Published September 2025 as part of the proceedings of the first Alpaca conference on Algorithmic Patterns in the Creative Arts, according to the Creative Commons Attribution license. Copyright remains with the authors.

doi:10.5281/zenodo.17084410

For the Algorithmic Pattern Festival, I propose a paper presentation that demonstrates and reflects on the artistic method of the unrepeating-repeat—a practice-based framework that explores how subtle variation within repetition can expand algorithmic understanding through embodied shifts of perception and material translation. Rooted in a lifelong love of pattern and a deep curiosity for its cultural, aesthetic, and procedural dimensions, my work aligns with the festival’s celebration of human engagement with pattern as a generative, imaginative force.

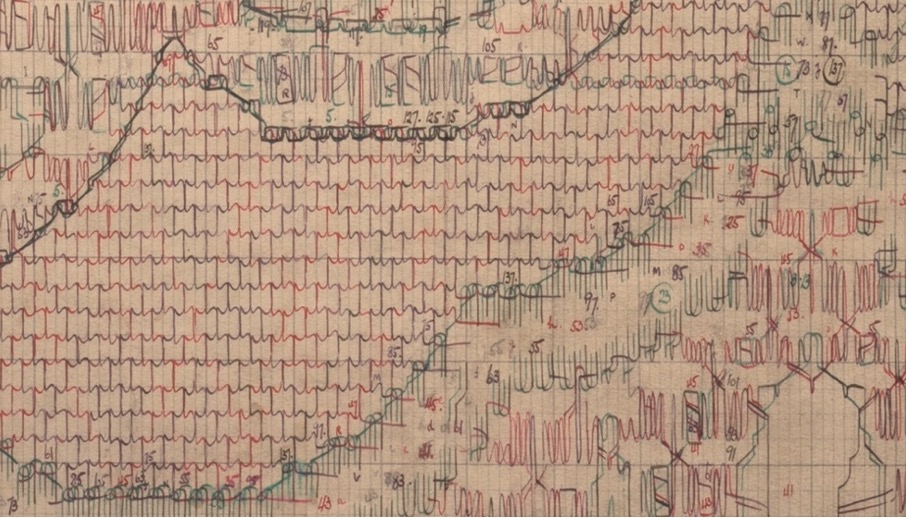

Through a series of artworks developed over three decades of studio practice and refined through recent doctoral enquiry, I will show how the unrepeating-repeat operates as part of a triadic artistic method alongside aspect seeing (Wittgenstein 1953/2010), and intersemiotic translation (Jakobson 1959). Rooted in traditions of textiles, drawing, and text—often realised through site-specific installations—the unrepeating-repeat offers a way of working with pattern that embraces variation as intrinsic and purposeful. It extends the algorithmic glitch as something embedded in both heritage and contemporary contexts—and as a system shaped by curiosity, materiality, and attention. Here, repetition and pattern are not a tool for replication, but a structure to enable re-seeing.

The unrepeating-repeat emerges as both a practical and philosophical approach to making.1 At its core is the recognition that repetition is never wholly identical when enacted through material processes, especially those involving the hand, the body, and time. This is not a flaw or imperfection but rather a generative and encoded condition: small shifts, deviations, or ‘slippages’ within a repeated structure are what allow a viewer to see the other within, to see anew. Rather than static recurrence, the unrepeating-repeat enacts a dynamic cycle in which each iteration invites fresh engagement, perception, and meaning. It is a pattern logic of subtle difference—where variation is embedded not outside the system but within it. This difference is not random but procedural, guided by rules or structures of the unrepeating-repeat that are inherently human, intuitive, specific, and materially responsive.

Through the practice, the unrepeating-repeat disrupts conventional repetition to invite further exploration. By creating a framework in which subtle variations prompt the viewer to reconsider and ‘re-see’, this approach becomes an invitation to encounter each work anew, ultimately encouraging embodied, sustained engagement that enables shifts in perspective. The performative and evolving nature of these works cultivates an active relationship with the viewer—one that is rooted in the nuances of handmade repetition and the tactile sensibilities of textile processes.

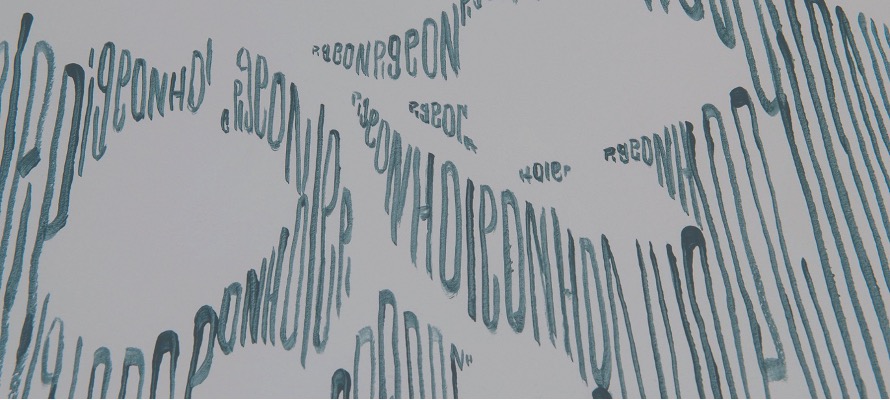

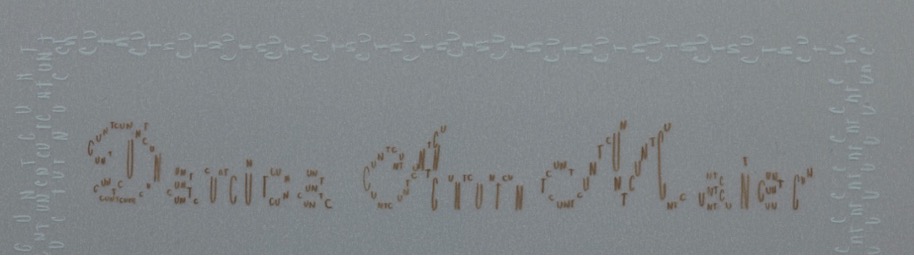

The unrepeating-repeat is a mechanism for activating aspect seeing—embedding variation within repetition to allow the potential for new insight. It is important to understand that experiencing the creative works is not about knowing what is there but about the act of discovery. Drawn from Ludwig Wittgenstein’s (1953) and expanded through contemporary artist and theorist Tina Melzer (Melzer 2022; Melzer and Servaas 2020), aspect seeing refers to the moment in which a viewer perceives an object, image, or situation in a new light—not because the thing itself has changed, but because their perception of it has shifted. This is the familiar experience of the duck-rabbit illusion, in which one visual figure yields two mutually intertangled but exclusive images, oscillating in and out of view. The artistic works aim to cultivate this perceptual condition—not by deceiving the eye, but by embedding layered structures within the work that invite multiple readings. Found through the unrepeat, and accessed through slowness, attention, and close looking, the viewer begins to notice what was hidden in plain sight: an apparent stitch is a drawn line, a line is a letter, a letter is a word.

This perceptual activation is not limited to the pattern but also occurs across semiotic modes—a function articulated through intersemiotic translation. Based on Roman Jakobson’s notion of transmutation across sign systems, intersemiotic translation (1959) in this research operates as a cross-material strategy that translates meaning from textile process into drawing, and text or writing-as-drawing(s). These acts of translation are not neutral transfers but transformative transpositions, where the change in medium also prompts a change in meaning, emphasis, or sensory engagement. A stitched pattern may become a drawn line, which in turn becomes a word; each shift offers a new lens through which to understand the original source. Translation here is not about fidelity, but about resonance and relational meaning. The repeated translation across media acts as another form of the unrepeating-repeat—where each instance is derived from the same source but altered by its context, material, and affordances.

Together, these three elements—the unrepeating-repeat, aspect seeing, and intersemiotic translation—form an interdependent system that structures the creative practice. The unrepeating-repeat directly enables aspect seeing by creating the conditions for shifts in perception, while intersemiotic translation enhances the experience by allowing the viewer to engage with the work through shifting media. Rather than being isolated elements, they operate as overlapping lenses through which both artist and viewer navigate the work. Each element informs and deepens the others: unrepeating-repeat fosters attentive exploration; aspect seeing activates shifts in perception; and intersemiotic translation expands meaning across modes.

The artworks themselves are the starting point from which these ideas emerge, though they are not didactic or illustrative. Instead, they offer environments in which these dynamics can unfold materially and experientially. What may at first appear to be decorative, familiar, or even predictable is gradually revealed as layered, contingent, and unexpected. The viewer’s experience of and with the work is central: they are invited into a process of noticing, of re-seeing, of slowing down and moving closer. This ethos extends beyond the visual into the temporal, spatial, and tactile dimensions of the work—foregrounding not only what is seen but how it is seen, and how that seeing might change. In this way, the research enacts an ethics of attention: a belief that through the careful encounter with repeated yet variant forms, a deeper perception might emerge.

This framework raises questions about how we come to understand pattern and repetition—not just in visual or material terms, but in how they shape our ways of knowing and making sense of things. It invites a rethinking of repetition as a way of perceiving and emboided understanding, where meaning is not fixed but continually unfolding through each encounter. By resisting sameness and insisting on variation within repeat structures, the unrepeating-repeat challenges notions of standardisation, efficiency, and closure that can underpin both artistic and social systems. Instead, it promotes a model of knowing and making that is plural, iterative, and open-ended. The repeated forms do not resolve into a final, total image but remain in motion—always inviting another look, another perspective.

In summary, this research articulates a distinctive method for artistic practice, grounded in the unrepeating-repeat as a structural and conceptual device. Interwoven with aspect seeing and intersemiotic translation, the method offers a dynamic, materially responsive approach to pattern—one that engages algorithmic thinking not through mechanised precision, but through iterative, intuitive procedures shaped by hand, context, and site. Rather than fixed patterns, the creative works function as evolving invitations—asking the viewer not only to look, but to look again. Repetition becomes the engine of variation, and through this process, perceptual, material, and cultural shifts are made possible. Artworks are shared to demonstrate how patterns created through textile logic and vernacular algorithms operate across visual and linguistic modes, generating meaning through subtle divergence rather than exactness. In doing so, the unrepeating-repeat contributes to the festival’s celebration of algorithmic culture as a shared, evolving practice of attention, translation, and transformation.

This framing resonates with philosophical accounts of repetition offered by foundational thinkers such as Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, Søren Kierkegaard, and Henri Bergson. Deleuze’s “difference and repetition” proposes that identity emerges through subtle variation; Derrida’s concept of iterability highlights how repetition always carries difference; Kierkegaard foregrounds repetition as transformation; and Bergson links repetition to duration and memory. While this proposal focuses on artistic and material practices, these philosophical ideas provide a generative conceptual backdrop for understanding the unrepeating-repeat as a mode of perceptual and procedural disruption.↩︎