Published September 2025 as part of the proceedings of the first Alpaca conference on Algorithmic Patterns in the Creative Arts, according to the Creative Commons Attribution license. Copyright remains with the authors.

doi:10.5281/zenodo.17084424

other contributors: Kayla Lu and Jierong

Pattern in music is not only repetition but also transformation. As McLean argues, algorithmic patterns emerge from systematic operations such as substitution, recursion, and interference (McLean 2020). North Indian tabla patterns exemplify this principle. In tabla compositions called kaidas, strokes are repeated and varied according to formal rules, producing complexity through procedural change.

This project asks whether that system of rhythmic logic can be made legible to musicians outside the tradition. Specifically, it explores how tabla strokes might be classified and reinterpreted through a drum kit. The aim is not to teach a drummer how to play tabla in its full traditional sense, but to provide a learning tool that allows percussionists to hear, understand, and respond to tabla’s rhythmic vocabulary. The guiding question is whether machine learning can act as a mediator—translating strokes into another instrument’s language so that a drummer can enter into a call-and-response dialogue with a tabla player.

The contribution of this paper is twofold. First, it develops a classification model that distinguishes twelve common tabla strokes with high accuracy, demonstrating that subtle timbral cues can be captured computationally. Second, it introduces an exploratory generative model that predicts possible continuations of a phrase and maps them to drum kit gestures, drawing inspiration from Paul Westfahl’s tabla-to-drum experiments (Westfahl 2020).

This paper, therefore, outlines a framework: classification as a foundation, prediction as an experiment, and call-and-response improvisation as a direction for future work. By modelling tabla as an algorithmic pattern system and situating machine learning as a translator, we suggest how its rhythmic grammar might travel across traditions, inviting percussionists to engage with it, reply to it, and learn from it in their own idiom.

The tabla is a North Indian percussion instrument with two drums: the smaller, higher-pitched dayan and the larger, bass-rich bayan. Each drum features a black tuning spot (syahi) that enhances harmonic richness. Strokes (or bols) are produced through various techniques, generating a wide range of timbres—from crisp, closed sounds to resonant tones.

Broadly, 12 common tabla strokes can be categorised into three major acoustic groups (Chordia, 2005): - Ringing, bell-like tones: Typically on the dayan, with sharp attack, clear pitch, and long sustain.

For the full classification of individual tabla strokes into their respective acoustic categories:

| Stroke | Category |

|---|---|

| Dha | Resonant Bass |

| Dhin | Resonant Bass |

| Ghe | Resonant Bass |

| Na | Ringing Bell |

| Ta | Ringing Bell |

| Tun | Ringing Bell |

| Tin | Ringing Bell |

| Ti | Closed Crisp |

| Re | Closed Crisp |

| Ki | Closed Crisp |

| T | Closed Crisp |

| Kat | Closed Crisp |

Table 1: Examples of Tabla Strokes and their Classification

Capturing tabla’s nuances, however, is technically demanding. Subtle spectral and temporal differences between strokes mean that rule-based methods fall short in recognising their expressive detail. To address this challenge, the project adopts a data-driven approach: convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for stroke classification and Random Forests for phrase prediction. Inspired by Chordia’s foundational work on tabla recognition (2005), this approach frames machine learning as a translator between musical vocabularies.

The dataset used for classification and generation combines custom-recorded and publicly available material, totalling 8408 sliced tabla strokes from two sources:

Custom Recordings: 2161 slices from full-length performances by Vaibhav Vijay Duratkar.

Public Dataset: 6247 slices from the open-source Kaggle Tabla Taala Dataset.

To ensure high-quality segmentation, all strokes were sliced using Rectified Complex Domain (RCD) onset detection, following the method proposed by Simon Dixon, which was found to most closely approximate manually annotated onsets. Each extracted stroke was manually labelled and saved in the format: strokeLabel_indexNumber.wav: For example: dha_01.wav

All audio files are stereo, recorded at 48 kHz, with 24-bit resolution.

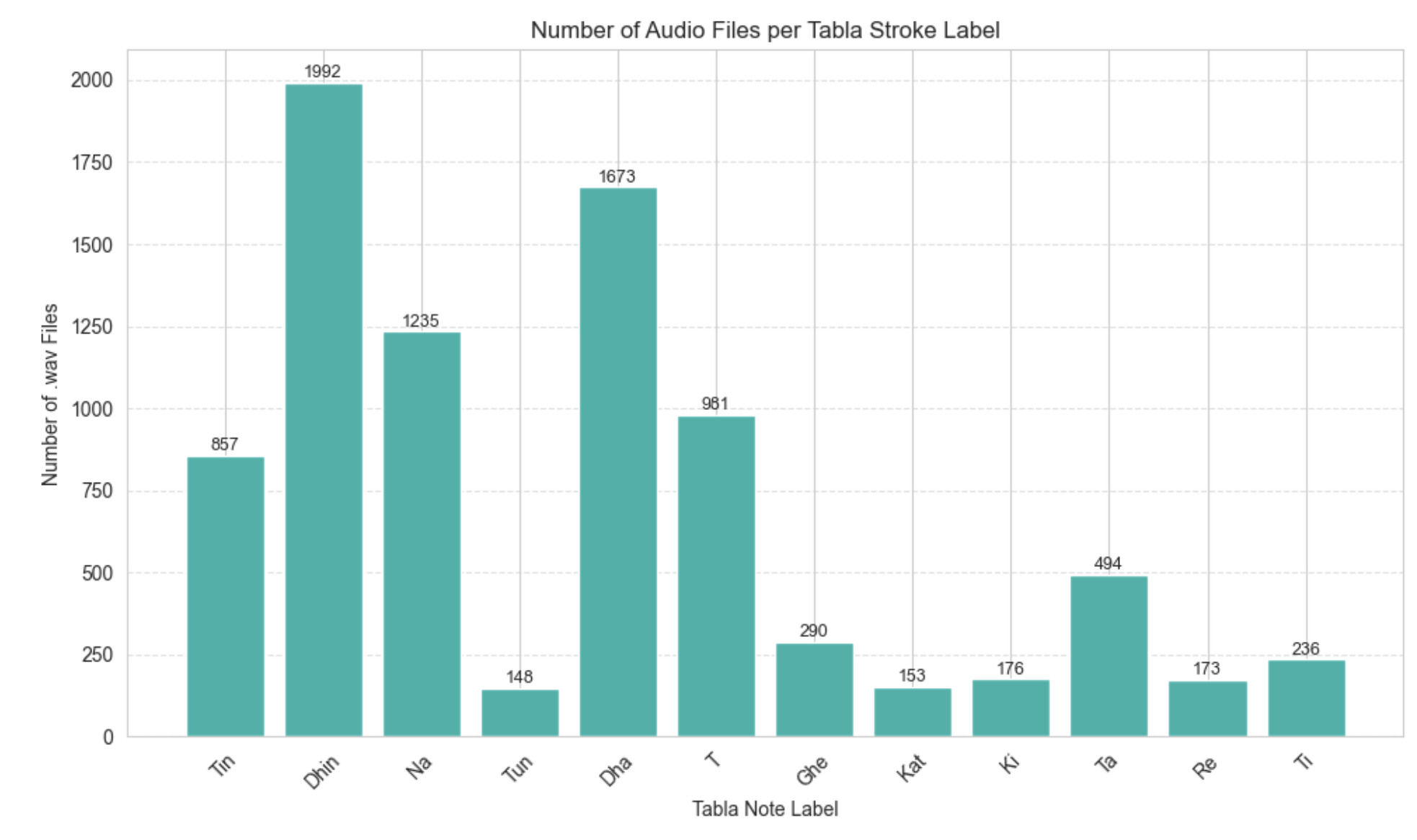

The dataset consists of 12 stroke categories (e.g., Dha, Dhin, Tin, Ghe), but the distribution is imbalanced, as illustrated in Figure 1.

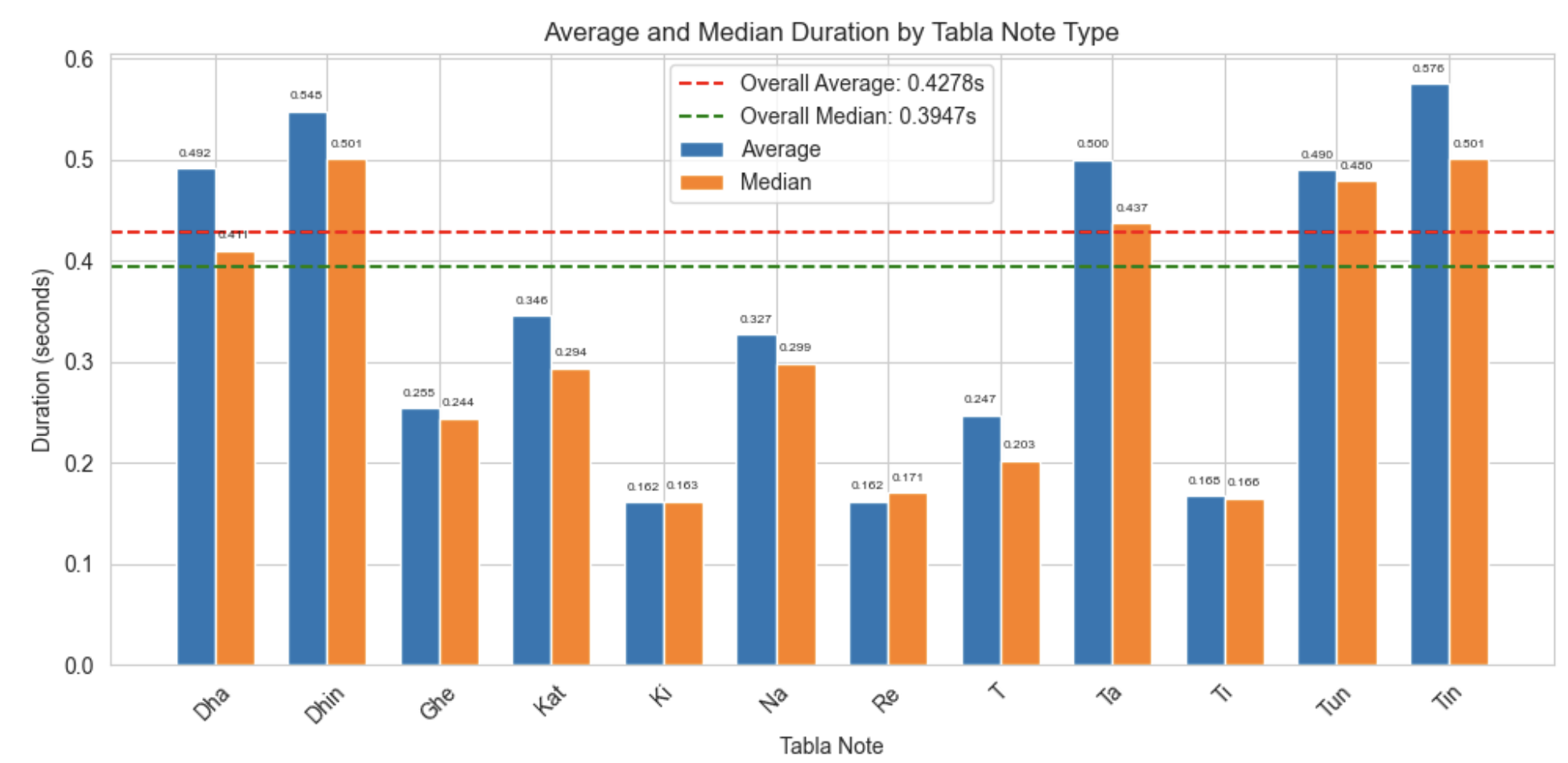

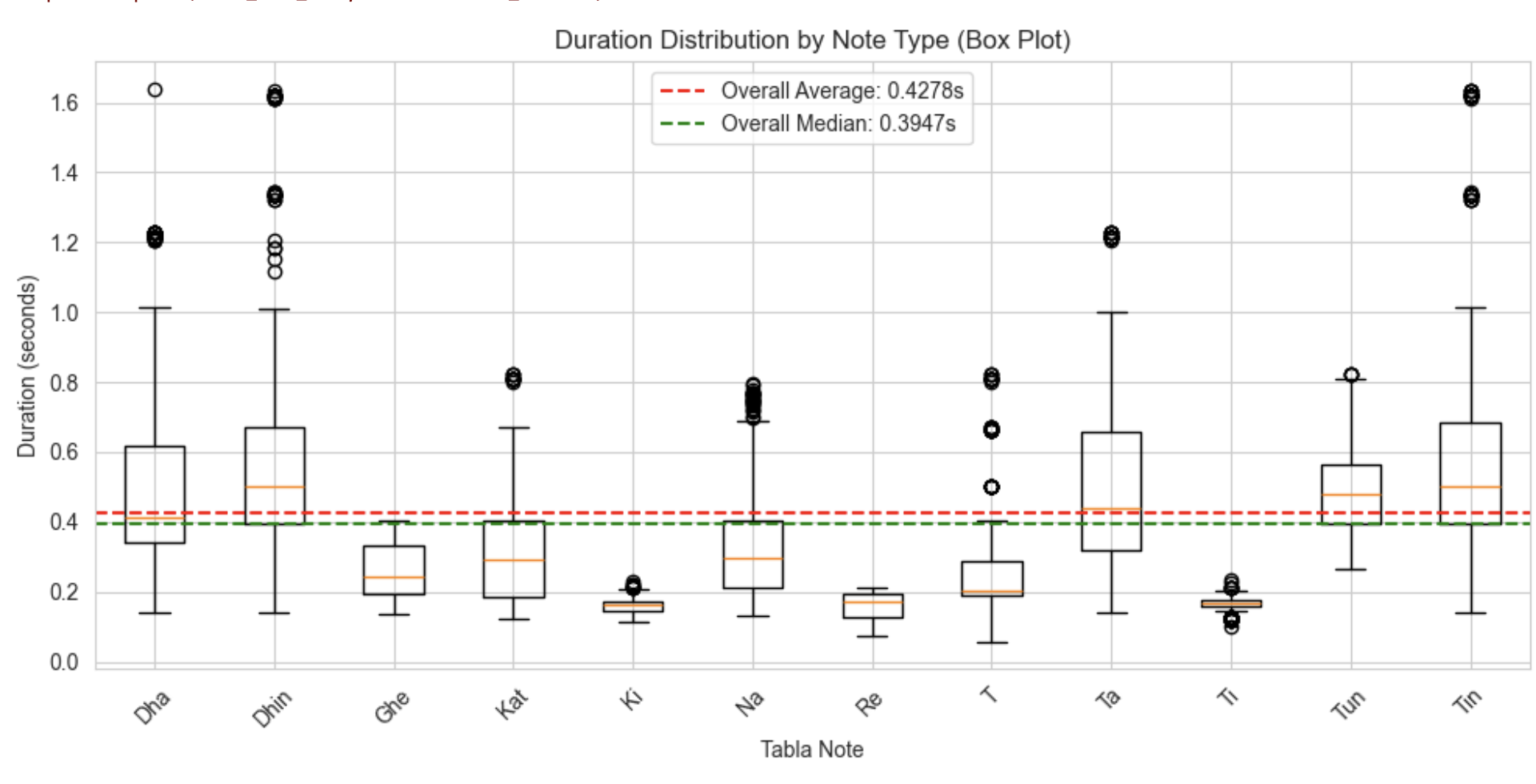

Figure 2: Different length distribution per note “Total_Dataset”.

A preliminary analysis of stroke durations revealed substantial variation in the length of audio samples across different tabla bols (as seen in figure 2 (a) (b)) . This variation is expected, as each stroke possesses a unique temporal profile shaped by its attack, decay, and resonance characteristics. The longest sample (Dha_1623) is 78,592 samples (1.64s), and the shortest (T_326.wav) is 2739 samples (0.06s). To preserve the full temporal structure of each stroke, all audio slices were zero-padded to a uniform length of 78592 samples. Additionally, each sample was amplitude-normalised to ensure consistent scaling and dynamic range across the dataset.

The system consists of a multi-stage pipeline that processes tabla audio to enable symbolic classification and rhythmic response generation::

The most effective feature extraction strategy in this study combined Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs) with Chroma features . MFCCs offer a compact and perceptually meaningful representation of timbre, making them well-suited for capturing the nuanced acoustic textures of tabla strokes. While traditionally associated with pitched instruments, Chroma features—by encoding pitch class intensity over time—proved surprisingly valuable for quasi-pitched tabla strokes such as Na, Tin, and Dha. Though Chroma alone lacks the temporal resolution required for transient-heavy signals, its integration with MFCCs provided a complementary feature space that captures both timbral detail and pitch-related articulation. This combination led to a notable improvement in classification performance, suggesting that the interplay between spectral shape and pitch class intensity is key to modelling the expressive range of tabla strokes.

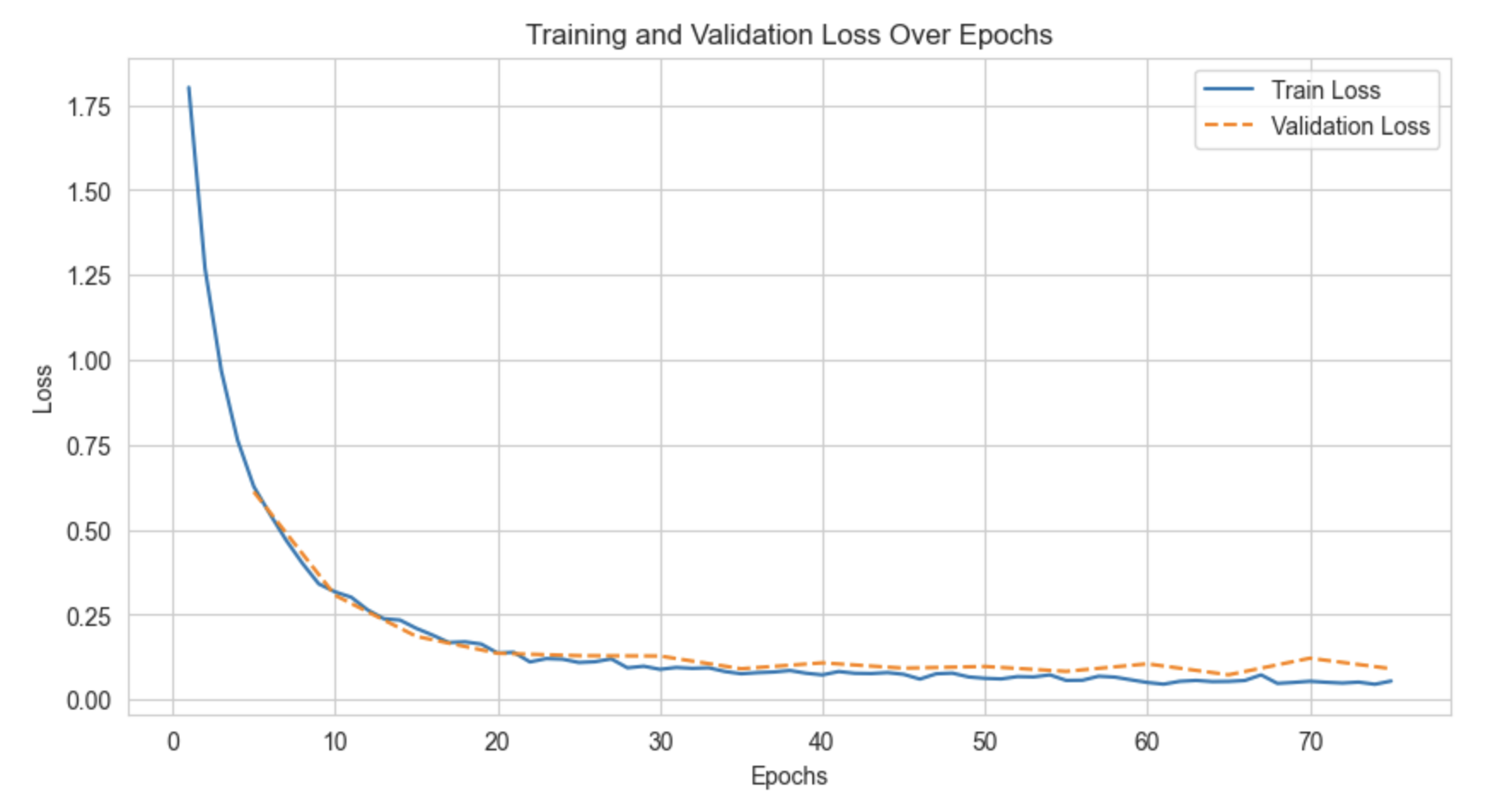

A two-dimensional convolutional neural network (2D-CNN) model was designed to classify individual strokes based on extracted timbral and pitch-related features. The CNN architecture was inspired by models trained on the AudioMNIST dataset, where convolutional layers learn patterns across both time and frequency axes of audio feature representations. The network consists of eight convolutional blocks, each composed of a 2D convolutional layer, batch normalization, and ReLU activation, using a kernel size of 5×5 with padding to maintain feature map dimensions. Global average pooling was applied after the convolutional stack to summarise each feature map into a single scalar value. A final fully connected layer maps the pooled outputs to the number of tabla classes for multi-class prediction using softmax activation. The model was trained on features extracted by combining MFCCs and Chroma vectors. Training was conducted using the cross-entropy loss function and the Adam optimizer, with a learning rate of 0.001, batch size of 50, and for 100 epochs. The implementation was done in PyTorch, with the dataset split into training, validation, and test sets in the ratio 0.8:0.1:0.1.

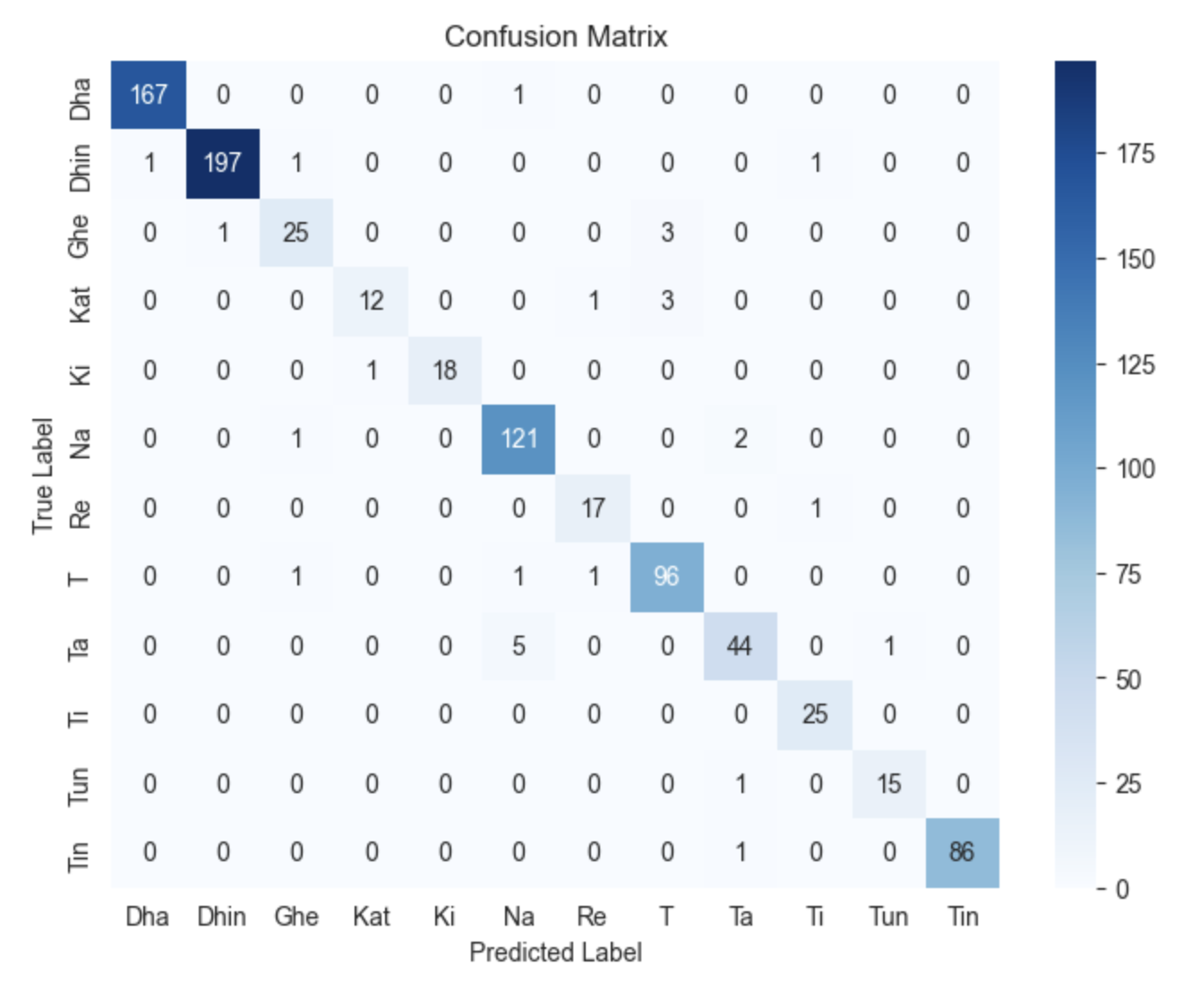

To evaluate the performance of the CNN model, a confusion matrix was computed based on the validation dataset. The matrix (Figure 4) shows that the model achieves near-perfect classification for most tabla strokes, with very few misclassifications. Most mistakes occur between strokes belonging to similar timbral categories, such as resonant bass sounds or ringing open strokes or ghost notes (T). This indicates that the model successfully captures the broad acoustic signatures of tabla notes but occasionally confuses closely related strokes. In general, the model achieved a training loss of 0.0550, a validation loss of 0.0912, and a validation accuracy of 96.77%, demonstrating strong generalisation in unseen data.

| Model 1: CNN Metrics | |

|---|---|

| Training Loss | 0.0550 |

| Validation Loss | 0.0912 |

| Validation Accuracy | 0.9677 |

| Testing Accuracy | 0.9671 |

| Testing Loss | 0.1095 |

Table 2: Performance metrics for CNN Model on Tabla Stroke Classification.

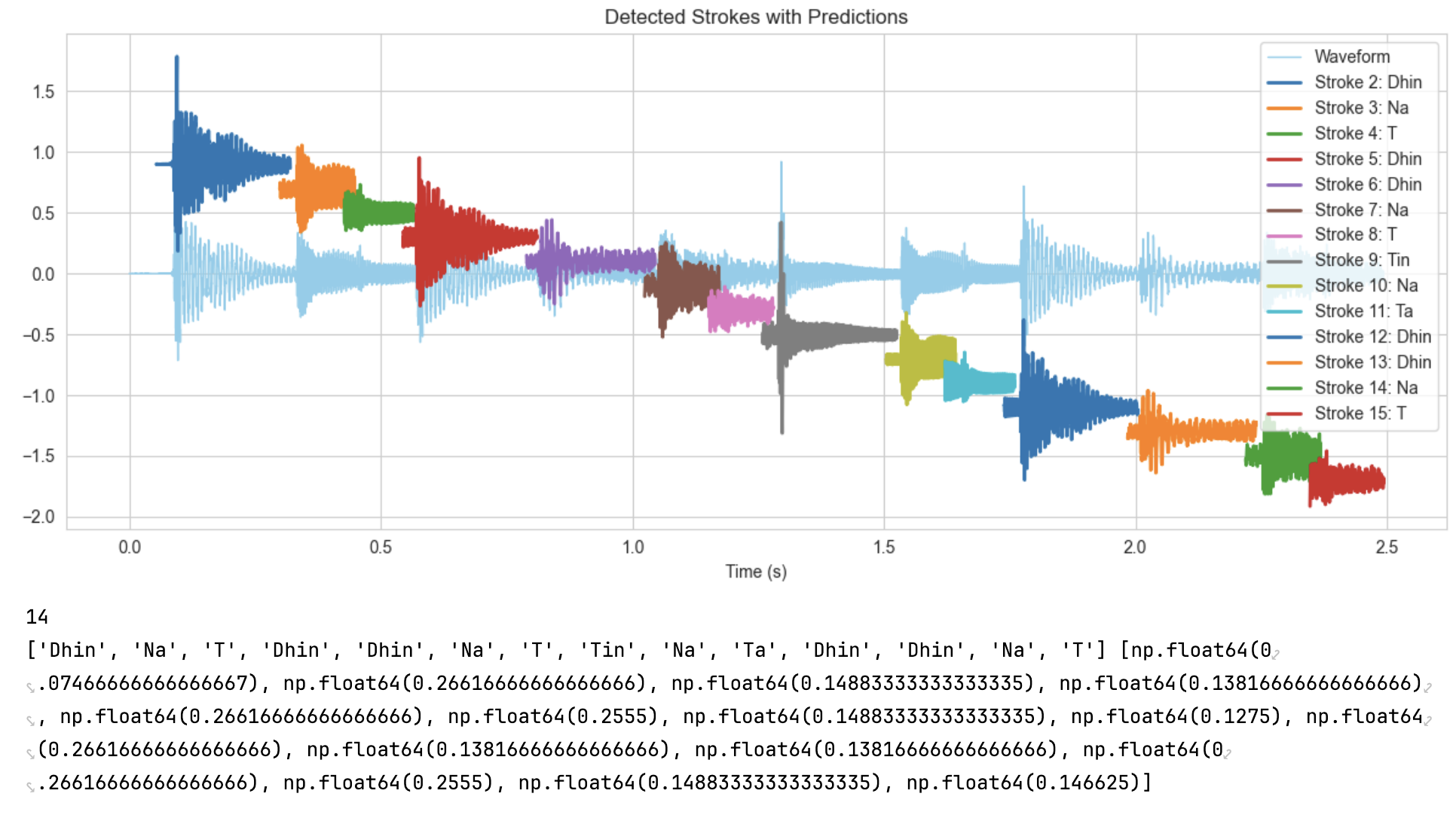

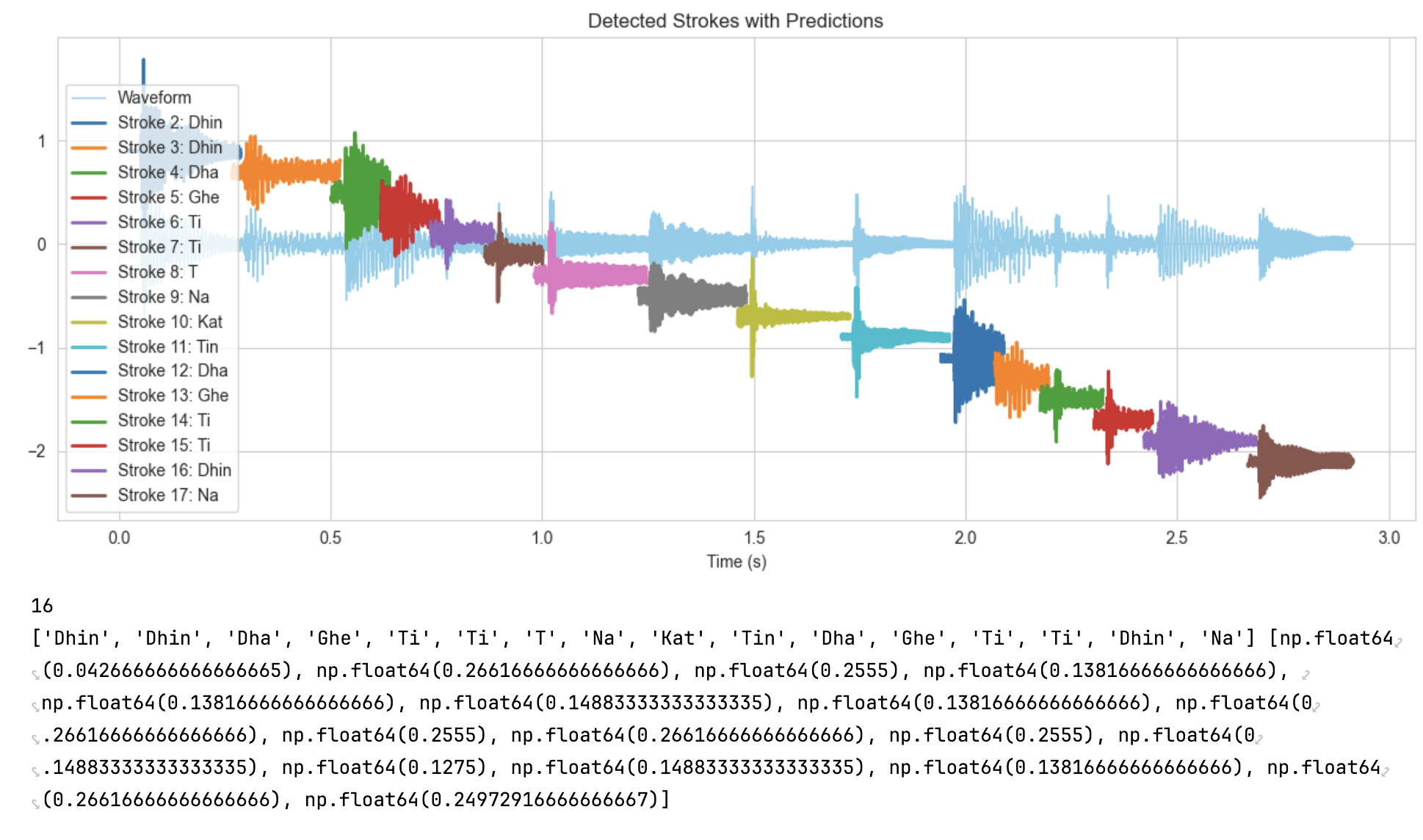

The model was tested on live tabla performances containing real-world phrasing (unlabelled data). Using RCD-based onset detection, individual strokes were sliced from longer performances and classified using the trained model. For instance, in the Jhaptaal pattern from the Unlabelled dataset, predictions were compared to ground truth annotations. Similarly, another example is Ektaal. While the model correctly predicted most strokes, minor errors were again observed between acoustically similar strokes or ghost notes (T). Overall, an accuracy of 86.4% was achieved on previously unseen data from real-world tabla performances, which were originally unlabelled but manually annotated to enable evaluation.

Jhaptaal notes breakdown:

| Actual | Dhin | Na | T | Dhin | Dhin | Na | T | Tin | Na | T | Dhin | Dhin | Na | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | Dhin | Na | T | Dhin | Dhin | Na | T | Tin | Na | Ta | Dhin | Dhin | Na | T |

Ektaal notes breakdown:

| Actual | Dhin | Dhin | Dha | Ghe | Ti | T | Tun | Na | Kat | Ta | Dha | Ghe | Ti | T | Dhin | Na |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | Dhin | Dhin | Dha | Ghe | Ti | Ti | T | Na | Kat | Tin | Dha | Ghe | Ti | Ti | Dhin | Na |

At the heart of this project is an exploration of rhythmic translation, an attempt to bridge the expressive vocabulary of tabla with that of the drum kit. The goal is not to automate accompaniment, but to test whether computational models can enable cross-instrumental understanding, allowing musicians from different percussive traditions to interact with each other.

The generative stage begins once tabla notes are classified by the CNN model. These labelled strokes (e.g., Dha, Tin, Na) are passed into a Random Forest model that predicts possible continuations of a phrase. The model considers the last three strokes and predicts the next one, both the stroke and its duration. Each prediction is then added to the sequence, allowing the process to unfold auto-regressively until a complete phrase is generated. Training was based on eight tabla sequences, each with ten variations, to capture a range of rhythmic possibilities.

While this means that predictions diverge from the training set in roughly three out of ten cases, such divergence is not necessarily a flaw. Instead, it offers a point of creative departure: a little deviation from the sequences can generate new rhythmic ideas, extending the patterns. For duration prediction, the regression model achieved an R^2 score of 0.859, showing that the temporal structure of the strokes is captured with greater consistency.

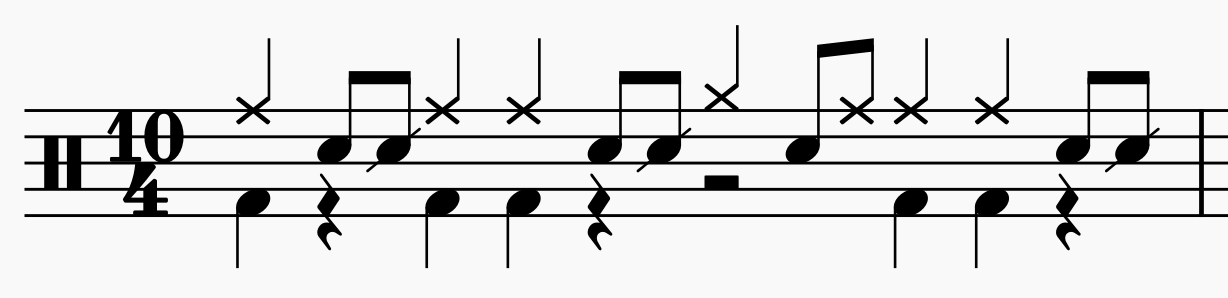

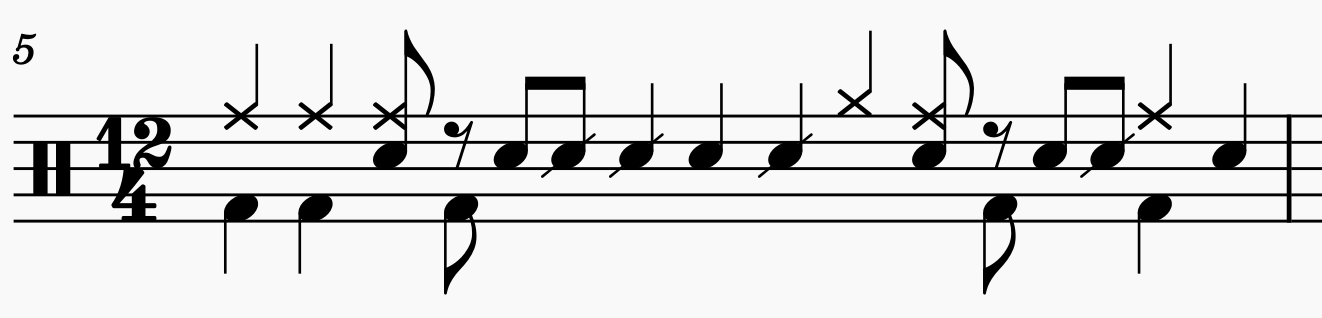

Predicted strokes and durations are then mapped to drum gestures (e.g., Dha -> snare + ride; Tin -> hi-hat). This mapping is inspired by Paul Westfahl’s experiments in tabla-to-drum translation. At this stage, the simplicity of one-to-one mapping allows us to demonstrate that tabla patterns can be symbolically translated and re-expressed on another instrument. More complex mappings like probabilistic, stylistic, or adaptive, are left for future exploration.

In this way, the system functions as a symbolic translator. It offers another musician a parallel line of rhythmic material that can be interpreted in performance. By treating divergence as an opportunity and simplicity as a foundation, the project demonstrates how generative modelling can open new spaces for collaborative improvisation.

Beyond its technical scope, however, the project is also cultural. Can tabla’s rich rhythmic grammar be made legible to a non-tabla player? Can machine learning serve as an interpreter, enabling interaction between musical traditions that do not share a notational system? By generating and translating rhythmic patterns, the system points toward the possibility of cross-cultural improvisation as a shared act of listening and response.

The underlying one-to-one correspondence between tabla and drums is inspired by Paul Westfahl’s interpretation of tabla hits in drums.

Drums output:

One to one translation of tabla notes:

| Tabla | Drums |

|---|---|

| Dha | Snare drum + Ride |

| Dhin | Bass drum + Ride |

| Ghe | Bass drum |

| Na | Snare drum |

| Ta | Ride |

| Tun | Tomb + Ride |

| Tin | Hihat |

| Ti | Snare Drum |

| Re | Snare Drum |

| Ki | Snare Drum |

| T | Snare Drum |

| Kat | Snare Drum |

Run through of the website: https://youtu.be/VlaDEEKVSxI

This project proposes a framework for rethinking tabla not just as an instrument, but as a rhythmic language grounded in algorithmic pattern. Through stroke classification and pattern prediction, we explored how tabla can be interpreted symbolically and re-expressed through the drum kit.

The central question has been whether tabla patterns can be understood and responded to on another instrument. This prototype, combining a CNN classifier and a Random Forest generator, offers one preliminary answer. While its one-to-one mapping is deliberately simple, it demonstrates that rhythmic structures can travel across instruments and still retain communicative energy.

The project, therefore, invites new ways of listening and responding across traditions. It creates a creative space of translation and reinterpretation, but also functions as a learning tool. By translating tabla phrases into a drummer’s vocabulary, the system allows percussionists outside the tradition to engage with its logic, respond through call and response, and begin to understand tabla’s expressive grammar.

Much remains for future work: richer mappings that capture phrase structure and groove, adaptive gestures responsive to timing and articulation, and real-world testing with musicians to assess interpretability and playability. Ultimately, the goal is a bi-directional system in which tabla and drum kit co-shape the conversation. At present, the system produces an almost immediate response, but only at the level of short phrases: a sequence of tabla strokes is played, processed, and then translated into a corresponding drum phrase. This approach aligns with call-and-response practices, where the same rhythmic idea is creatively re-voiced across instruments in succession. What it does not yet achieve is true real-time operation, in which each tabla stroke is classified and translated note by note alongside performance. Developing that capability, stroke-level translation with minimal latency, will be a crucial step toward genuine real-time collaboration.

This work suggests that improvisation across traditions need not erase complexity. Instead, by treating patterns as translatable structures, it allows them to travel, so that others may meet them in their own language, and so that musicians outside the tradition can learn from and play with them.

Westfahl, Paul. Tabla to Drumset Experiment. YouTube video. Posted 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FFdlPUml8q0.

Dixon, Simon. “Onset detection revisited.” Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Digital Audio Effects (DAFx), 2006, pp. 133–137.

Chordia, Parag. “Segmentation and Recognition of Tabla Strokes.” Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Music Information Retrieval (ISMIR), 2005, pp. 107–114.

Patranabis, Anirban, et al. “Categorization of Tablas by Wavelet Analysis.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1601.02489 (2016).

Prasad Upasani. iTablaPro. http://upasani.org/home/itablapro.html

Pedregosa, F., et al. “Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python.” Journal of Machine Learning Research, vol. 12, 2011, pp. 2825–2830. https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.ensemble.RandomForestClassifier.html.

McFee, B., Raffel, C., Liang, D., Ellis, D. P. W., McVicar, M., Battenberg, E., & Nieto, O. (2022). librosa: Audio and music signal analysis in Python (Version 0.11.0) [Computer software]. https://librosa.org/doc/0.11.0/generated/librosa.feature.mfcc.html

McLean, A. (2020). Algorithmic Pattern. Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME), Birmingham, United Kingdom. https://nime.org/proceedings/2020/nime2020_paper50.pdf