Published September 2025 as part of the proceedings of the first Alpaca conference on Algorithmic Patterns in the Creative Arts, according to the Creative Commons Attribution license. Copyright remains with the authors.

doi:10.5281/zenodo.17084430

In this paper, various participants record and reflect on their experience of Pastagang, a radically open jamming group that accidentally emerged in late 2024. Anyone can join pastagang at any time, and there are no entry criteria whatsoever — by reading this, you have already joined. Welcome to pastagang!

In the spirit of the jam, no individual author is responsible for what you are about to read. Instead, it is the natural result of many people editing the same document with no oversight, plan, organization, or discussion. By adopting this practice, the authors have discovered a new sense of belonging and community and now feel closely connected to one another.

Live coding can mean many things1. To many people, it means making software on-the-spot and in-the-moment, often with the goal of performing music or creating visuals.

Pastagang is a phenomenon where live coders use a single collaborative environment as their live coding tool of choice. Whether they’re practising at home, performing at an algorave2, facilitating a workshop, or attending a meetup, a live coder might decide to do it within a single shared space, which anyone can join from anywhere in the world via the internet. This single shared space is known as the pastagang room3.

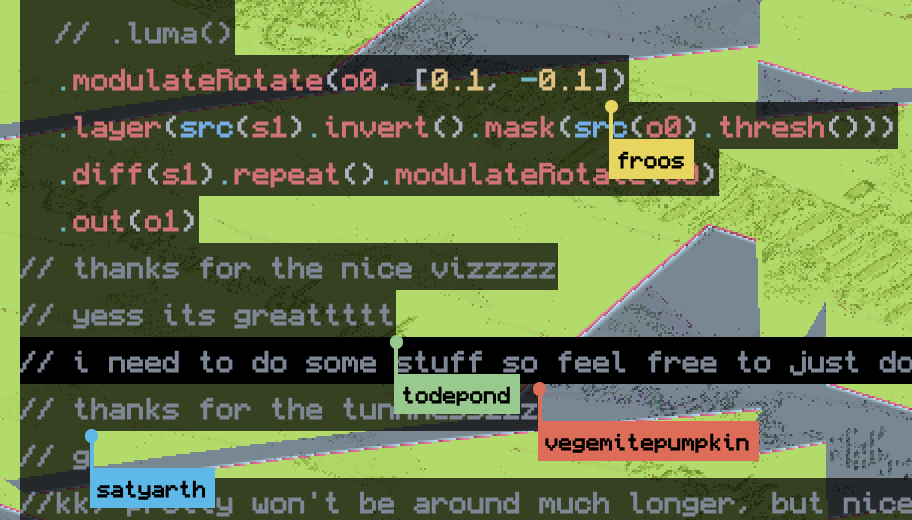

Within the room, members of pastagang write and edit code together on-the-fly to make sounds and visuals and sometimes more (see Figure 1). Anyone can edit any part of the code in the editor, including what other people have written. There is no permission system or authentication. It’s a jam, which means that anyone can add, change, or delete anything they want.

This paper explores personal experiences of pastagang members, focusing on how it helps them to feel free to experiment, to learn, to feel connected, and ultimately, how their participation in the jamming group continues to change them beyond the room itself.

I first discovered pastagang by clicking a link shared by another pastagang member. It brought me to a web page containing a text editor, and I could see that it was multiplayer. I could see other participants’ cursors moving around and typing in real time.

When I first visited the pastagang room, I commented something like, “I’m new, so I’ll just sit here and watch”. Someone else quickly responded with “No, that’s not how it works at all. Join in and make mistakes!”

Multiple times, other members have singled me out and encouraged me to try something new, and have nudged and encouraged me in the right direction with zero judgement.

It can be daunting at first. When you see cursors jumping around on the screen, it can seem like they know exactly what they’re doing. It takes courage to jump in and change a number. Learning that it’s okay to fail is a gradual process. By watching failure happen repeatedly, it becomes easier and easier.

Still, in my first jam, I was admittedly hesitant. I avoided contributing any melodies or rhythms, instead opting for barely audible textures.

After a while, I thought the textures sounded good, so I increased the volume and added more variation. Then I got really confident and added a guitar sound. “Oh no!” — it sounded terrible! Immediately, some friendly cursors floated over to my pane and helped me make it better.

Since then, I’ve contributed drums to another jam. There was one moment where I felt like some of my changes caused a shift in the sounds that someone else was making. I’ve never had that experience before when making music!

Seeing code being developed in a collaborative way has been a transformative experience for me. After not too long, I felt like I could add my own patterns and, with some help from pastagang, I quickly learned how to make them sound how I wanted. I became hooked and now I regularly spend a few hours here and there reading and writing live code with pastagang.

As someone who is new to the live coding world, I find it intimidating to see how much finesse and focus people can perform with during live events. In the pastagang room, I get the chance to look over the shoulder of someone else doing it. I get access to their code in real-time, seeing how they change it and what effect that has. I can copy out code, dissect it, and understand how it works. I can try out some changes and bring them back into the jam. This has allowed me to grow the confidence needed to perform with others.

When you’re live coding solo, you kind of know what’s coming next. But the moment you get a group dynamic going, you start reacting to the unexpected coming at you. It’s generally a fairly slow burn, because you hear a new sound, it sparks your inspiration, then that inspiration gets turned into code and you add your own piece. Then you try to enjoy it for a while. A new spark comes around and the cycle repeats.

These sparks of inspiration can lead to learning how to use new functions, or old functions in new ways, or discovering new samples, or interesting patterns, and so on.

Sometimes, I run out of ideas and I don’t know what to do with my code. My go-to in this scenario is to remove my code altogether and make space (on the screen, as well as in the density of audio and visuals) for someone else to do something, which can reignite the spark in me again. When I’m solo, I need to try to keep a constant stream of new ideas going, which I often find difficult.

The natural highs and lows of activity in the shared room create opportunities for people to be inspired by others jamming, or try out new things when no one else is around. The transition between “real performance” and “just goofing around” gets blurry, and before you know it, you lose an hour to a jam with a bunch of people.

With certain people, I feel that sense of inspiration far more strongly; it reminds me of the concept of a muse4, but it’s usually a two-way relationship, inspiring for both players.

Analogous to the pulsing live body within other forms of performance, the flashing cursor marks the point of decision-making – of consciousness perhaps – within the live programming of code. — Emma Cocker, 20165

Seeing multiple cursors move across the screen making art creates a unique form of unspoken collaboration. Each cursor’s movement represents someone’s creativity and intention, making you part of a larger collective experience. Watching more experienced coders take your initial concepts in a new direction creates a feeling that solo coding cannot match. The nature of adapting your plans to work with others’ contributions mirrors the dynamics of an in-person jamming session. Without explicit communication, these cursors interact with one another and enable a constantly flowing exchange of ideas, leading to unexpected creative directions and fostering a sense of collective creation.

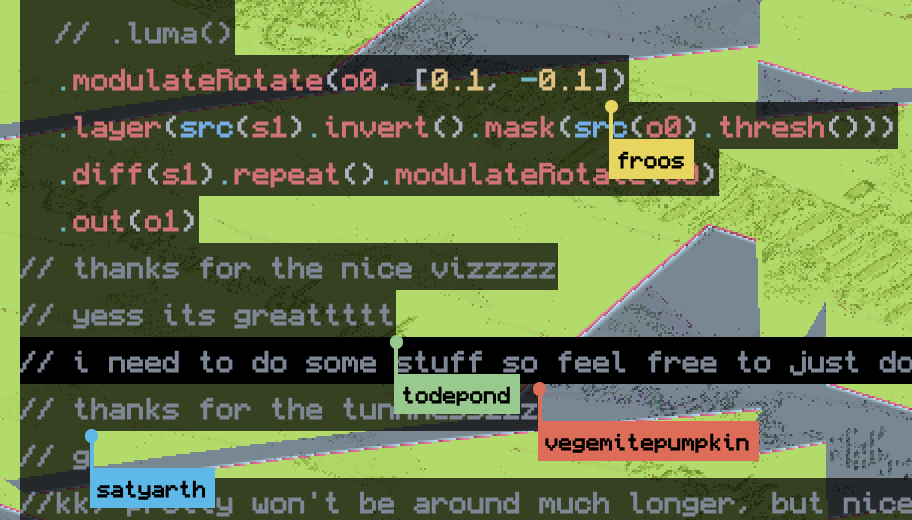

From time to time, “cursorland” comments appear in the jam. These are little ascii-art landscapes like buildings, parks or “chill-zones” for people to place their cursor inside. During working hours, you will sometimes see a few cursors ‘sitting’ in ascii chairs, listening to the music going on (see Figure 2). This creates a kind of co-working environment, where the shared music and visuals are grown while jammers work on their respective non-pastagang projects.

These cursorlands also tend to pop up during bigger live events where not all cursors are trying to actively participate, but may still want to be present in the shared space.

Cursors move with a personality. They edit the code in their own way. Usually they represent a person through their chosen name. Other times they contain emojis or mantras, depending on the weather6. Can we still recognise each other in those moments? Or do we mistake each other for someone else? Which way is better?

I like imagining myself as a little cursor person. I’m gender-neutral and colourful. I duck and weave amongst the code. Sometimes I tweak a little number and we all groove harder. Sometimes I hop next to someone else’s code to write them a little compliment. I really like doing that.

Being cursors in an era where online presences are preconfigured through ‘accounts’ and ‘profiles’ of large corporate platforms creates a kinesthetic subjectivity that aligns with early ideas of cyberfeminist hypertexts. As Carolyn Guertin puts it: “the desire to be other places, to be other people, to always be in flux, to always be in motion wandering with intent.” 7

Like this paper, everything we make as part of the jam gets attributed to “pastagang” rather than any individual(s).

This is partly due to convenience: For any one piece of music or visual, there may have been countless contributors, some anonymous, over a long scattered period. Even if you do hunt down everyone who wrote those individual lines of code, what about those who came before? Those lines of code didn’t come from nowhere: They grew from what was previously there. Sometimes everything gets deleted, and even this can set the stage for the jam that follows. Even a motionless cursor can influence the sounds and sights that take place. Your presence or lack of presence steers the jam.

As an analogy, think of a butterfly. As it flaps its wings, it moves the air around itself, causing tiny whirlwinds. This causes more particles to move, which in turn moves other particles. Eventually, this could cause a tornado to form. Had the butterfly not flapped its wings, the tornado might not have formed at that exact place and time, as the air would have moved differently.

The same effect can happen within pastagang. One cursor movement can completely change the course of the jam.

The jam is also continuous. It has no start and end, so every product of pastagang is a product of everyone who has ever set foot inside it.

For some people, it may seem like a shame to not get individually credited, but in many ways, it is liberating. If something sounds bad, it’s not your fault. It’s pastagang’s fault, so your reputation isn’t on the line. In this way, the jam serves as a tool that removes emotional blockers, in the same way that tools like Arroost aim to8.

Pastagang’s approach to artistic responsibility differs from the typical mindset of algorave:

Algorave musicians don’t pretend their software is being creative, they take responsibility for the music they make, shaping it using whatever means they have. — Algorave website9

In pastagang, musicians relinquish responsibility, but not to the software: It’s the jam that claims your output as its own.

The “death of the author” that goes on in pastagang does share some similarity with the algorave guidelines10 that dissuades against having headliners at events. The focus is on the collective, rather than any individual, emphasised by the hyper-openness of the pastagang jam:

“You could argue that technically the audience is part of the performance with regular algorave as well, through the butterfly effect (mentioned earlier).” “Yeah definitely but I think with pastagang it’s way more explicit?” “It’s part of the paradigm or mindset.” “It seems that way to me, it feels like a very different kind of openness/porousness than regular live coding11.” “Maybe because it has intrinsic connections to chaos theory.” “Yeah and also an explicit rejection of authorship/ownership which in regular live coding is not the case.”

Pastagang takes an approach more reminiscent of the Tiger’s Eye magazine12, a surrealist publication that did not list authors’ names under specific works. Instead, they were all listed on the middle pages of the edition, in a way that individual works could not be routed back to individuals. The goal of this was to place emphasis on the works themselves that ought to stand up on their own regardless of who made them. The same is true in pastagang: The emphasis is on the jam, not the names.

There are also parallels to Exquisite Corpse13, a surrealist game where artists take turns to draw parts of the same picture without being able to see each other’s contributions. The result is a shared activity and piece of art that no single individual is responsible for. The value of such an activity comes from the shared experience, rather than its output.

Long Distance14, an exquisite corpse by Ted Joans, takes collaboration to extreme extents, with 132 artists taking part in its creation from around the world. The piece has been described as a “jam session”15 and values mass collaboration in a way that is echoed by pastagang.

From the early days of improvisational jazz16, to surrealist games, to the long-running WeekendJam17, it is clear that pastagang builds on over a century of jamlike activity that this paper barely touches upon. Future work could explore relating pastagang to these practices to identify links as well as differences.

For me, jamming means high levels of trust, listening, and making space for others. I hope to take these skills into other areas of my life, especially listening.

We are now beginning to explore what it means to bring the jamming mentality outside of the live coding environment.

I was at the bouldering gym today, and I thought “We’re all doing our own thing here, but what if we jammed about it instead?”18. So I just spoke to people, asked what they were working on and if I could try it. Once two of us were doing it, it became much easier to include other people. By the end there were about four strangers, all trying different boulders and collaborating on ideas on how to solve them. It felt wonderful, social and nice, and was a consequence of me inviting collaboration and putting myself with (not in front of) other people.

Jamming can happen anywhere, at any time. It does not require simultaneous presence of other people.

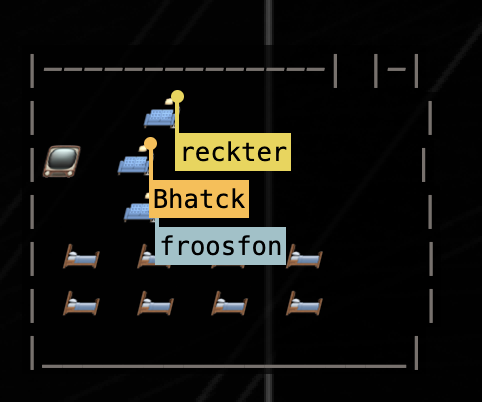

During my stopover at a remote japanese railway station I thought it would be neat if I sampled a local waterfall and played it in the pastagang room (see Figure 3). There was nobody aside from me at the station and only one other cursor present, seemingly inactive. Despite that, I was able to contribute to the collective creation. Later, a train came by, so I sampled it too.

The writing of this paper has also been a jam, with most of it taking place inside an online editor that anyone can join. We have written this paper together, despite many of us being far apart. We invite you to join in too.

Above all else, I love the social aspect of jamming, and that’s something pastagang captures when it’s at its best.

All of that to say that I came for the sound and stayed for the experience.

Blackwell, A. F., Cocker, E., Cox, G., McLean, A., & Magnusson, T. (2022). Live coding: a user’s manual. MIT Press.↩︎

Algorave | About. Retrieved 8 June 2025, from https://algorave.com/about/↩︎

Pastagang. Pastagang. Retrieved 8 June 2025, from https://www.pastagang.cc/↩︎

Muse (person). (2025). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Muse_(person)&oldid=1289878330↩︎

Cocker, E. (2016). Performing thinking in action: the meletē of live coding. International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media, 12(2), 102-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/14794713.2016.1227597↩︎

The pastagang room has its own weather system which determines certain features of the room at that time. For example “palindrome names” changes everyone’s names into palindromes, and “monochrome” makes everything grayscale.↩︎

Guertin, C. (2007). Wanderlust: The Kinesthetic Browser in Cyberfeminist Space. Extensions Journal, vol. 3. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271705091_Wanderlust_The_Kinesthetic_Browser_in_Cyberfeminist_Space↩︎

Wilson, L. (2024). Arroost: Unblocking creation with friends. https://todepond.com/report/arroost↩︎

Algorave | About. Retrieved 8 June 2025, from https://algorave.com/about/↩︎

Algorave guidelines. GitHub. Retrieved 8 June 2025, from https://github.com/Algorave/guidelines/blob/master/README_en.md↩︎

McLean, A., Rohrhuber, J., & Wieser, R. (2023). The Meaning of Live: From Art Without Audience to Programs Without Users. International Conference on Live Coding (ICLC2023), Utrecht, Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7843567↩︎

The Tiger’s eye (1947-1949). Retrieved 8 June 2025, from https://www.ccindex.info/iw/the-tigers-eye/↩︎

Exquisite corpse | MoMA. The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 8 June 2025, from https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/exquisite-corpse↩︎

Ted Joans. (1976). Long Distance [Drawings: Ink, colored ink, crayon, and cut- and-pasted gelatin silver print on folded and perforated computer paper. ‘Skins’: Paper and plastic bags and envelopes with printed papers, ink, string, stickers, tape, and beard trimmings]. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.↩︎

Bruno Marchand. (2019). David Hammons’s “Ted Joans: Exquisite Corpse”—Criticism. E-Flux. Retrieved 8 June 2025, from https://www.e-flux.com/criticism/271759/david-hammons-s-ted-joans-exquisite-corpse↩︎

DiPiero, D. (2022). Contingent Encounters: Improvisation in Music and Everyday Life (p. 260). University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.12066852↩︎

How to: Live-Coding Jams—Th4. Retrieved 8 June 2025, from https://th4music.net/how-to-live-coding-jams.html↩︎

This is a climbing pun.↩︎