Published September 2025 as part of the proceedings of the first Alpaca conference on Algorithmic Patterns in the Creative Arts, according to the Creative Commons Attribution license. Copyright remains with the authors.

doi:10.5281/zenodo.17084400

I am a multimedia artist, working mainly with weaving and performance.

For the past six years, I’ve been researching the story of my grandfather, Kazimierz Gaca, a Polish resistance fighter during the Second World War who worked with the Enigma machine.

This personal history has led me to create woven pieces on a digital Jacquard loom, where I hide codes inspired by encrypted wartime messages, drawing parallels between the loom and the Enigma machine, both foundational to the development of computers and binary systems.

This research also gave rise to a collaborative experimental film performance, which was shown at the La Alternativa festival at the CCCB in Barcelona.

In 2023, the project was exhibited for three months at the Centre Pompidou in Metz, in the Capsule of the Museum, and was also presented at the Octobre Numérique festival in Arles.

I was also part of a collective exhibition in 2025 about Textile, Resistance and Performance called “Under the Weaver’s hands” at the Kunsthalle of Trier in Germany, curated by Çağla Erdemir.

The intersection of textiles and cryptography and steganography are old, as well as emerging fields of study that bridges art, technology, and secrecy. The ability of textiles to encode messages, whether through patterns, colors, or structural variations, has historical precedents in resistance movements and military intelligence.

This research is focused on some of my textiles, and on the creation of a personal alphabet. These codes in the weaving codes are weaved on manual and digital looms.

The goal is to create encrypted messages, either by creating a program to use on a digital loom, and which can be transcribed into a sound language as well, and into an image, thanks to steganography or making a loom myself through cryptographic systems.

There are different ways to encrypt messages. Cryptology is the science studying secret messages.

Cryptography is the act of writing secret messages, we hide messages that can only be read by the people that have the right key to do so. “It comes from the ancient greek”kruptos” which means “hidden”.” 1.

Steganography is meant not to be visible and hides a content in an image or a sound. “It comes from”Steganos”, which means “airtight” in greek. For instance, the technic of the invisible ink is a known and old steganography technic. Nowadays, there are “digital techniques that made numerous steganographic tools available to the general public (PixelKnot, Steghide, Invisible Secret 4, etc.). (…) For investigations into paedophile networks, security agencies have had to develop new decryption techniques. This is referred to as steganalysis.”2.

Historically, textiles have been employed to convey encoded messages, often in contexts of resistance or subversion.

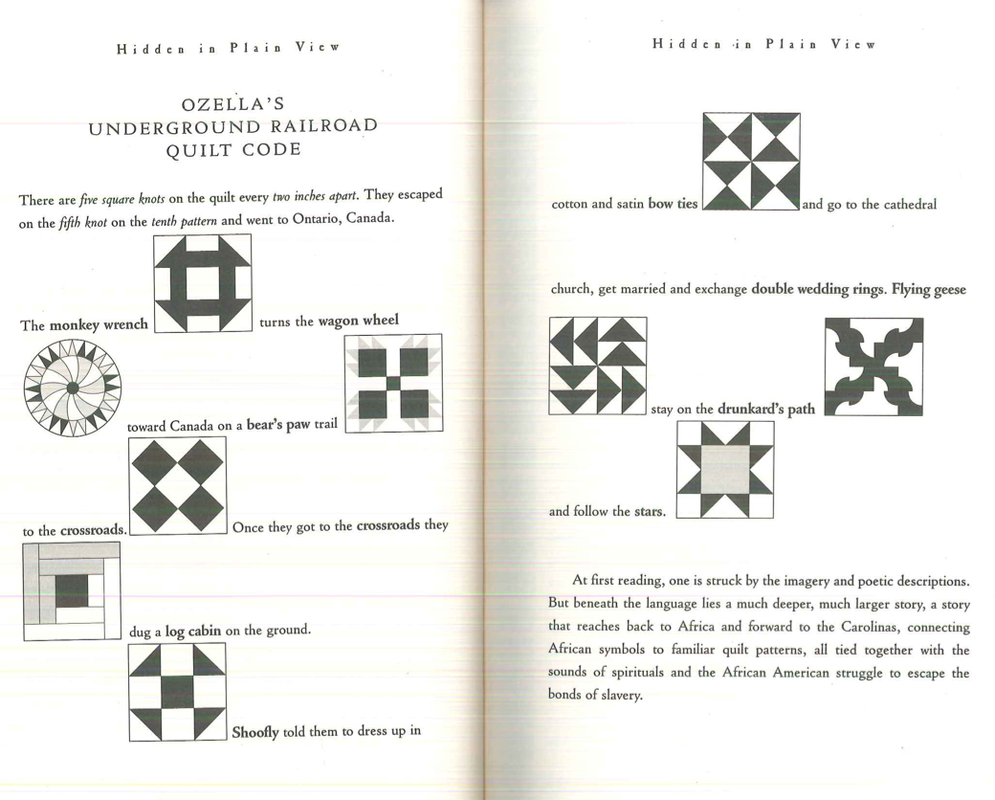

For example, during the 19th-century abolitionist movement, quilts served as communicative tools along the Underground Railroad, guiding enslaved individuals to safety through specific patterns and symbols. Scholars such as Tobin (2019) have explored how quilt codes functioned as visual ciphers, with distinct designs conveying navigational instructions.

In wartime, textiles were occasionally utilized to transmit secret messages. Embroidered symbols, knotted threads, or specific weaving techniques allowed critical information to be concealed in plain sight.

During World War II, some prisoners of war allegedly used textiles to encode intelligence, embedding data within fabric patterns that could evade detection. This innovative application of textile cryptography underscores the longstanding role of fabric as a medium for covert communication.

Modern textile artists and technologists have begun to explore these intersections by incorporating algorithms and programming into their textile designs.

The South-Corean artist Ham Kyungah used textile steganography in different embroidery works. In 2014-2015, in her serie of embroideries, she uses craft to communicate with artisans and factories from North Corea to cross censorship and direct messages to the workers.

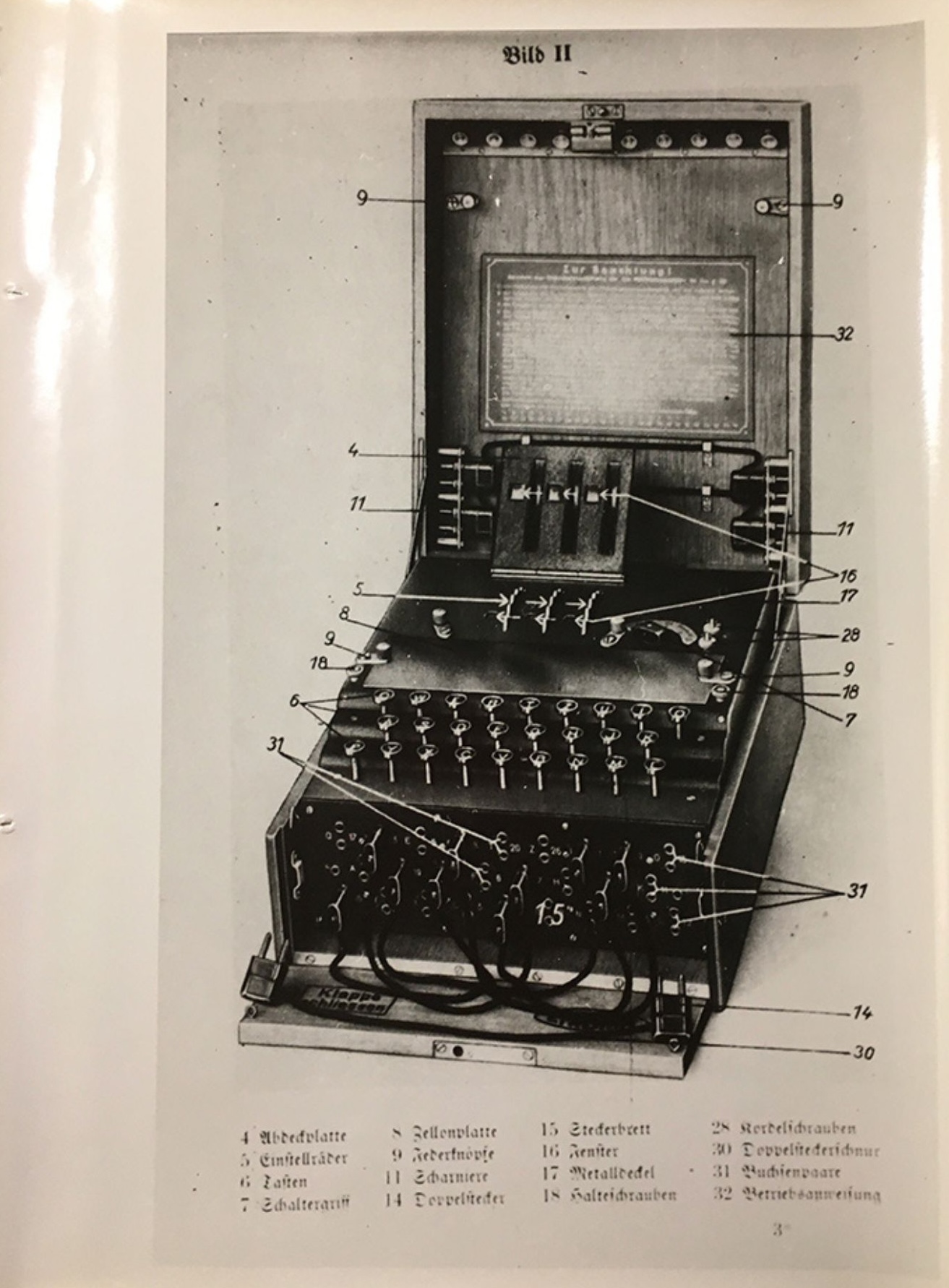

The Enigma machine, developed in the early 20th century, revolutionized cryptography with its complex rotor mechanisms capable of producing billions of cipher combinations.

Used extensively during World War II by the German military, its encryption system relied on structured sequences, rotor settings, and plugboard configurations to generate seemingly impenetrable codes.

Both weaving and cryptography depend on structured, sequential systems to produce outputs that appear random to an uninformed observer. In weaving, warp and weft threads interlace in specific, predefined patterns, much like the interaction of rotors within the Enigma machine.

Binary code can be translated into woven patterns, with the presence or absence of a thread representing binary values (1s and 0s). This innovative approach bridges traditional craft with digital technology, reflecting the binary logic underpinning devices like Enigma machines.

The message arrived with an indicator, and then the content of the message itself was shared. The indication was called a “key” by cryptologists. The key indicated the position of the rotors, with three letters.

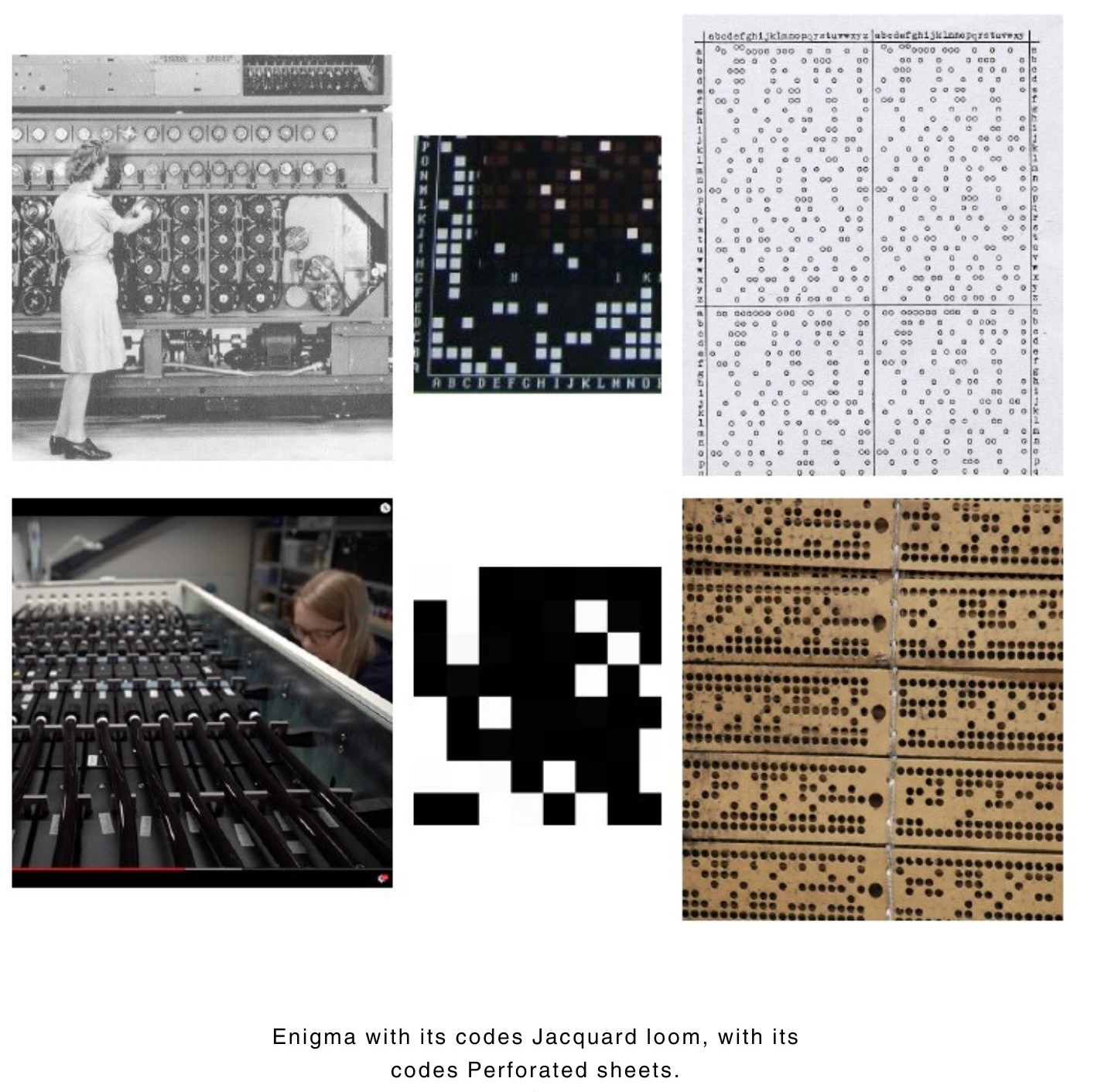

While the Germans were making decoding more and more difficult, the Poles made two other important advances to break the code. The other was established by the Polish mathematician Zygalski, who invented perforated sheets called “Zygalski sheets,” later called “Jeffreys sheets” when the English began to produce them at Blechley Park, led by the mathematician Alan Turing.

It is important to finally recognize nowadays that the Polish team cracked the code and then passed on the informations to the British.

In the sheets, they first manually punched what they called “females,” these are the indicators that are repeated in the coded text. On cardboard sheets, the alphabets were placed, repeated four times, and a hole was punched at each intersection where the “females” appeared.

At the end of the day, they would overlay all the sheets with the combinations to find where there were holes that matched and allow the rotor positions to be found. The structure of Zygalski’s sheets that my grand father was perforating manually with cutters are an important base for my symbols creation. This allowed each letter represented by a symbol to show the “key,” which is what indicates which letters appear to give us the clue to the code.

The principles behind the Enigma machine, pattern recognition, substitution ciphers, and modular encryption, bear striking similarities to textile design. Weaving, for example, involves interlacing threads in predetermined sequences to create intricate patterns. These sequences function analogously to encryption keys: altering the sequence transforms the resulting pattern, much like an encrypted message.

I started thinking of the Jacquard loom and the Enigma machine as being two similar machines, capable of encryption. The Jacquard loom does not have the purpose of encoding and decoding messages but I found similarities in its structures and origins. The use of Zygalski cards are inspired from any form of binary manual system, through punching cards.

The Enigma machine works in such a way that it is like a writing machine with two keyboards one which you type with and the other one with letter and lights that light up. When you type a letter, another one lights up, and every time you type the same letter, the one that lights up changes. This is due thanks to rotors, that have been added up throughout the evolutions of the different Enigmas. The rotors will change the letter combinations every time.

The “Bomba”, invented by the polish cryptologist Rejewski and implemented by Turing at Bletchley Park was used to find the positions of rotors. This was done in Bletchley park mainly thanks to women. “Joan Clarke, later Murray, was described as”one of several “men of the Professor type” to be a woman” on the higher echelons of the Enigma team.” 3.

Apart from showing “reproduced work gendered hierarchy that was happening at Bletchley Park, where women were realising more repetitive tasks than men” that Elsa Boyer highlights in her biography about Alan Turing, 4, it also shows the craft of repetition that was occurring.

If I want to use cryptography through weaving in the way that the Enigma machine is made, I have to invent a Jacquard loom machine.

I am in the process of thinking of what it could look like, which would make a pretty complex system to adjust both funcionalities in a certain way. I imagine a Jacquard loom, working either manually or digitally, with rotors added onto it to change the position of the threads while weaving. I started drawing what I imagined and I asked the AI image generator Midjourney to simulate what it could look like. For now the idea is there but not the complex realisation yet.

The Jacquard loom was patented in Lyon in 1801 by Joseph-Marie in Lyon and is the fruit of the work of numerous researchers. I got the chance to do a residency in what used to be his house, with the Textile Lab of Lyon.

It was the first programmable loom, the original one is very manual to use, due to its precision, and the weavings created are special pieces, as all the threads are mounted on the loom (by warping, a long and complex stage, where the weavers position the warp threads one by one on a warping machine and then on the beam).

I use different types of loom, but the one I’m most fond of is a Jacquard loom, updated today, because it allows me to represent pictorial illustrations, to let the trace and layers show through, and to show the materiality of our images.

Indeed, Jacquard is a technique that has revolutionized weaving, since it enables us to control all the warp threads (those meticulously mounted on the loom, a long-term task, both individual and collective). The results are pieces that could be said to control all the pixels of an image, a material image in this case.

It thus becomes one of the ancestors of the computer, and understanding how it works is akin to knowing the inner workings of our technologies.

To make a fabric with a pattern, the Jacquard loom gives the order for the warp threads to be raised according to indications given by cardboards. They translate the transposition of the pattern into a grid to determine where the intersections of the threads (the ligaments) are positioned.

Historically, cardboards were perforated and used by hand-held Jacquard looms. The preparation of these cards is often replaced by computer programs today.

I now mainly use a Jacquard loom which is both digital and manual, adapted to weavers that want to do the job of weaving themselves. With the digital Jacquard loom, here the binary symbols are made manually and then translated into coded programs and transferred it to the loom program itself.

The operations with the card are as follows:

The first cards were launched by a series of cards connected to each other that formed a continuous loop.

According to my personal research, in the Jacquard digital loom, can be found a similarity with the work of Enigma. My grand-father was punching the Zygalski sheets manually and it is an action I find myself doing now, to prepare weaving files (which are often digital nowadays).

The position of the rotor of the Enigma machine can be compared to the needle of the digital loom that catches the threads that go up or down. In the same way, the letter encoded with the Enigma machine can correspond to the “weave” used in the loom. Today, the perforated sheets of the loom are replaced by programs, and the Enigma codes are also encoded or decoded by programs.

It occurred that steganography was an easier way to hide text into my weavings, through changing the woven pixels of the “images” I weave.

I had to invent my own way to encode text through pattern making. I started trying out online platforms, but the results were too very connected to the screen, and I could control myself the “program” of the loom, so I decided to invent experimental and subjective ways.

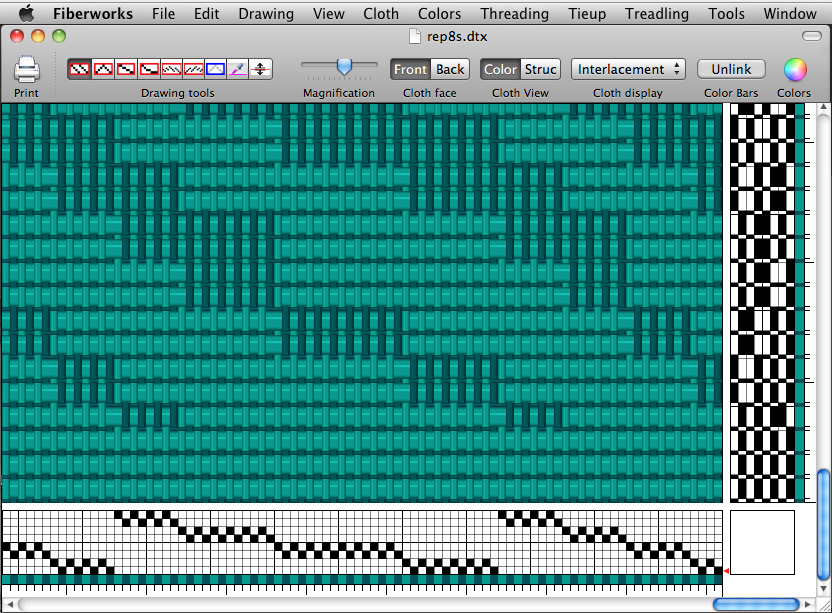

The Jacquard digital loom allows digital files to replace the numerous perforated sheets. Weaves are repeated lengthwise and widthwise, they determine the intersection of two threads at the time of weaving. Warp and weft threads cross.

The weaves that we introduce into the loom are read as a binary code, of 0 and 1 or of black and white squares. Weaves give a binary effect to the fabric.

They determine whether the heddle or needle lifts a warp thread or not. Weaves can have a warp effect or a weft effect. This gives the final fabric a heavy or light effect.

Beyond the known weaves of fabrics (twill, satin, etc.), invented motifs can be created thanks to the grid of the weave.

From there, in these weavings a language are created, that would translate a letter into a shape, a symbol to be represented.

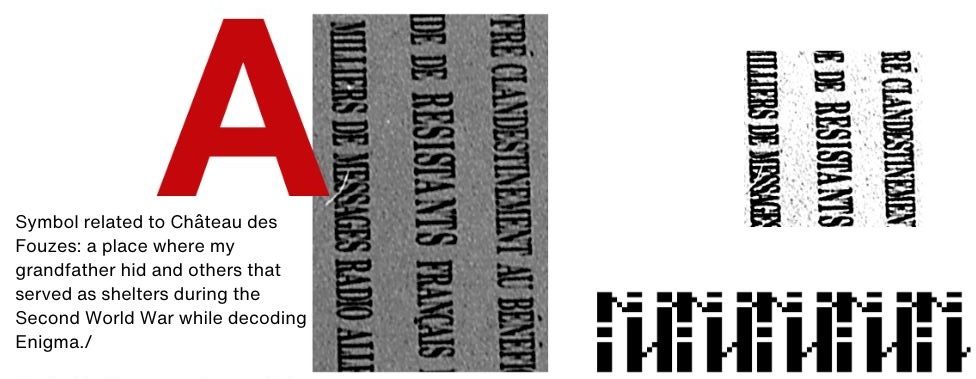

Each one comes from photos that represent resistance. Starting with some places where my grandfather Kazimierz Gaça was, and some that are related to the Second World War, to some that represent places of current struggle (such as the Zapatista snails in Chiapas, Mexico and the Zad, Zone to Defend of Notre Dame des Landes, in France).

Chateau des Fouzes : Extract from the plaque at the entrance to the Château des Fouzes in Uzès. This is where Kazimierz Gaça, as well as the other Polish, French and Spanish resistants took refuge to decode the German messages, which were received clandestinely in the basement, by radio. The analog picture I took is then pixelized and simplified to create a binary code, that can then be weaved, and that will let hide micro symbols into the structure itself of the weaving.

### C. The weavings

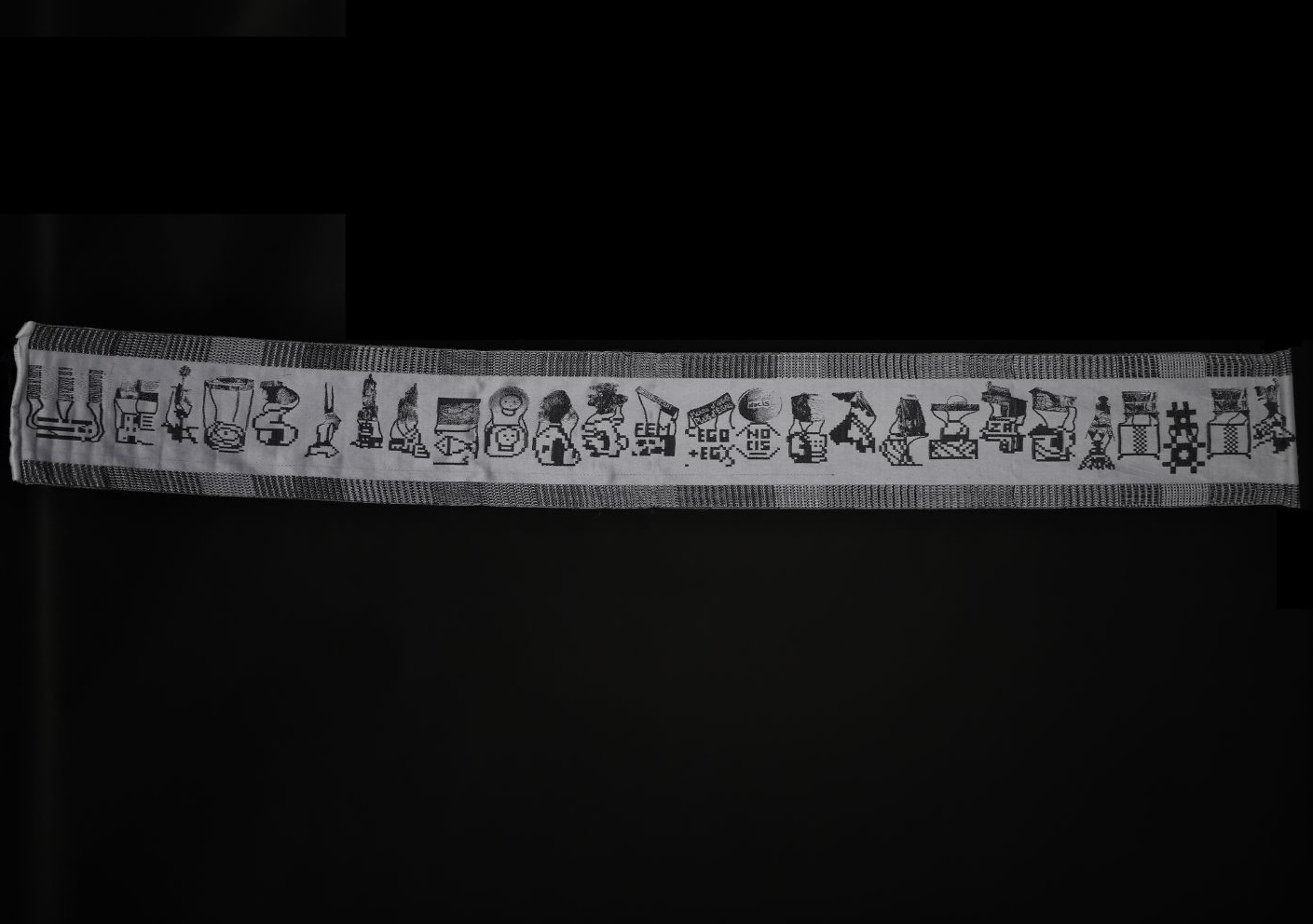

It is read horizontally and is divided into 26 parts, which are the 26 letters of the alphabet, represented by their symbol. This weaving is “the key”, to help the person that would have to decode a fabric, to decode it. It shows every letter of the alphabet, its macro version of the symbol, and its micro version, scaled as one by one pixel.

Above and below the fabric are two ribbons divided into 26 squares, filled with the corresponding symbol, repeating the ligaments, as at the end of the first fabric.

In the middle rectangle, the different symbols appear one by one, connected with their pixel representation (or binary code), to illustrate the invented code.

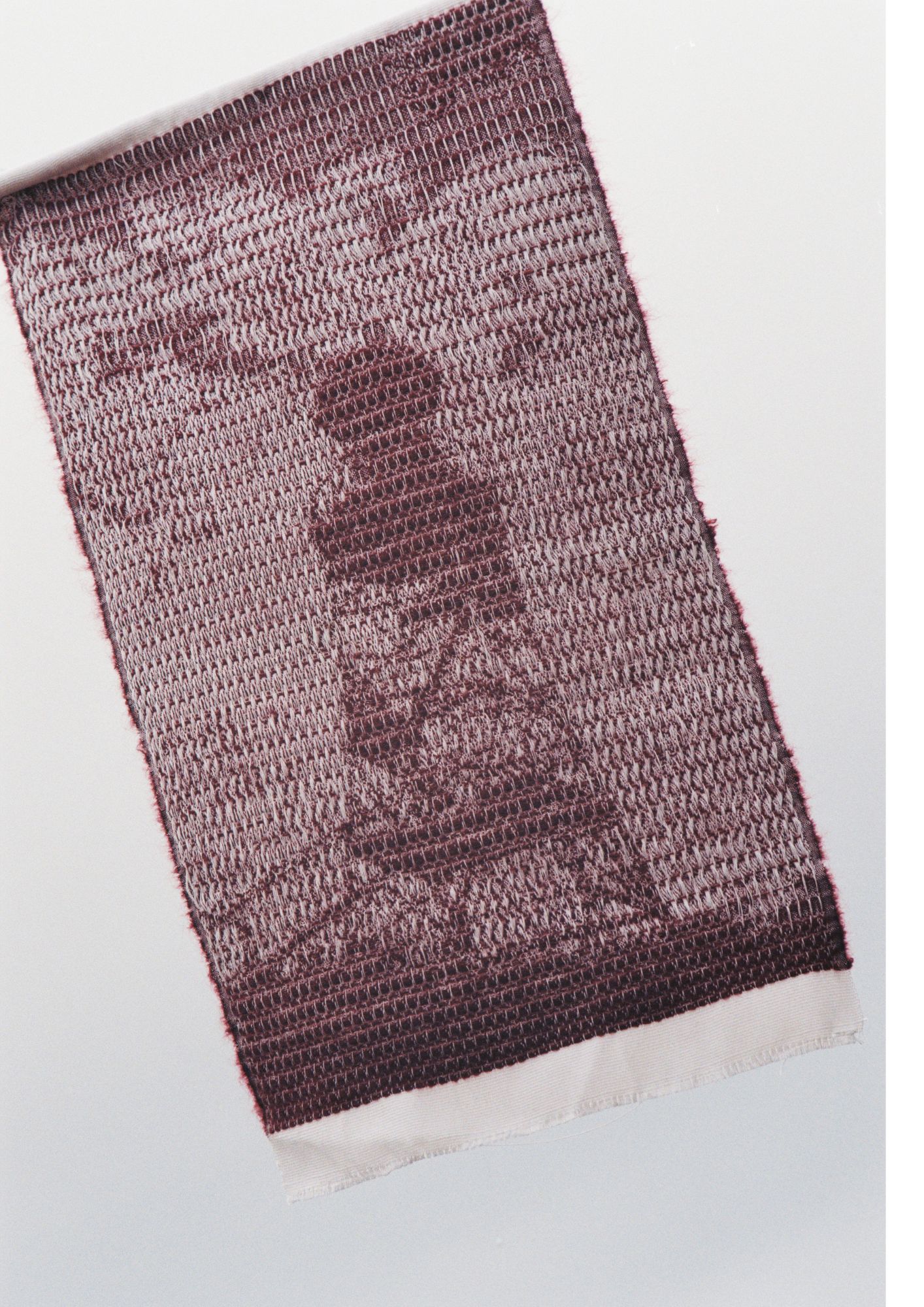

It represents hidden messages, inspired by steganography, within the symbol that corresponds to the letter “V”.

In this weave, the image and the contrasts of this image contain various symbols of the alphabet. The symbols used correspond to the letters “F”, “Q”, “R”, “O”, “Y”. These letters give a clue for decoding the message, as if it were “the key” to the

Enigma machine. The weaving “Alphabet” can be used to be able to decipher this weaving, as well as if the person that reads it knows about weaving and can transfer the patterns back into a grid, then the message can appear.

These letters are present in the title and the first line of the poem by Susan Saxe, an eco-feminist activist who was wanted by the FBI. These first lines are the following (For the FBI agent who, enquiring about a sister, asked “Who is in her network?”

This text is the response to an FBI agent, who asks her about a “sister” of hers, who is part of her collective. She answers him by showing how absurd his question was, asking herself metaphorically, for example, “what clandestine hand has written a secret message on the seed? Who has thought up the spider’s web and planned the grass’s strategy?”

This image, which represents the letter “V” of the alphabet, is the lighthouse of the Zad airport, converted into a place of struggle to observe from where the police could arrive (described in the alphabet).

The following is the trailer of the cinematic performance “De-Coded” by Bérénice Gaca Courtin and Eduardo Filippi with live music by Lea Eller, Opuku and Daniel Moreno Manzano. It was presented for the experimental cinema festival La Alternativa at the CCCB Museum in Barcelona in 2021.

“A session dedicated to celluloid and its constellation of extensions and aesthetic and creative possibilities, of course, but also ethical and political. World War II. A machine created to decipher encrypted Nazi messages. A group of Polish, French, English and Spanish resistance that aims to overcome the barrier of time and anticipate the end of the war by resonating with the codes that will give rise to the beginnings of the computer. An invisible beginning in which a family history once again reveals everything secret and hidden.”

The following videos come from the collective exhibition in 2025 about Textile, Resistance and Performance called “Under the Weaver’s hands” at the Kunsthalle of Trier in Germany, curated by Çağla Erdemir.

“With I would make my shuttles fly, Bérénice Gaça Courtin develops the multi-layered performance that began at the exhibition opening. At the intersection of textile art, technology, history and resistance, she weaves together fabric, sound, code, par- ticipation and speculative narrative into a temporary, multi-dimensional network that unfolds across past, present and future. At the center of the work is Mokoshe, a non-binary textile hacker and alter ego of the artist, who speaks as a voice of the present. Mokoshe communicates via encrypted fabric with two other characters: Mokosh, an ancient Slavic mother-goddess of weaving, and Aëlle, a hybrid creature between man and axolotl from a speculative future. The video accompanying the performance is a 3D version of Mokosh, created with 3D artist Jérôme Cortie. The tapestry created during the performance, by the hands of the artist and his performative figure Mokoshe, was presented at the Kunsthalle Trier at the end of the exhibition. It remains a woven archive, a visible trace of collective memory, a textile legacy of the evening.”

Text by Çağla Erdemir.

Performances: Bérénice Gaça Courtin with Adrian Rehm Special thanks to Ketut for his contribution to the sound design and Jérome Cortie for the 3D video. Videos by Omram Bhagchandani and the Kunsthalle Trier.

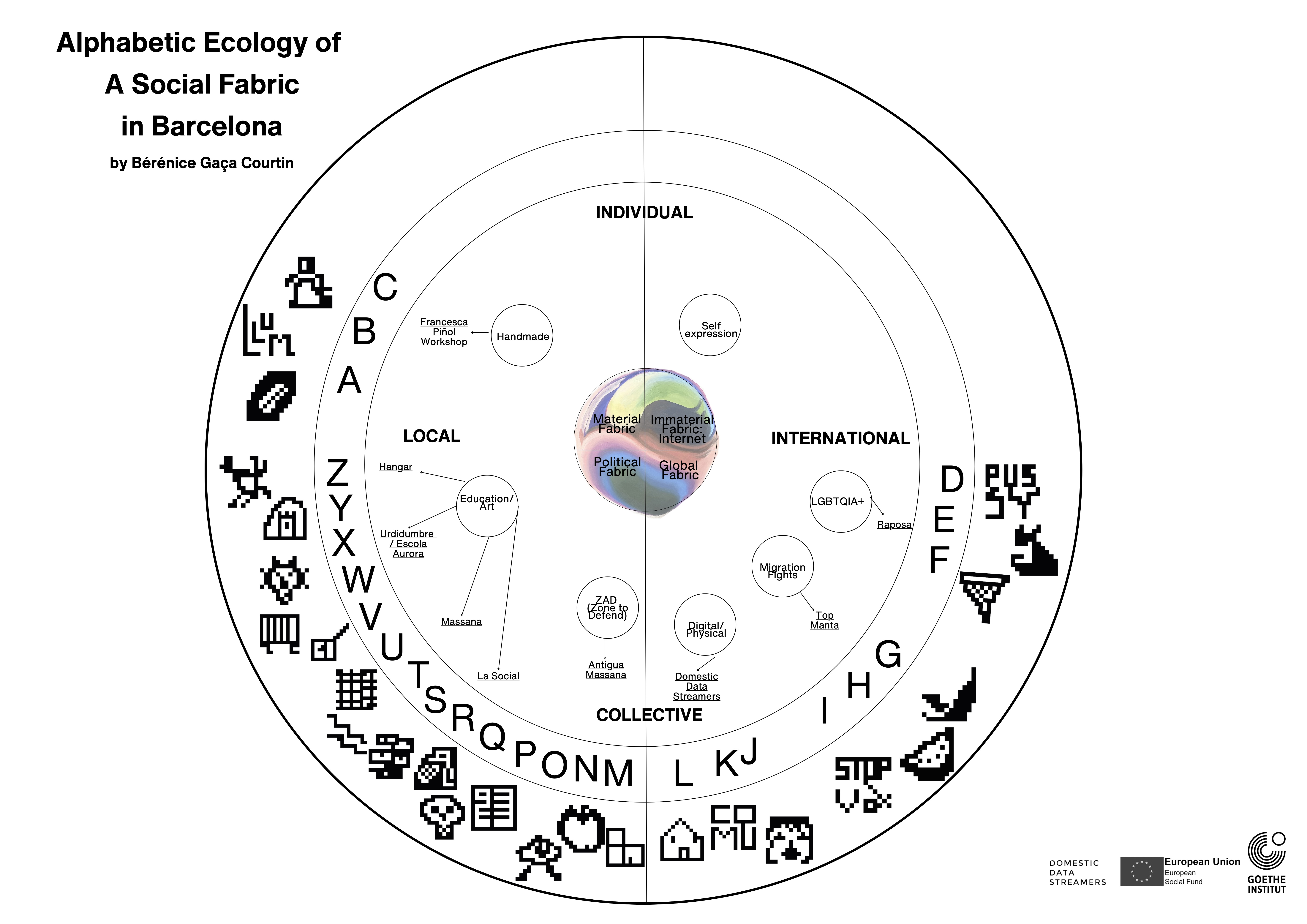

As a way to continue the stories of invented alphabets, I look at how to define them and how to expand them to others. During a residency at Domestic Data Streamers in Barcelona in 2024, about creating new langages, I tried to define a “social web”, to get closer to what I wanted to express.

A social web is formed by social interactions and has a moving shape and structure of interconnected actors. I started playing with what algorithmic structures look like, inspired by how social media are patterned to be shaped by algorithms that seem to control us. The fact of creating a diagram was to enforce our own structural social patterns, being movables, subjectives and spontanious.

I asked people in Barcelona in places that could represent better the subject of social web, to define their social nets. The way that I created this diagram is composed to be changed and it is used to give a certain order to the letters of the alphabet, primatively translated into symbols. I made up the symbols myselft inpired by how they were describing places.

I then wove the alphabet created and made 3D printed representations of the symbols in order to see how the structural binary code of weaving can be represented into 3D.

I’m changing the way I develop these alphabets throughout different contexts. In Trier, at the exhibition about textile and performance, I wanted to explore the museum “Kunsthalle” in all the ways I could think of. I brought my loom to the museum and asked people to draw their own symbols of “places of resistance” from the surroundings, that I would then weave for the final performance.

I then gave the Kunsthalle the piece woven live and I generated a typography out of their symbols, that I could share with who wanted it.

There, I was using a computerised dobby loom (mine is AVL) which is a little bit less complex than the Jacquard. As you cannot control all the threads of the warp, the dobby loom can also be controlled by a program and be connected to a computer.

Demonstration of the weaving software Fiberworks, making symbols to be woven:

This research has demonstrated the multifaceted relationship between textiles and cryptology, revealing their shared structures and historical significance. From encoded quilts to contemporary cryptographic textiles, fabric has served as both a canvas for expression and a tool for secure communication.

My practice is deeply influenced by Sadie Plant, whom I had the good fortune to meet and learn about her exploration of weaving as a cultural, historical and technological act. In her landmark work Zeros + Ones, Plant delves into the tangled history of women, technology and work, tracing the origins of computing back to the loom. 5

Her writings on how weaving prefigures binary code have deeply inspired my work, particularly her assertion that textiles are one of humanity’s earliest forms of complex technology. I see weaving not only as an ancient craft, but also as a precursor to modern computing, a medium that contains within it a kind of coded knowledge.

By drawing connections between the Enigma machine and textile-making, we gain a deeper appreciation for the ways in which material culture and encryption intersect and we question the gender roles tradicionnaly linked to technology. As digital and textile technologies continue to evolve, the future of encrypted fabrics promises new innovations that blend tradition with cutting-edge security techniques.

https://assoagora.fr/cryptographie-et-steganographie/↩︎

https://lejournal.cnrs.fr/articles/steganographie-quand-un-contenu-en-cache-un-autre↩︎

Sadie Plant. Zeros + Ones, Digital Women and the New Technoculture, 1997 p.147↩︎

Elsa Boyer. Turing, p.52↩︎

Sadie Plant. Zeros + Ones, Digital Women and the New Technoculture, 1997.↩︎