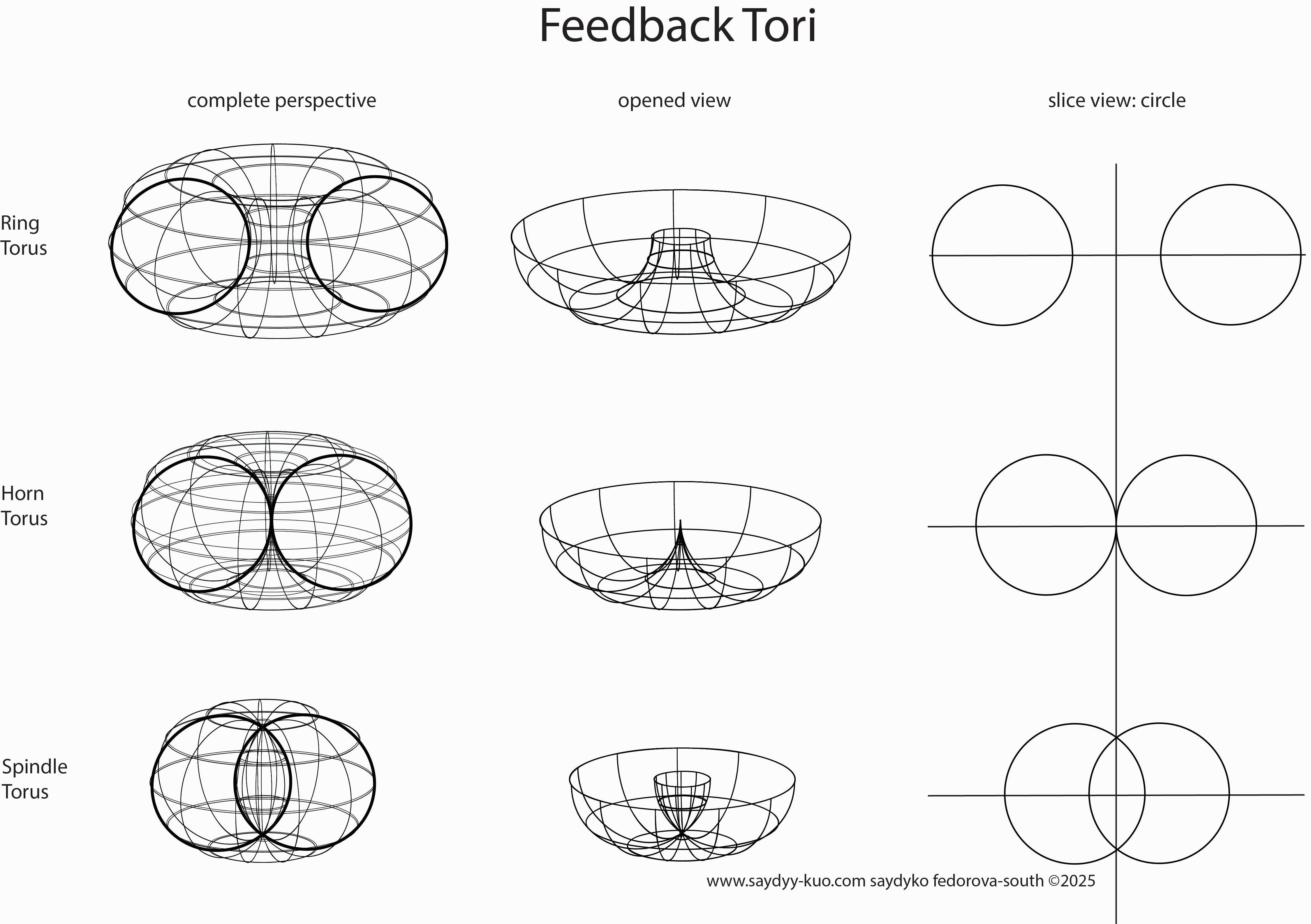

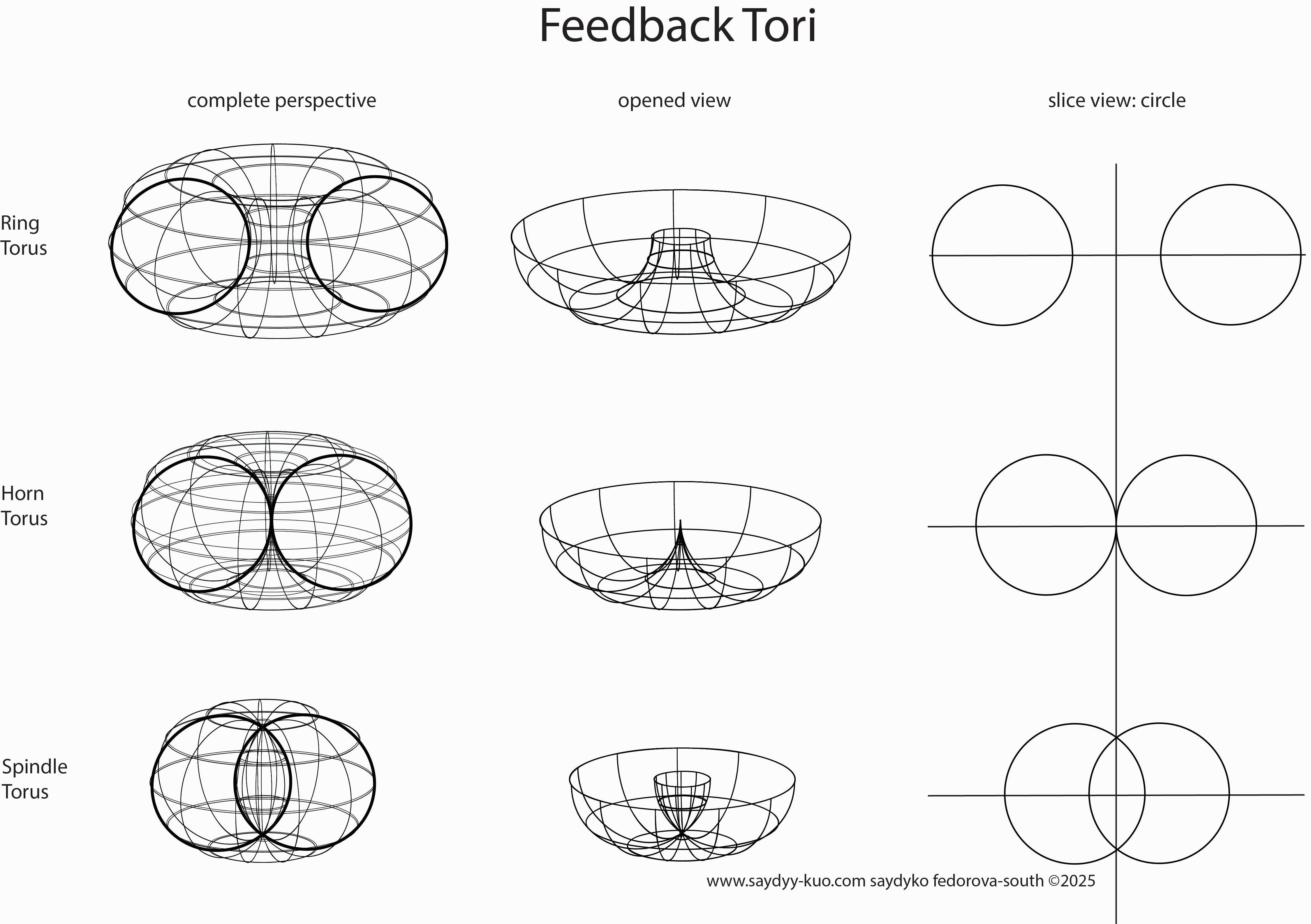

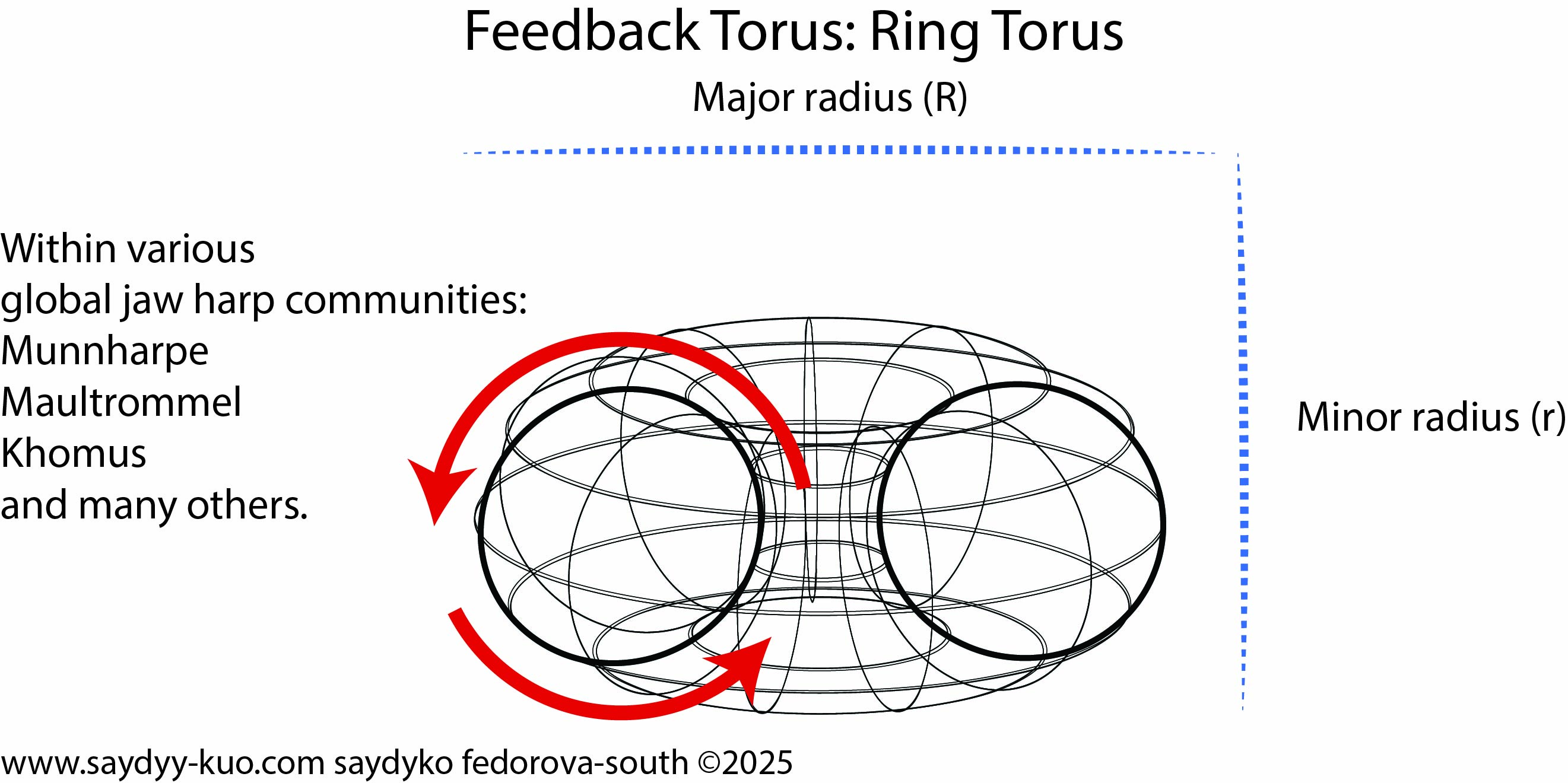

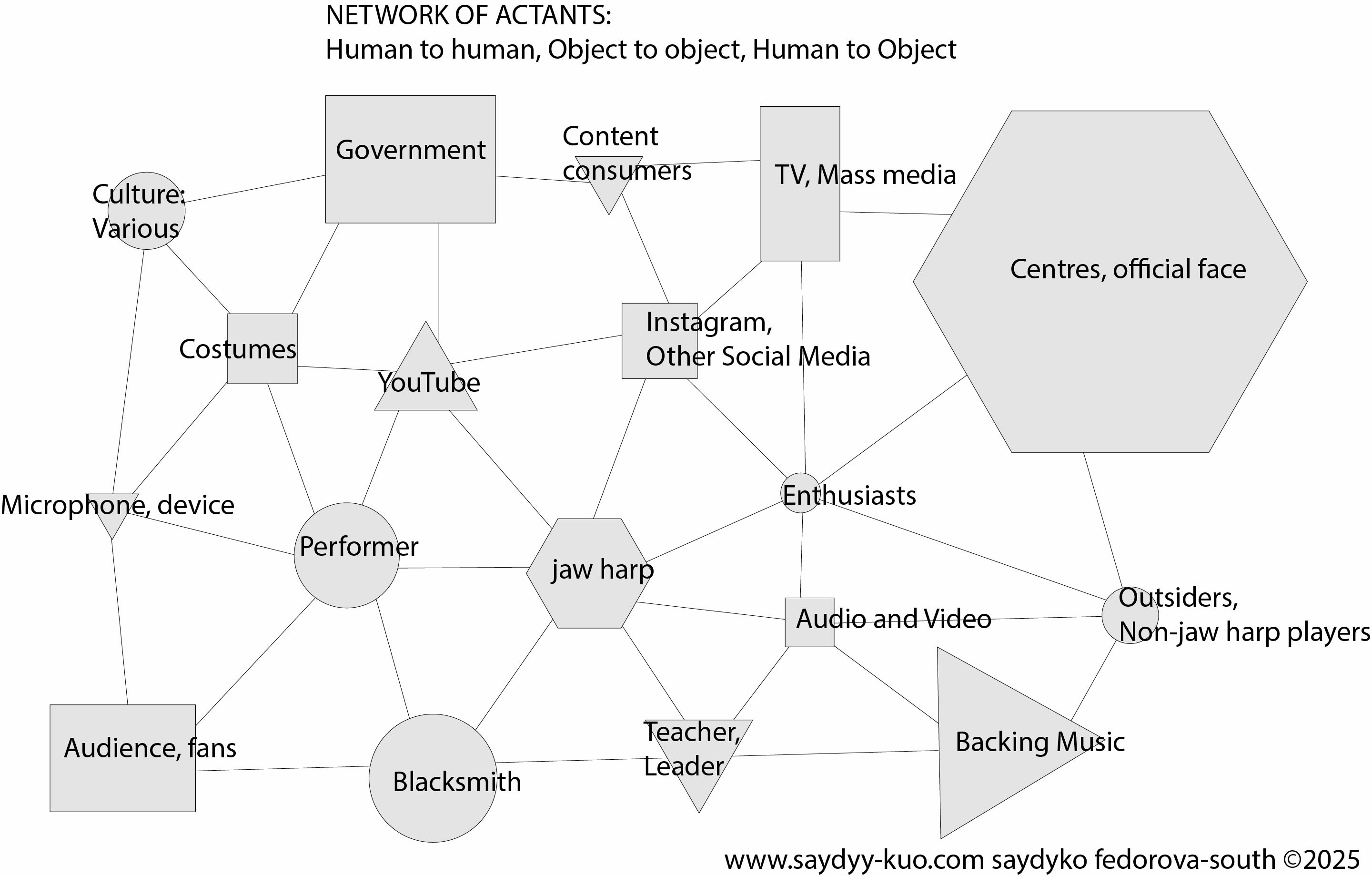

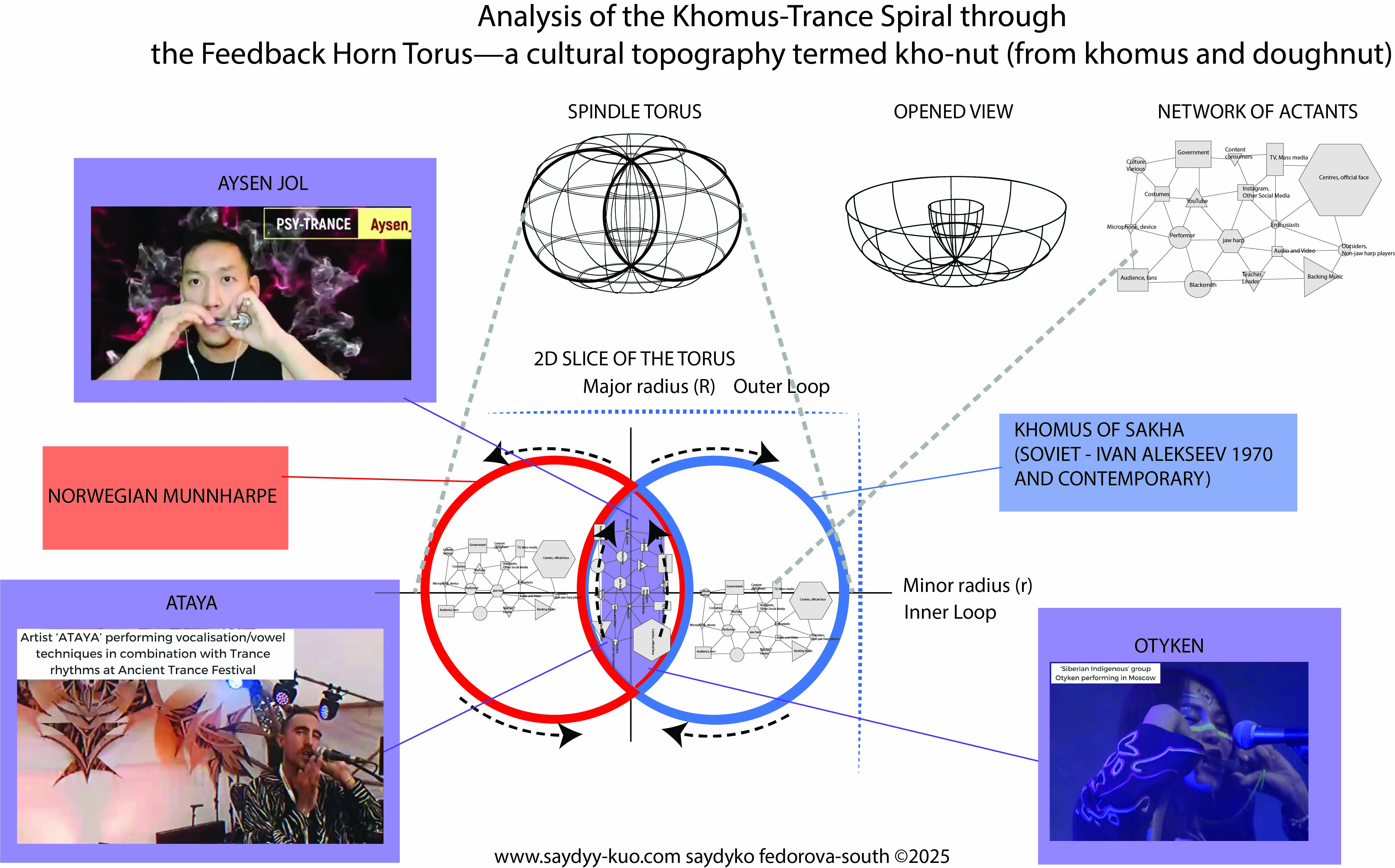

Traditional models of cultural diffusion cannot explain reciprocal exchanges in globalised music. This paper proposes the Feedback Horn Torus (Figure 1.1)—a cultural topography termed kho-nut (from khomus and doughnut). It models how cultural innovations adapt abroad, often digitally, then re-integrate into source cultures in transformative cycles. Depending on the density of jaw harp communities, the shape shifts from Ring Torus to Horn Torus, intersecting as a Feedback Spindle Torus. Unlike linear diffusion, loops, or spirals, it maps developmental journeys shaped by human and non-human actants (Latour 2005)1. This study introduces Global Jaw Harp Notation (GJHN), evidencing these stages.

In today’s era of digital globalisation, musical traditions travel and transform with unprecedented speed, moving beyond models of cultural influence that imply a simple, linear flow. The global jaw harp network illustrates a more complex dynamic: not diffusion, but reciprocal and evolving exchange.

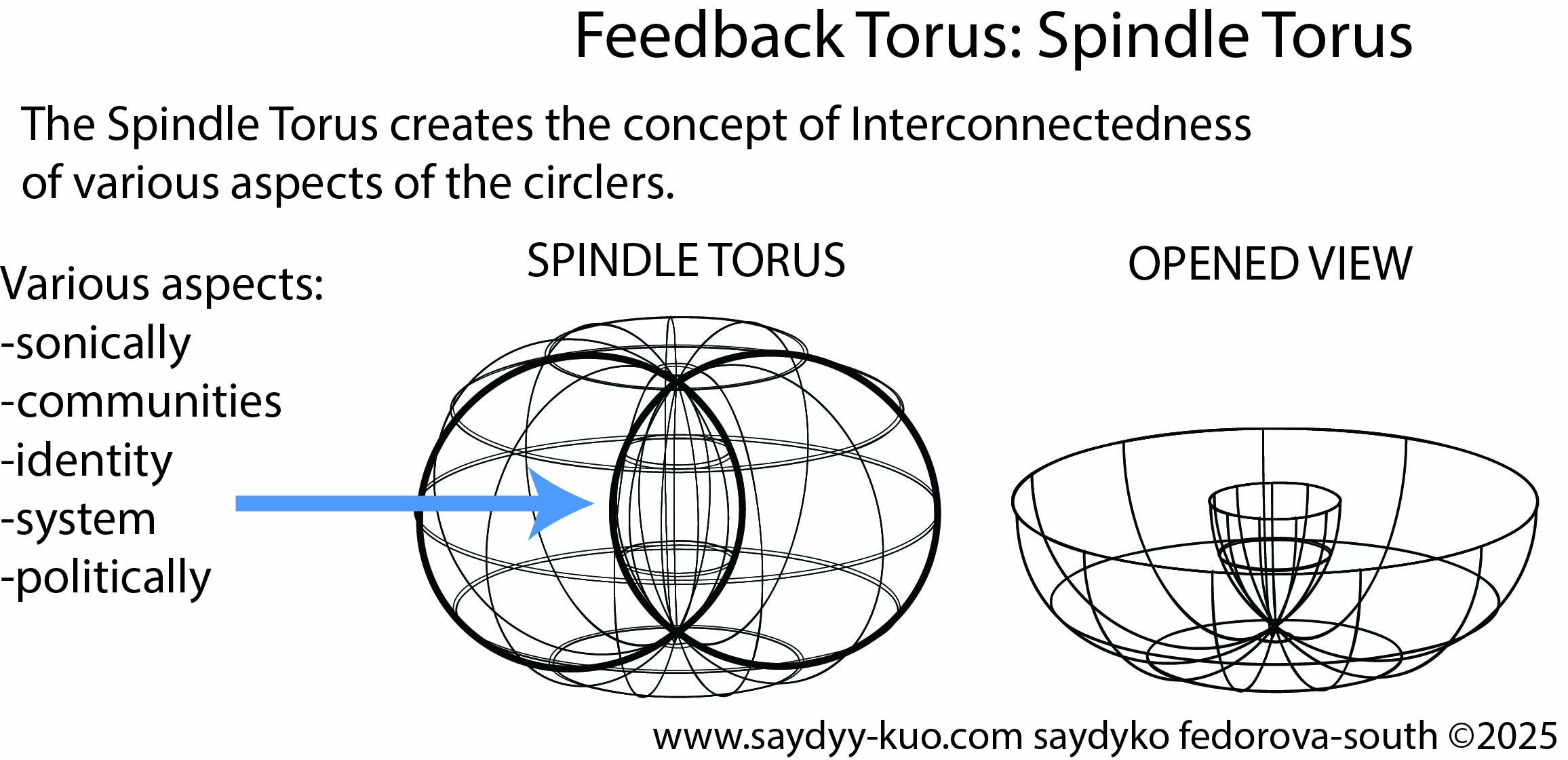

This paper proposes the concept of the Feedback Horn Torus to describe this process. It is a cyclical system in which a cultural innovation is globally adapted, technologically mediated, and reintegrated into its source culture. Momentum within this 3D cycle (Figure 1.2) is often amplified when participants, inspired by the jaw harp’s new visibility, uncover dormant traditions within their own heritage. Such local ‘actants’ enable a deeper and more transformative adoption of globalised practices.

The contemporary cycle begins with the Sakha khomus of Northeastern Siberia. A cultural revival there generated new playing techniques and meanings that became central to a global network, extending even into electronic music. These innovations spread widely, translated by diverse actors—musicians and enthusiasts across the USSR, Europe, Southeast Asia, the Americas, and through digital platforms—and later returned to shape a new generation of Sakha players. This paper defines the Feedback Horn Torus and traces one complete cycle, offering a more nuanced model for cultural influence in the 21st century.

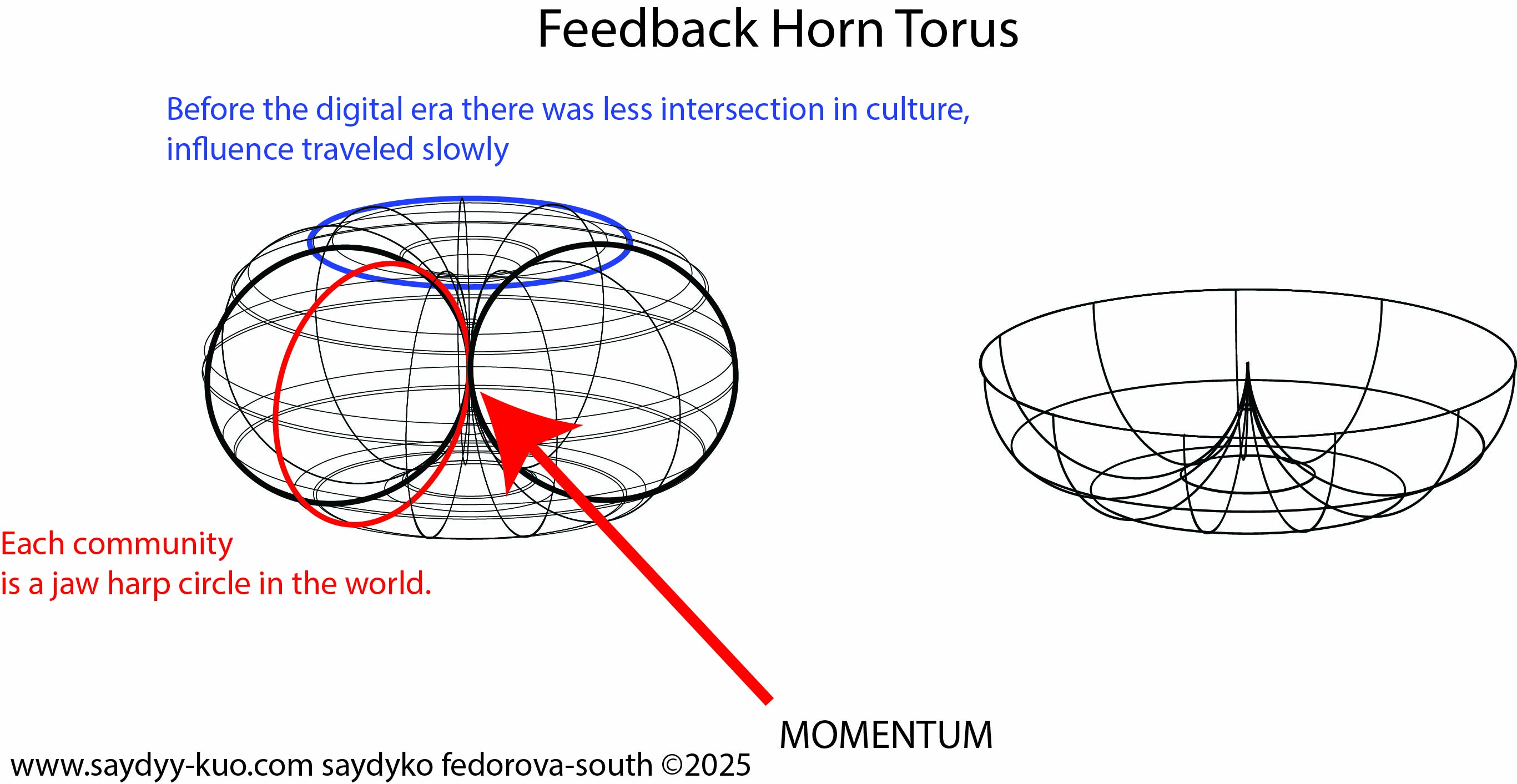

The Feedback Horn Torus is a model for cyclical and transformative cultural exchange in a globalised, digitally connected world. Unlike the linear model of cultural diffusion (Figure 1.3), where traits move one way from source to recipient, the Feedback Torus (Figure 1.4) traces how influences travel outward, transform, and return to their origin to spark new change.

Figure 1.3. Definition of cultural diffusion. Cambridge dictionary2. Accessed 21 August 2025.

Each circle—Minor radius ( r )—within the torus represents a global jaw harp community—Munnharpe, Khomus, Dan Moi and many others—arranged along the torus’ major radius ( R ). The mechanism (Figure 1.4) unfolds in four stages:

Innovation – A cultural group generates new techniques or meanings around an artefact (e.g., Sakha khomus).

Adoption & Adaptation – Other groups adapt the innovation, blending it with their own practices (labelled “momentum”).

Mediation & Dissemination – Adapted forms circulate locally and digitally, entering a globalised pool of ideas (Figure 1.5).

Re-integration – The origin culture, often its recent generation, encounters these mediated forms and re-integrates them, sparking new cycles of innovation.

At the intersection of circles, the model forms a Spindle Torus (Figure 1.5), symbolising convergence in the global era.

Influence varies across time and domains—sonic, communal, political, and both tangible and intangible. The khomus provides a case study of these dynamics. Importantly, the outer “red arrow” (Figure 1.4) completing the cycle reflects political structures: while recipients worldwide adopt the jaw harp out of curiosity, love, and passion, they often overlook the ideological frameworks shaping their participation. When influences return, younger generations (not always) at the origin usually embrace them, though not always organically; integration often demands conformity to local systems and expectations.

Thus, the Feedback Horn Torus illustrates cultural influence not as a linear flow but as a transformative, multi-scalar cycle of innovation, mediation, and re-integration.

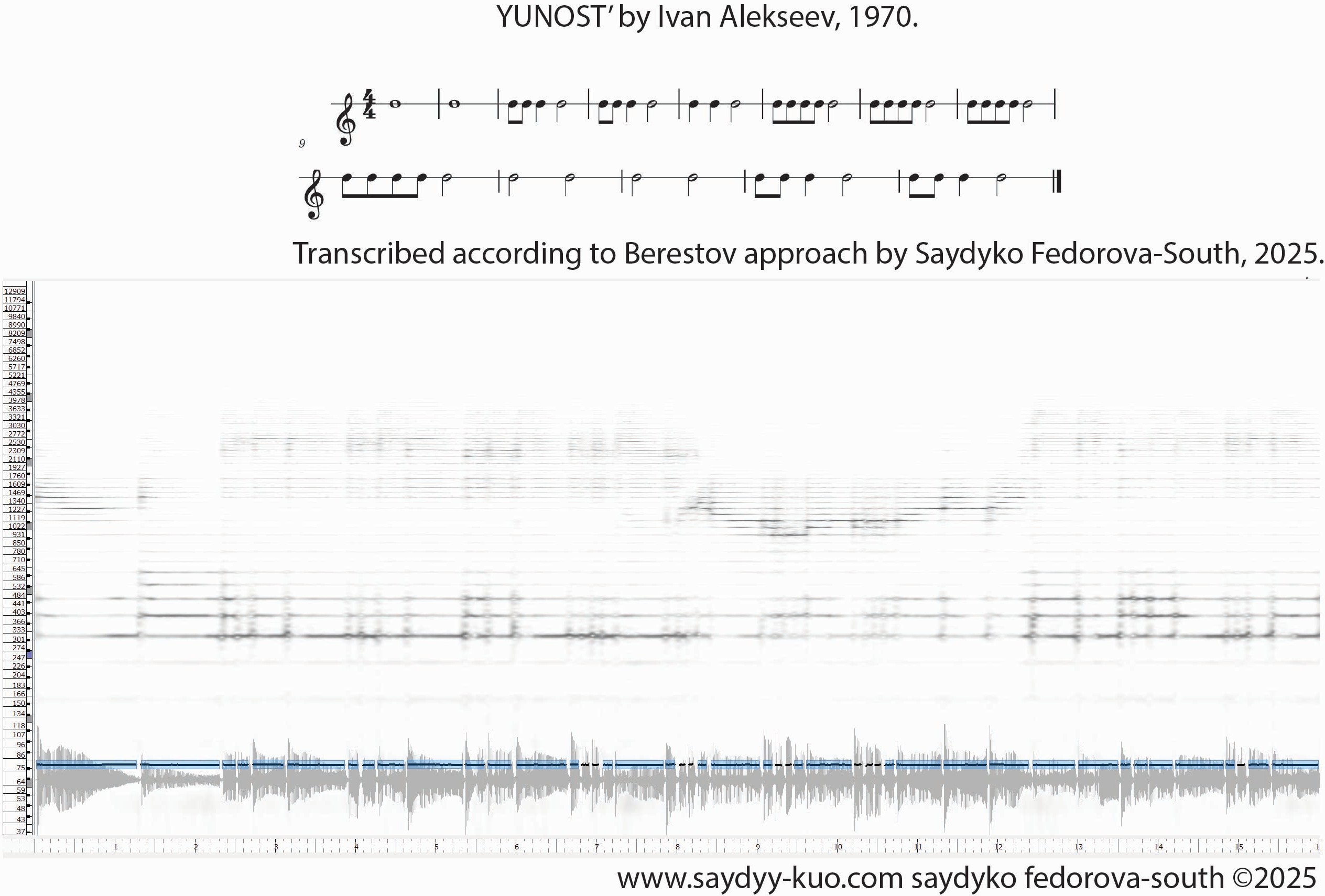

Analysing the musical evidence produced by the Feedback Horn Torus requires a new descriptive tool. Existing systems, such as staff notation, are inadequate as they primarily capture pitch and rhythm, failing to represent the timbral, phonetic, and overtone qualities central to jaw harp performance, particularly the influential Sakha techniques (Figure 2.1).

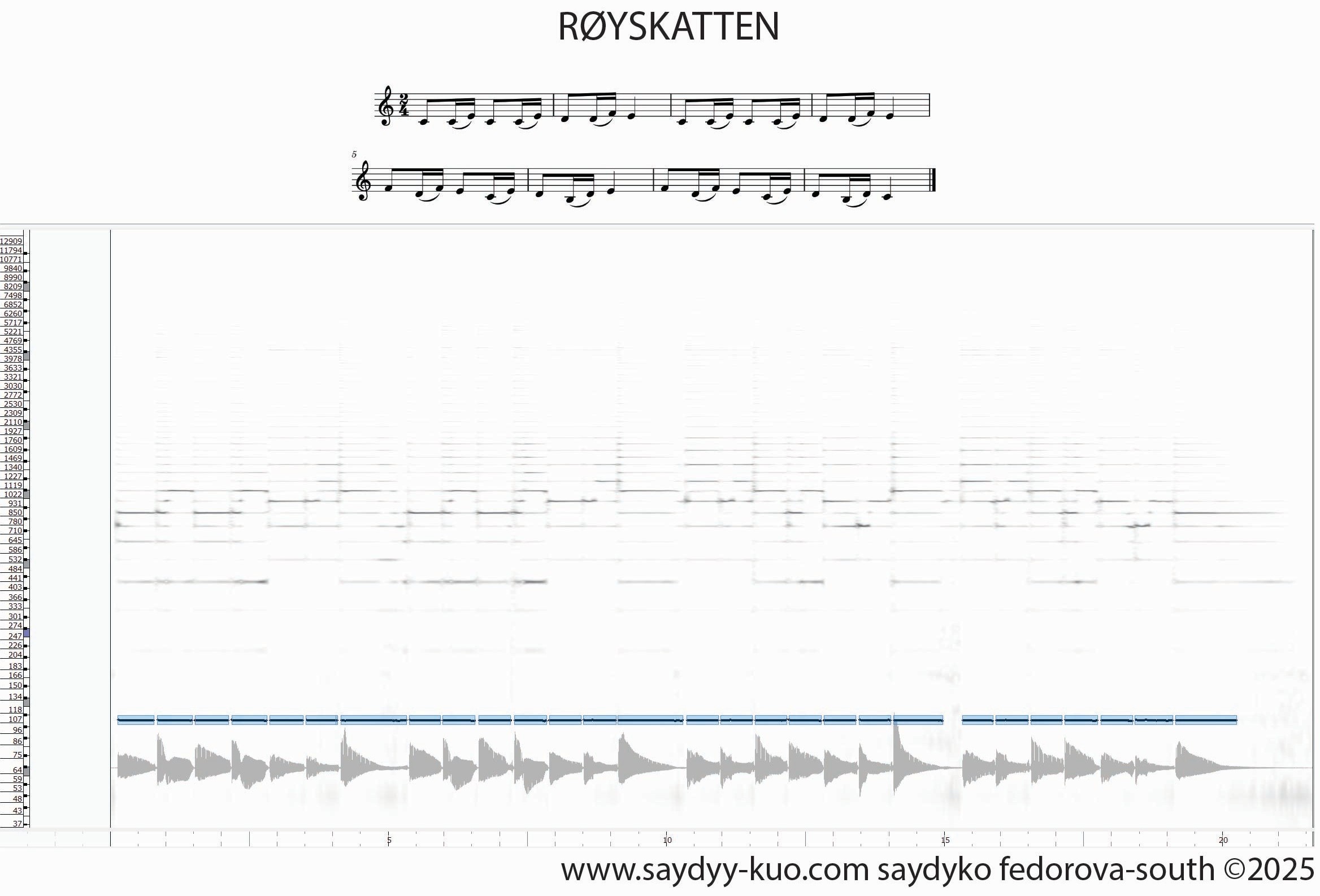

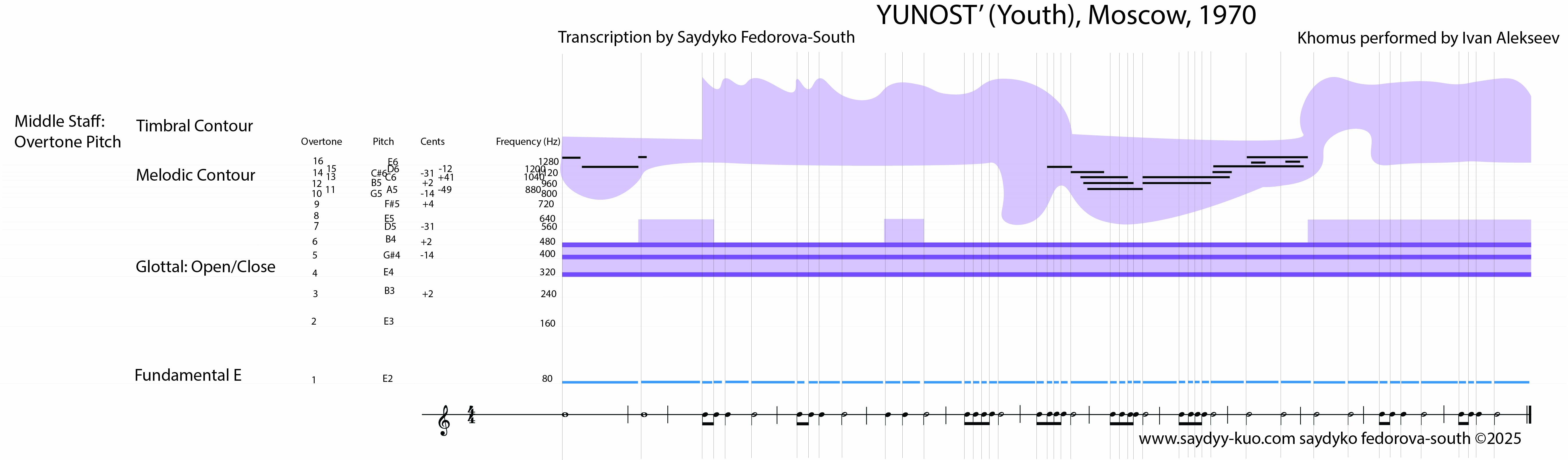

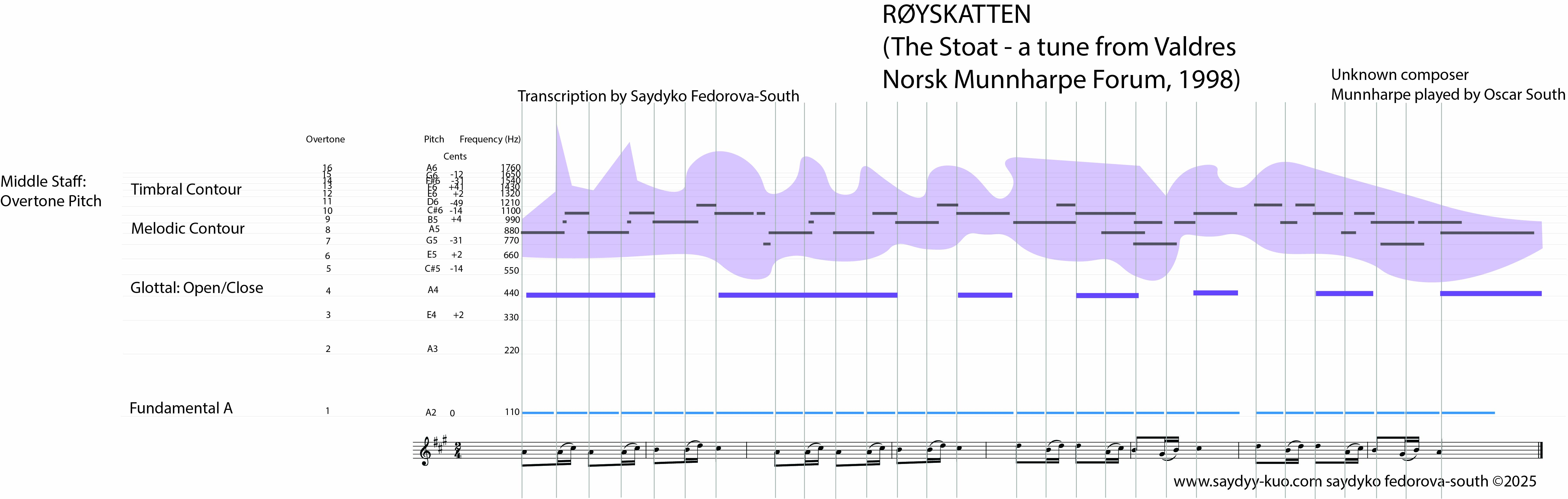

For example, the screenshot of Ivan Alekseev’s track (Figure 2.1) shows a spectrogram in Tony software alongside staff notation for khomus developed by Nikolay Berestov (2000)3. This system transcribes rhythm but omits notes, limiting analytical value. Another approach, developed by the Norsk Munnharpe Forum first published in 2007 with second revised edition 2011.4 (Figure 2.2), indicates both rhythm and pitch. However, it is transposing score, resembling clarinet notation, and therefore misrepresents the jaw harp’s overtone-based logic.

These limitations highlight the need for a descriptive system tailored to cross-cultural jaw harp sound analysis. To address this, I developed the Global Jaw Harp Notation (GJHN). The GJHN synthesises elements of earlier ethnomusicological methods—spectrogram-based analysis and staff notation—while adding missing layers specific to timbre, overtone articulation, and phonetic shaping.

Jaw harp sound consists of a fundamental pitch and strong overtones, often allowing perception of multiple simultaneous sounds. Overtones are partials forming a harmonic series above the fundamental, with frequencies that are integer multiples, creating intervals such as octaves, fifths, and thirds (Sundberg and Hefele 2021)5. These partials shape the timbre or vocal colour. Similar to overtone singing, where vocal cavities amplify selected harmonics, the jaw harp’s metal reed produces a drone while the player’s mouth acts as a resonator, enhancing specific overtones. However, dedicated research is needed to explore jaw harp acoustics, as overtone singing primarily concerns human voice production.

A useful comparison is Myers and Neumann’s Interactive Digital Transcription and Analysis Platform (IDTAP) for Indian melodic traditions. Inspired by Killick’s Global Notation (2020)6 and Seeger’s melograph (1958)7, IDTAP was developed at the University of California, Santa Cruz (2023)8. Myers and Neumann (2025)9 argue that while Killick’s framework offers a broad cross-cultural approach, it generalises too widely. Western staff notation and MIDI, they note, inadequately capture microtonal pitch, flexible intonation, and rhythmic nuance. IDTAP therefore goes further, prioritising idiomatic precision—the faithful representation of subtle musical features unique to a tradition—and integrating interactive computational tools for transcription, annotation, and corpus-building.

Similarly, the GJHN extends Killick’s principles but adapts them to the sonic specificity of jaw harp music. It models resonance filters, overtone emphasis, timbral contours, and spectral transformations, paralleling IDTAP’s “trajectories” that map archetypal melodic paths beyond fixed pitches.

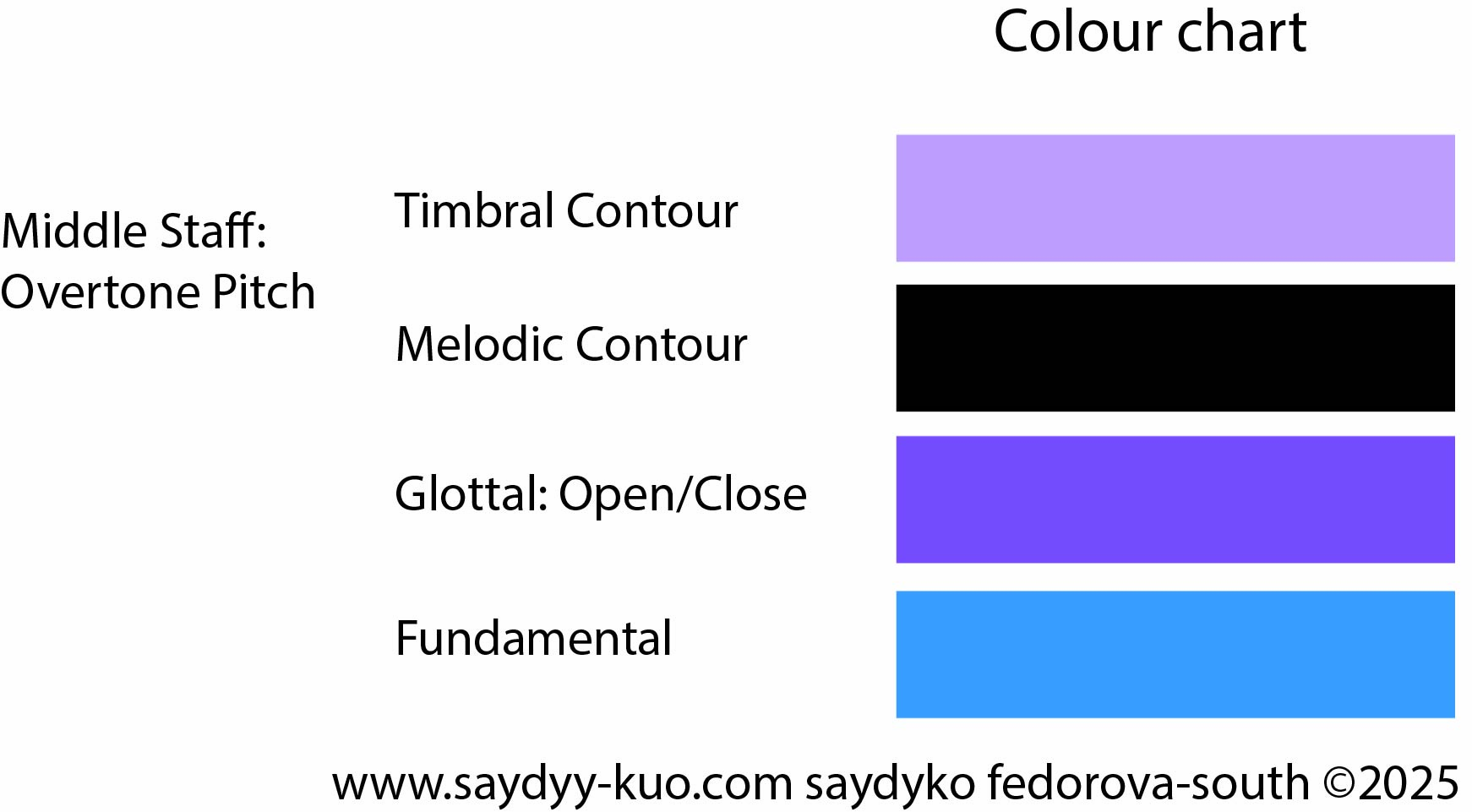

As detailed in Figure 2.2, the GJHN includes:

Middle staff: overtone pitch

Figures 2.3 and 2.4 show example transcriptions of Alekseev’s Younost’ (1970) and the Norwegian Røyskatten (1998, 2007, 2011, 2019). The Norwegian example demonstrates precise open/close glottal control, producing intended melody visible as black “melodic contour” lines. By contrast, Sakha khomus style maintains an open glottis, favouring rhythmic drive and a visible “timbral contour” over melody.

Through its multi-layered scores, the GJHN provides a comprehensive representation of performance, enabling detailed comparative analysis of how jaw harp techniques are adopted, transformed, and re-integrated across cultures.

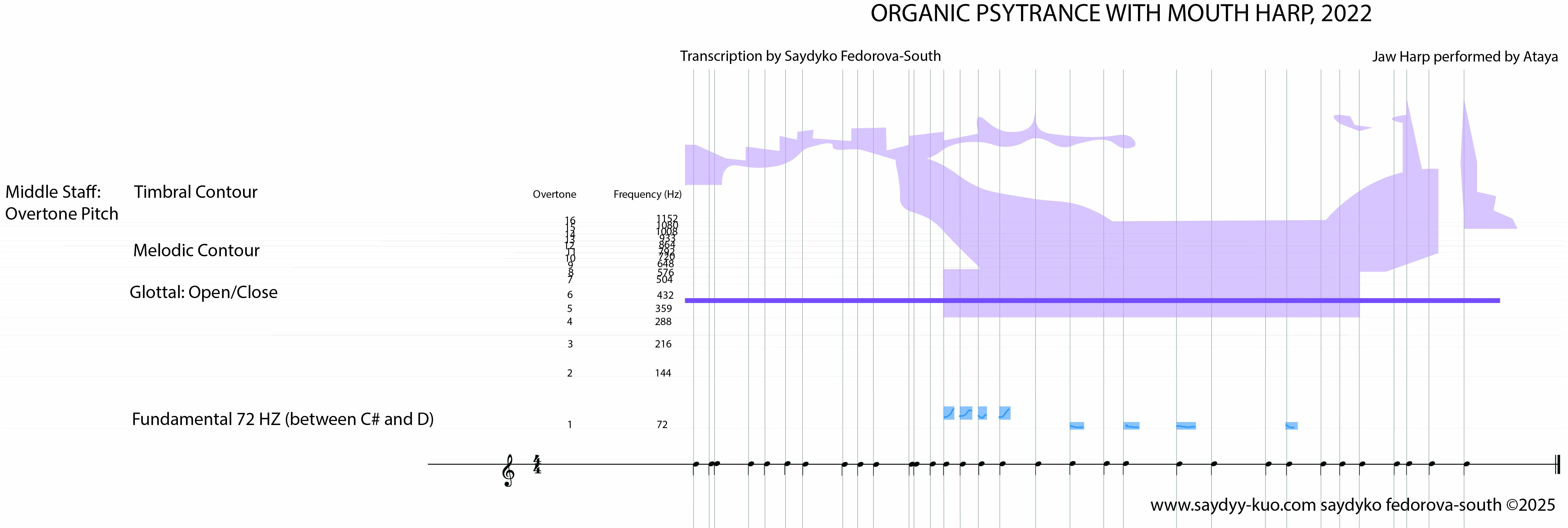

Innovations within the Sakha khomus circle illustrate how global jaw harp practices circulate through the Feedback Horn Torus. These innovations, when adopted elsewhere, often transform into new sonic expressions. A notable example is Ataya’s Organic Psytrance with Mouth Harp (2022) (Figure 3.1). His playing reflects adaptation and adoption within the globalised spindle torus (Figure 1.1).

Figure 3.1: Video - Ataya | Organic Psytrance with Mouth Harp, 2022 10Using the GJHN (Figure 3.2), Ataya’s transcription reveals a constant open-glottal technique—similar to Ivan Alekseev’s style—producing rhythmic and timbral contours without intended melody. External electronic beats, excluded from the transcription, intensify this trance aesthetic. Like Alekseev’s Youth track, the focus remains timbral and rhythmic, contrasting with Norwegian munnharpe music, which emphasises melodic contour.

The mediation and dissemination stage operates through non-human actants such as festivals, social media, and digital platforms. Actor-Network Theory a method of Latour, Callon, Law, developed in the 1980s 11 helps explain these dynamics (Figure 3.3). I first encountered Ataya through the Ancient Trance Festival 2023 and later via YouTube recommendations, demonstrating how algorithms and networks co-produce visibility and circulation.

Re-integration occurs when the recent generation of Sakha players adopt globally mediated forms as novelties within their own culture. For example, Aysen Jol blends khomus with psytechno (Figure 3.4), drawing from global electronic libraries (interview, 2025). Similarly, Siberian groups such as Otyken (Figure 3.5) integrate global aesthetics, styles, and industry practices into their music. These examples illustrate the cycle’s return: external influences, mediated through festivals and platforms, reintegrate into Sakha culture, sparking new hybrid forms.

Figure 3.4 Aysen Jol.”Khomus s psychodelicheskoi muzykoi - khomus with Psy trance music”, 2022. 12 Figure 3.5 Otyken, concert in Moscow, 2023. 13

The analysis of the khomus-trance spiral through the feedback horn torus (Figure 3.6) shows how as jaw harp communities and networks become more dense regionally and within the digital globalisation, the shape of the kho-nut becomes a spindle torus, where in the intescetion manifests a greater insection of communities and knowledge.

The Major radius is an outer loop - Global Circulation loop: (Sakha → festivals → global jaw harp scene → Sakha).

The Minor radius is an inner loop - Local Innovation Loop, a small internal circle within the home tradition: local sonic/technical innovations within each community (e.g. glottal technique, timbral play).

Centre of torus: reintegration of globalised elements back into Sakha practice (e.g. Aysen Jol blending psytechno).

Network actants:

Festivals (Ancient Trance Festival, etc.)

Social media platforms (YouTube, Instagram, TikTok)

Algorithms (recommendation systems)

Instruments/technology (khomus, synthesisers, recording tools).

Thus, the Khomus–Trance spiral demonstrates how global mediation reshapes sonic traditions. The GJHN makes these processes visible by mapping glottal use, timbral contours, and trajectories, enabling comparison across traditions. More broadly, this case exemplifies how cultural innovations circulate, transform, and return, generating new hybrid practices within a global feedback loop.

This paper has demonstrated the Feedback Horn Torus concept through a real case study and introduced a method for notating the diverse and complex sonic practices of cross-cultural jaw harps. By proposing a Global Jaw Harp Notation system (GJHN), I offer a framework for comparative analysis that builds on Killick’s earlier global notation. The GJHN system responds to the instrument’s dynamic and culturally specific articulations over the universality and broad symbolic abstractions of Global Notation. This opens possibilities for analysing, preserving, and comparing jaw harp traditions worldwide while recognising their plurality and ongoing transformations. Future research will utilise the GJHN system and the Feedback Horn Torus model in a large scale international field research study covering multiple global jaw harp communities, evaluating cultural, social, and political dimensions.

Saydyko Fedorova-South 14, member of UDAGAN 15 which performed at Algomech 2019, is currently pursuing her PhD in ethnomusicology 16. Her study looks at an indigenous musical instrument “khomus” (a jaw harp) and its social life, issues and opportunities presented by the jaw harp notation systems of various cultures for the purposes of broadly comprehensive analysis, and a phenomenon of reciprocal cross-cultural patterns of impact from ‘feedback horn torus’ of influence in khomus/jaw harp related societies. The pattern below (Figure A) is one of her artistic illustration was for UDAGAN’s music video “Snow Fox” 2021. All digital diagrams for the paper are produced by Saydyko Fedorova-South (r) 2025.

Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social : An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Incorporated. Accessed August 21, 2025. ProQuest Ebook Central.↩︎

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/cultural-diffusion↩︎

Berestov, Nikolay. 2000. Khrestomatiya dlya khomusa. Yakutsk↩︎

Søum,Veronika and Folkestad,Bernhard. 2019. Munnharpespel enkelt instruksjonshefte. Norsk Munnharpe Forum. Kongsberg / Horten.↩︎

Sundberg, Johan, Björn Lindblom, and Anna-Maria Hefele. 2021. “One Singer, Two Voices.” Acoustics Today, Spring: 44–53. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357809775_One_Singer_Two_Voices. Accessed 10 August 2025.↩︎

Killick, Andrew.2020. “Global Notation as a Tool for Cross-Cultural and Comparative MusicAnalysis.” Analytical Approaches to World Music 8(2): 235–79.↩︎

Seeger, Charles. 1958. “Prescriptive and Descriptive Music-Writing.” The Musical Quarterly 44 (2): 184–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/mq/XLIV.2.184.↩︎

Neuman, Dard, and Jonathan B. Myers. 2024. “The Interactive Digital Transcription and Analysis Platform (IDTAP): Enabling the Computational and Heuristic Analysis of Sound, Music, and the Social.” OSF Preprints, 11 April. doi:10.31219/osf.io/jx3pk.↩︎

Myers, Jonathan B., and Dard Neuman. 2025. “Beyond Notation: A Digital Platform for Transcribing and Analyzing Oral Melodic Traditions.” OSF Preprints, 9 July. doi:10.31219/osf.io/4a65s_v1.↩︎

Ataya. 2022. Organic Psytrance with Mouth Harp [video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/o10Afkfn4gs?si=tb0kCwrmxh-W-9kk&t=21. Accessed 20 August 2025.↩︎

Crawford, T. Hugh. 2020. “Actor-Network Theory.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature, 28 September. https://oxfordre.com/literature/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.001.0001/acrefore-9780190201098-e-965. Accessed 21 August 2025.↩︎

Jol, Aysen. 2022. Psytechno Khomus Performance [video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ByRK1LvomsI. Accessed 20 August 2025.↩︎

OTYKEN Official Full Concert - Pulse of the Earth (Live at Moscow, Base 2023) https://youtu.be/SyjGsk41zmU?si=NK8veu6r4a9AYAaF&t=2356. Accessed 20 August 2025.↩︎

www.saydyy-kuo.com↩︎

www.UDAGANuniverse.com↩︎

University of Sheffield↩︎