Published September 2025 as part of the proceedings of the first Alpaca conference on Algorithmic Patterns in the Creative Arts, according to the Creative Commons Attribution license. Copyright remains with the authors.

doi:10.5281/zenodo.17084434

Olio is a web-based, SVG animation sequencer and code framework that seeks to de-structure and reconfigure rhythmic animations in pursuit of observational knowledge. This paper introduces the tool, its inspirations, and its basic functions.

An olio is a stew, a hodgepodge, a miscellany. Olio is a web-based, SVG animation sequencer and code framework inspired by flasher drums used in Sri Lankan Vesak Pandols.

Figure 1: An example of a flasher drum.1

When I first encountered one of these videos, I was taken by the relationship between the pattern on the drum and its expression as a sequence of animated lights in space. It was like a music box — a satisfying rendering of a cyclical pattern, with its inputs mostly transparent and rhythms legible — but a music box expanded: each connection triggered an entire sequence of effects.

The sequences of animated lights are constructed in roughly the same manner as the SVG compositions I use in my practice, sometimes as base footage for video works and sometimes as the entirety of a live code performance.2 What then might happen if I decomposed these improvisations and separated the sequencing from the animation definition?

What kind of sequences would spatial selection make simple? What performances and changes might result from making the sequencer changeable in real time, in contrast to the fixed patterns of music boxes and flasher drums? How would making the formation and variation of pattern over time apparent change the experience of an audience — or would it at all?

Olio is not only an opportunity to answer the foregoing questions but also a chance to strip down my current practice and interrogate its elements separately.

My work has its roots in live code, particularly visuals, mostly for Codie. In these performances, I code videos live for music that is being made at the same time. The tool I use is La Habra, a Clojurescript-based framework I created in 2017. It uses the same graphics technologies as any website to create layered, long running animations that are updated throughout the course of a show.

Figure 3: Three excerpts from an early Codie performance, showing the rhythmic alteration of elements.

La Habra engages with rhythm and sequence fundamentally. Rhythm is the primary link between the sound and image in Codie’s performances,[Sicchio, Kate, Melody Loveless, and Sarah Groff Hennigh-Palermo,“Alignment of Rhythms in Live Coded Audio-Visual Performance,” Synesthetic Syntax: Seeing Sound / Hearing Vision, Ars Electronica: 2021.][Sicchio, Kate, Melody Loveless, and Sarah Groff Hennigh-Palermo,“Codie Presents,” 2020, 6 min., https://vimeo.com/496209833.] and is attached directly to the animation element in the text interface:

(->>

(gen-shape mint hept) ;; make a mint heptagon

(style {:transform "translate(40vw, 35vh) scale(3)"}) ;; transform it

(style {:mix-blend-mode "color-dodge"}) ;; give it a blend mode to mix with other elements

(draw) ;; create element

(when (nth-frame 3 frame))) ;; rhythmic attachment, appears every three frames In Olio this is removed from the running text code and separated into sequencer boxes.

Likewise, La Habra performances focus on constructing a single running narrative of animations, weaving in and out across time, with the underlying cycles implied to be long, if not infinite; Olio returns inexorably to the top of the sequence every nine segments. While the sequence can be changed as the loop runs, the expression of each composition as a group of nine provides a firm sub-structure.

Olio can therefore be understood as a restricted form of La Habra, devoted to rhythm and pattern orchestration primarily, and to element construction secondarily, as this takes place at one remove.

Olio also takes up the secondary focus of my practice: juxtaposition. A La Habra composition can be understood as a juxtaposition of all its singular elements in time, which is to say, each element has its own time-based expression and the La Habra composition is the result of these being placed together, their time made congruent. In other short sketches, juxtaposition is taken up: in one (5a), by slicing a La Habra composition into smaller steps and rearranging them; in another (5b), by laying these slices out in a grid and playing them together, juxtaposing both time and form. The same is contrasted in a third (5c), where a series of repeated instances displays slightly delayed frames alongside one another.

a: 01010b3-shuffled

Figure 5: Other juxtapositions: shuffled frames; proximate frames; delayed proximate frames.

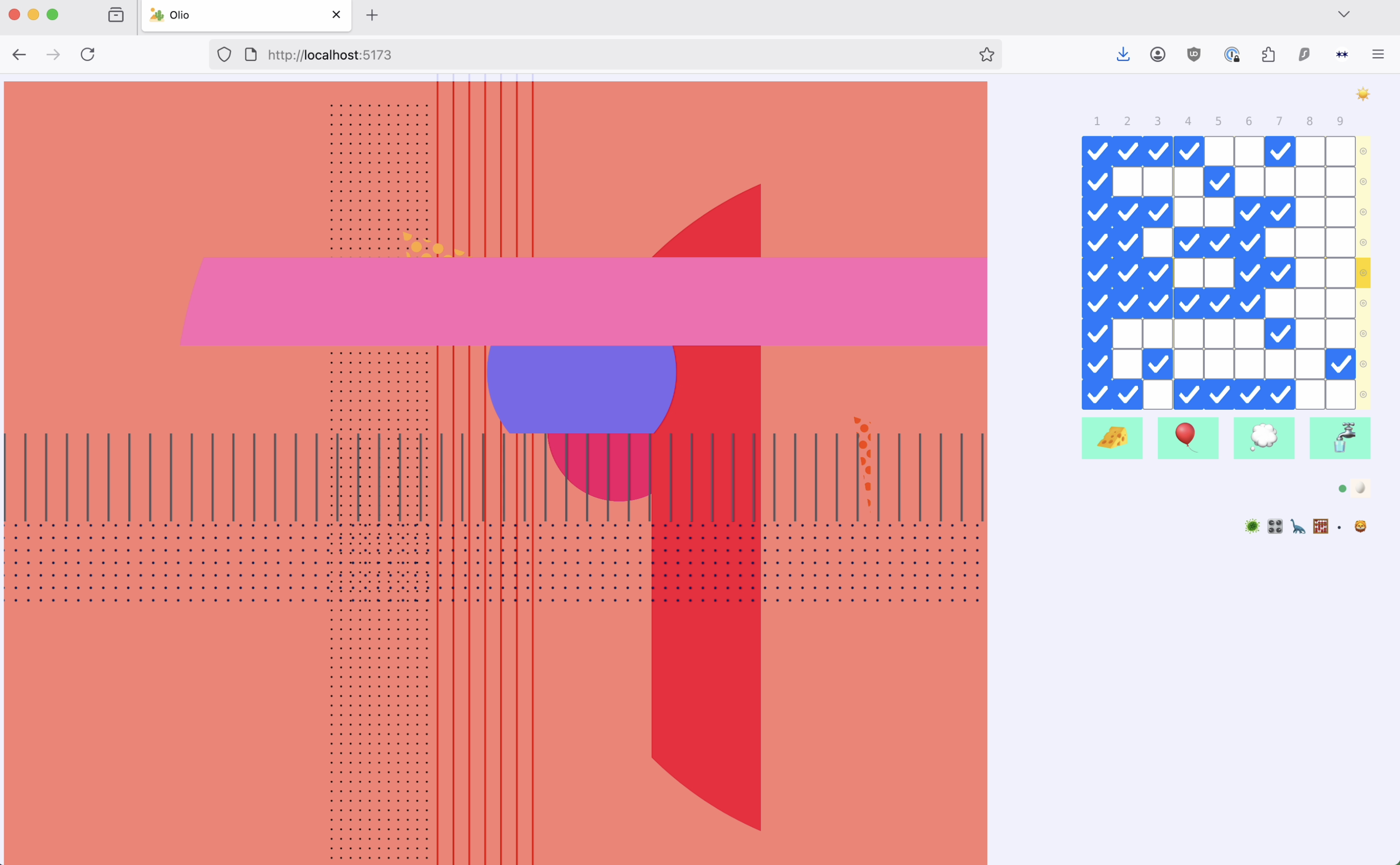

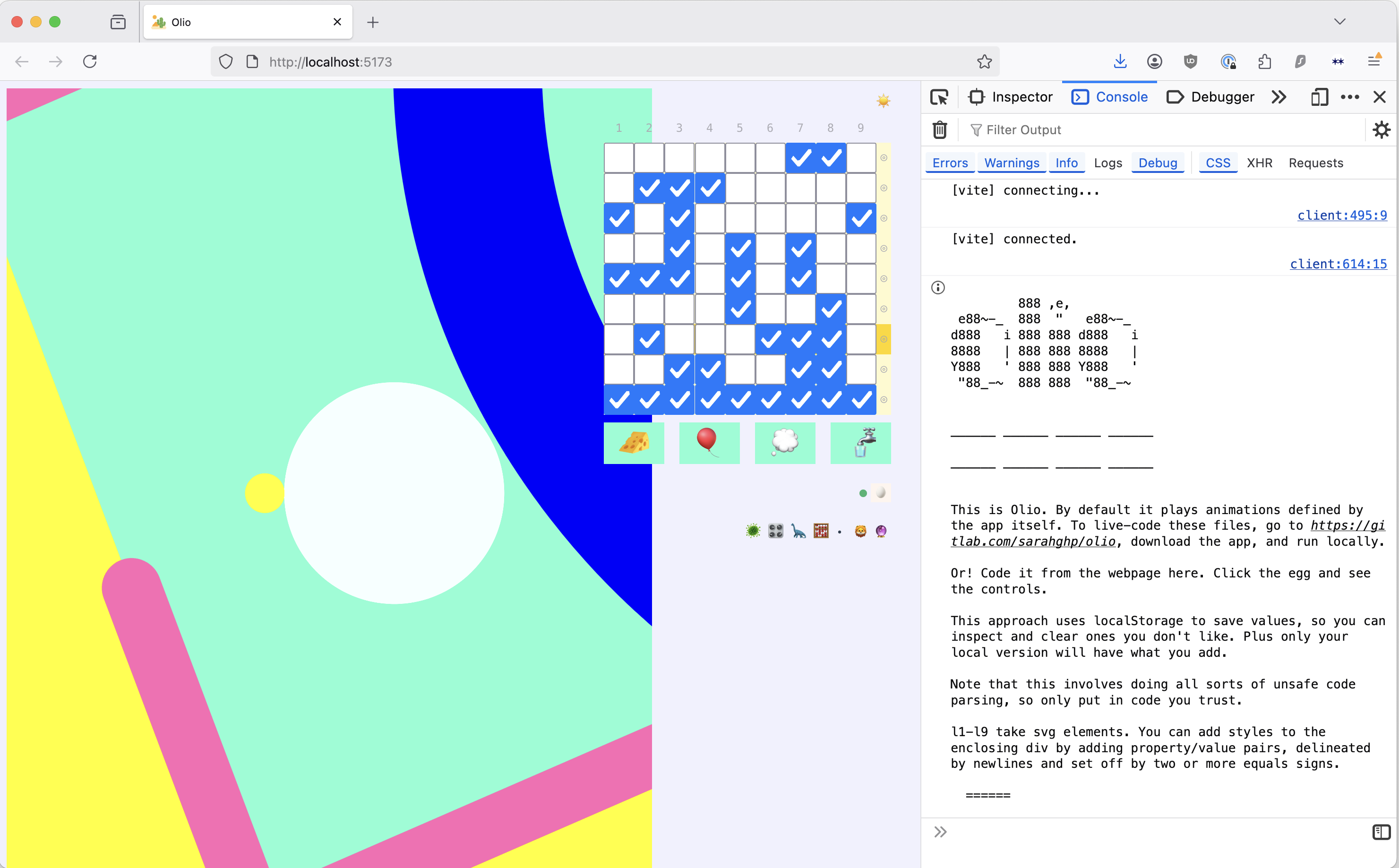

Olio has three main parts, two in the browser and one in the text editor.

In the browser we find Olio’s image space — a canvas if not a

<canvas> — at left and the control section at right.

This can be further broken down into parts: the sequencer, control

buttons, user entry, and the configuration bar, which consists of view

config at left and sound config at right.3

Figure 6: Olio’s basic view, showing user input closed, user input open, and console notes.

Within the sequencer section lies the main sequencer: a grid of 81

checkboxes. The buttons around the sequencer, numbered or indicated with

a ◎, can toggle an entire row or column.

Beneath the sequencer section, control buttons can create a random sequence (primarily for development and debugging), start and stop the player, and clear the screen.

Figure 7: The buttons at the bottom of the sequencer add, start, stop, and clear. The buttons on the frame toggle an entire row or column.

The canvas can represent the same group of nine animations in four

different ways: as a complete composition; as a grid where each element

takes up 1/9 of the space; as horizontal strips; or as a weave of

horizontal and vertical strips. The view icons (🦠🎛️🦕🧮)

select between these views. Keyboard shortcuts are also available and

listed in the console note.

Figure 8: The same images in the four different layout options.

In the last case, the order of vertical strips reverses each frame.

This is because Array.reverse() mutates the data in place

in Javascript, and is a happy accident. It can be disabled by changing

the code to use Array.toReversed(), but it is much less fun

that way.

Originally, the layouts were intended to be confined to only the complete layout and a grid decomposition as counterpoint — however the additional options are equally demonstrative of the dimensions that go into a complete composition, and as such add further avenues for interrogation and exploration.

This is the second happy accident of Olio’s development.

Elements and their associated animations are added in the third section of Olio, the code itself. The tool is structured to use hot reloading, and can therefore be changed while running, although, as noted above, this is is conceived of as a secondary action — or perhaps the first phase of a performance.

As a “restricted La Habra,” Olio still makes use of web technologies, particularly SVG elements and CSS animations and blend modes. This allows for a minimum of extra code for solved problems — no need to reimplement a lerp, for example. I have also currently limited myself to named web colors rather than bring over palettes from La Habra.(The exception to this is the patterned fills described below, which do use La Habra colors.)

Due to Olio’s greater user interface needs, Vue.js in a browser is used, rather than

Clojurescript in an Electron app. In particular, the reactive framework

provided by the Vue options API makes it straightforward to connect the

sequencer grid to the main display through the use of

v-model and to toggle the views.

Each of the nine display groups is represented as its own component. These have access to the path definitions used for regular polygons up to octagons and “squiggles,” irregular line shapes, as well as pattern fills, which are used in La Habra. The latter are small images represented as base-64 encoded strings, which produce the dotted and striped fills.

The display groupings become SVG groups and can contain as many elements as desired.

They are combined in the display file, where the order of drawing can be varied and styles, such as blend modes, are applied. Since each view is currently fed by a single file, the ordering and styles can change across views. This supports relationships in which the 3x3 grid can, for example, be in file order 1–9, but these can be layered differently in the all-together view.

The top-level file toggles between views and adds animations.

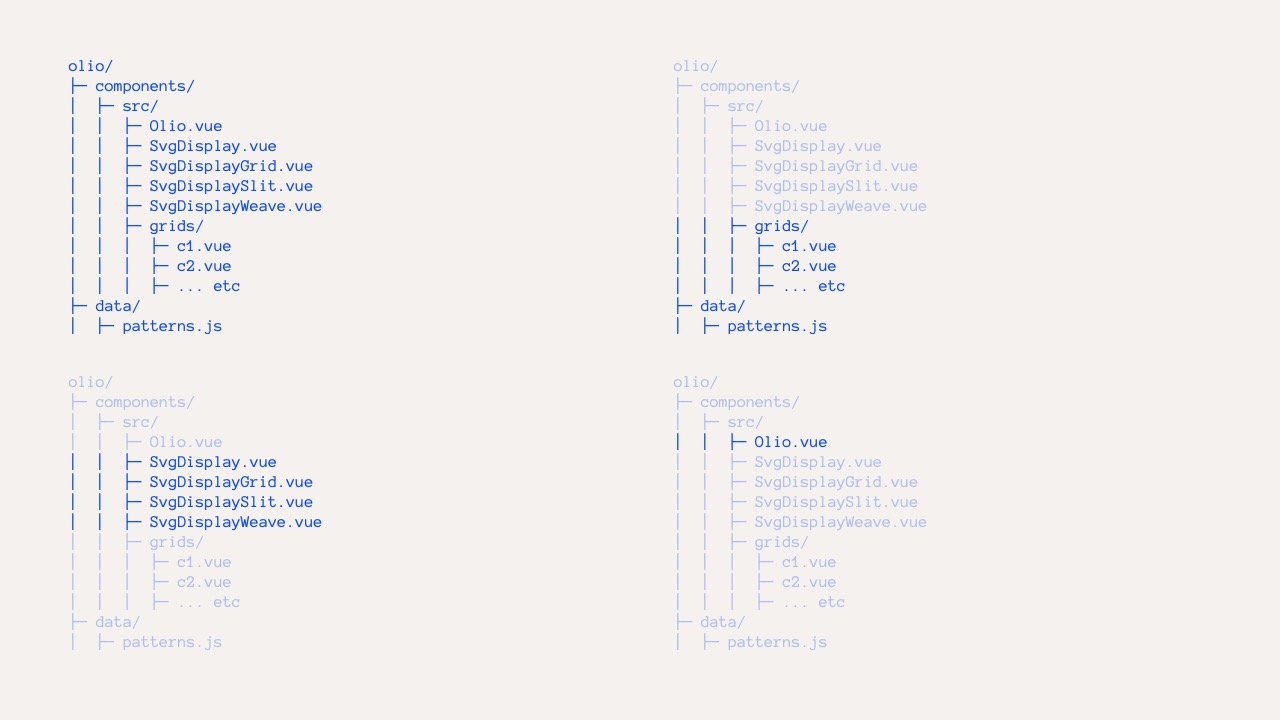

Figure 9: Representations of the file tree highlighting the entire tree, files responsible for the element groups, layout files, and the main orchestrator, respectively.

Animations are defined and toggled using the Web Animations API. Olio allows for components to be either still or totally removed when they are not included in a particular row.

Figure 10: Persistent and removed animated elements in Olio.

Olio makes use of Vite’s hot-reload

capabilities. This means that some state can be reset and animations can

lose track of their reference element. To mitigate this, Olio uses Vue’s

mounted() and unmounted() methods to save a

sequence to localStorage and re-link element references for

a balance between performance and patchability.

Astute readers may have noticed that the first description of Olio in

the browser skipped two options in the config bar — 🦁 and

🔮 — and the strange 🥚 and dot above them.

These capabilities were added to Olio between the initial form of this

paper and publication.

The first two icons trigger the first two sound packs.

🦁 is a series of drones created with the Quord from Sound

Workshop and 🔮 is a series of composable sounds created by

Nancy Drone. In both cases, sounds have been associated with each slot,

or column in the Olio, and are triggered when the animation is

triggered. The drones pack also includes a longer-running background

drone to tie the sounds together.

The strange 🥚 opens the user input section and the dot

indicates whether this input mode is active or whether Olio is drawing

animations from the underlying code, as described in the previous

section. This is toggled by clicking the dot or typing

Ctrl+a.

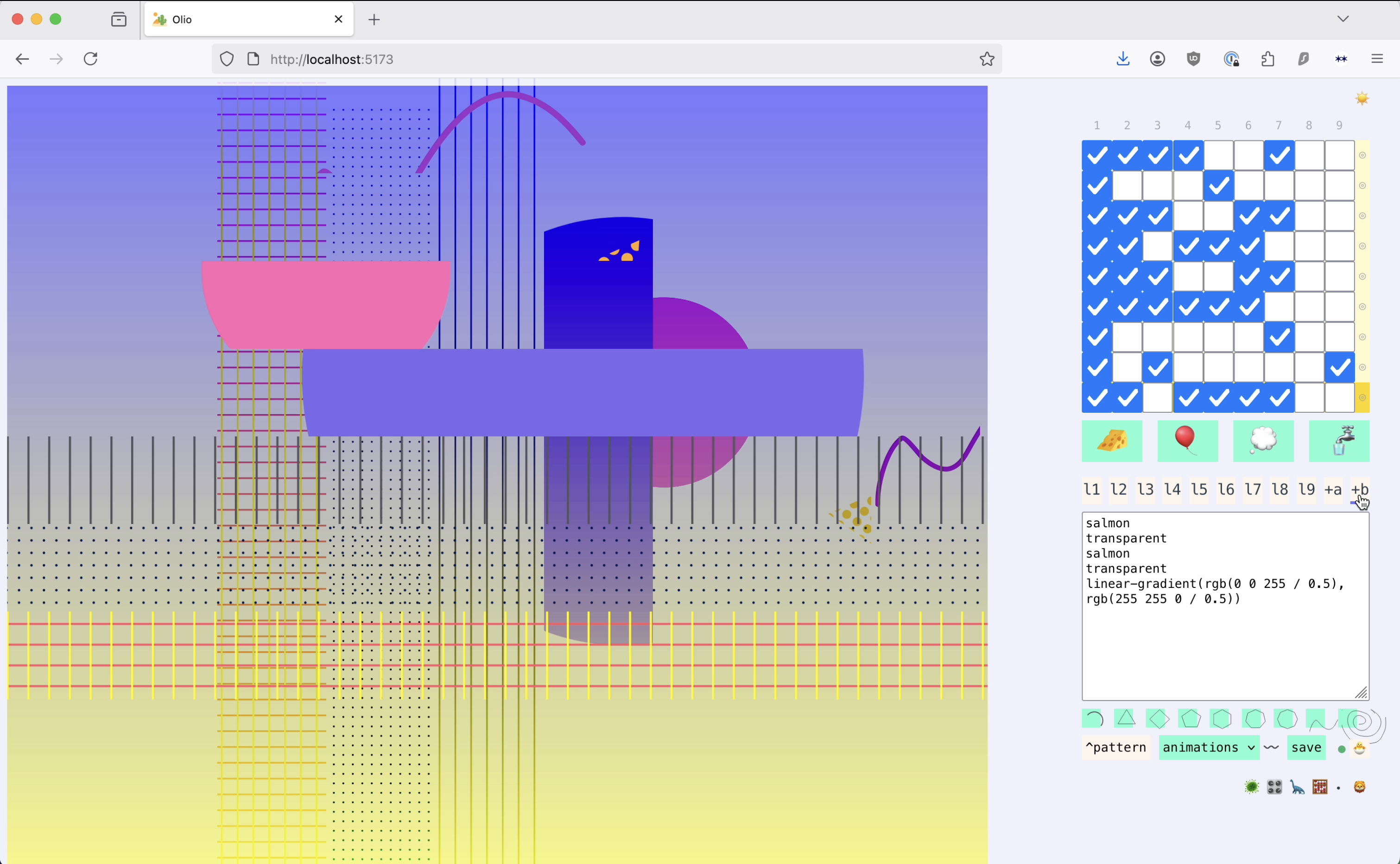

Figure 11: Olio with user input activated and sounds from Nancy Drone

Text boxes l1 though l9 allow the user to

enter elements for the given slot. Styles for the group of elements can

be added by adding property/value pairs, delineated by newlines and set

off by two or more equals signs.

<circle cx="10vw" cy="10vh" r="30" fill="hotpink" />

======

mix-blend-mode: color-burn

transform: scale(10)a+ is the input tab for adding animations, which will

then be selectable in the animations dropdown. b+ is for

adding background colors. Since this is a web project, all web colors

can be used for elements and backgrounds: named HTML colors, hex or any

other CSS color-space specified colors, as well as linear gradients.

Figure 12: Adding a new element with path and pattern injection, wrapper styles, new animation and background colors.

The ^pattern button injects code for specifying

patterned fills, and the small squiggle next to the animation dropdown

indicates whether an element will appear still on the screen when it is

not activated in the sequencer. Finally, the icons with paths on them,

like triangles and squiggles, inject the code for these paths into the

text-entry box.

The save buttons saves the entered code, and can also be

triggered by Cmd+Enter.

Additions and selections made in this mode are saved to user’s

browsers using the localStorage interface. This means users

may practice and save their elements, but they remain local to the

user’s browser, and therefore do not exist elsewhere.

The first video shows Olio v1 in effect, from element creation through live sequencing. The second shows Olio as an input to a more complex video animation.

When this paper was first conceived, the obvious next steps were adding sounds and the ability to add elements from the browser itself. The first pass at these functions has now taken place, but they remain the site for further exploration.

Olio currently has two sound packages. I aim to have four or five in the end, provided by different musicians.

Beyond these, it might be interesting in the future to make it easier

for users to add their own sound packages, by making a form that allows

users to save files to localStorage and choose a toggle

icon.

For the more complex element user input, the next steps are less

clear cut. Many questions circle around how much and what kinds of

shorthand should be made available. It is clear that a path

element should be injected, because no one is likely to remember that to

draw an arc one must write:

d="M 0 0 A 45 45, 0, 1, 1, 90 10"much less that a cute squiggle is rendered:

d="M 20.953369 417.538483 L 20.953369 407.721741 C 20.953369 350.180725 48.549683 242.937134 96.530518 207.867279 C 107.957031 199.515869 151.341309 260.243164 161.959717 269.533752 C 221.439575 321.575195 266.966064 319.998749 304.296875 250.99231 C 351.175659 164.333771 449.306519 -1.531616 566.616821 23.046509 C 633.865234 37.136414 681.342896 86.097595 722.294067 137.206757"Should, however, linear gradient code, which can currently be copied from the console, get its own button, or is it better for this to be a part of a performer’s skill toolbox?

Put more generally: what is it reasonable to expect a user to know? The elements are, at bottom, SVG elements, and live coding them does imply growing one’s understanding. Is the ramp of the tool, from live-sequencing included elements through to writing animations on the fly, open enough at the beginner end to balance out the advanced use cases requiring a deeper understanding of the web?

Would it improve the balance to let users upload “image packs” with

elements and animations into localStorage along with

sounds?

These are some of the paths user input could travel.

As well as sharing inputs, there are possibilities for further

affordances around sharing outputs. Since memory is now limited to

localStorage, people are not able to share things they have

made on their machines directly with others.

It might be worth encoding information about a given configuration to the URL so it can be shared. In particular, it could be interesting to slowly create a sharable series of olios that contain either the same sounds and different images — or the inverse — to facilitate observations that are rooted in small variations.

Within my practice, performance is also a research method, clarifying the use and interpretation of the framework under pressure. I look forward to using Olio in some performances in the future — as an alternative and not a replacement to La Habra. I hope to observe what audiences respond to and take away from a decomposed performance.

Running workshops to introduce other visual artists and live coders to Olio could help guide the next steps of interface development beyond my personal performance needs.

In the introduction, I listed a few of the questions I hope Olio will help me answer. While it is still early days and these answers are tentative, this is my report so far.

What then might happen if I decomposed these improvisations and separated the sequencing from the animation definition?

Using the first mode of Olio, where elements could only be added through code, I found the process contradictory to the didactic goal of adding elements and using the different visualizations to assemble and then reveal the complete composition. That is, how could I expect an audience to understand the pieces if they were not always in front of them? I also discovered that toggling between the code and the images prevented me from building fully on the existing elements.

Separating item definition and sequencing then not only made composition comprehension difficult for others, it made it difficult for me as well. This reflects an ongoing conundrum I face with live-code visuals more broadly, in which the tension of wanting audiences to look at images conflicts with the desire for them to look at code. Unlike performed sound, where two senses are being used, foregrounding the code diminishes the art, and vice versa.

This was operating in the mode I learned from La Habra, and the difficulty of operating as usual sent me looking for a solution: I added the browser-based input tools fairly quickly.

And yet, to better try to answer this question rather than only retreat to safety, I have spent some time since improvising in the original mode — without changing code at all. This can be uncomfortable; to create space between steps, a certain restraint is necessary. The output sequence is therefore often spare, and as it works best without sound, it is even sparer. This mode rewards sustained attention to the image pattern. With little change to the sequence after setup, the unwavering repetition of the nine steps provides ample opportunity to observe detail through the juxtaposition. Boredom or feelings of confinement can be relieved by looking more closely, and this then allows for the observation of felicitous interactions between elements.

It remains unclear if this willingness to be uncomfortable should be brought to a performance or limited to personal exploration.

What performances and changes might result from making the sequencer changeable in real time, in contrast to the fixed patterns of music boxes and flasher drums?

Because music boxes and flasher drums cannot be changed once set, the performance must be spectacular to offset the repetition — large or highly refined. Olio allows for performances that are more spontaneous and less perfect, which is to say: weirder and more surprising.

In common with its forebears, the limited slots in Olio encourage thinking in detail not only about which groups combine well, but about which items are in a single group.

Both of the aspects combined led to the felicitous discovery of the moving-grid effect that is created when a foreground item and background item are animated together.

What kind of sequences would spatial selection make simple?

Spatial selection, which is to say, using the sequencer grid to select items — instead of assigning items individually to a repeating sequence of frames, as with La Habra — is a source of many traps. The temptation is to make a pleasing pattern on the grid, an X, a cross, steps, but, as I have discovered when using the random button, the most pleasing compositions do not usually follow this pattern.

This is an opportunity to discover how to move from the informative and didactic to the pleasing.

How would making the formation and variation of pattern over time apparent change the experience of an audience — or would it at all?

As the performance accompanying the presentation of this paper will be the first performance, this question remains unanswered. One thing that I have discovered along these lines, however, is that I have a great fear of a performance that is too static, and it is this fear that Olio forces me to face with its reduced surface area and tendency towards sparseness. I will have to be brave.

Kasthuri, Jeevan, “Flasher Drum for Thorana,” June 9, 2018, YouTube, 4 min., 57 sec., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sTnduLOh6wA.↩︎

See Groff Hennigh-Palermo, Sarah, “On Continuity: Video Synthesis and Live Code Visuals,” International Conference on Live Coding, Barcelona, Spain (2025), http://salad.sarahghp.com/continuity-sarahghp.pdf, and Groff Hennigh-Palermo, Sarah, “Eurorack & Live Coding Guest Tutorial with Sarah GHP!” https://vdmx.vidvox.net/tutorials/guest-tutorial-with-sarah-ghp for setup descriptions.↩︎

Readers may wonder about the connection between the emojis and the buttons’ actions. What connections exist are tenuous and personal; the images were chosen obliquely to give the interface a sense of textless play. Emojis are being used because they are the most accessible images for web development, although they could be changed in the future to give the interface more of a personal aesthetic. At the same time, use of emojis also imparts an open web feel that may be worth preserving.↩︎